Why is Tonga so obese

Obesity in the Pacific

Overview of the causes for and prevalence of obesity in the Pacific

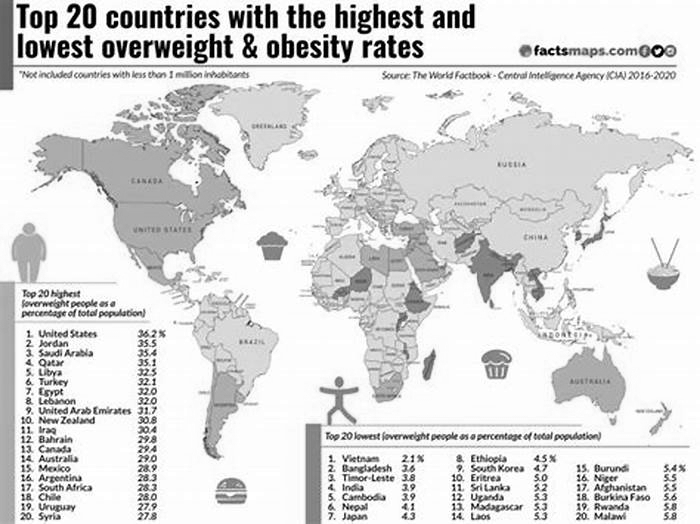

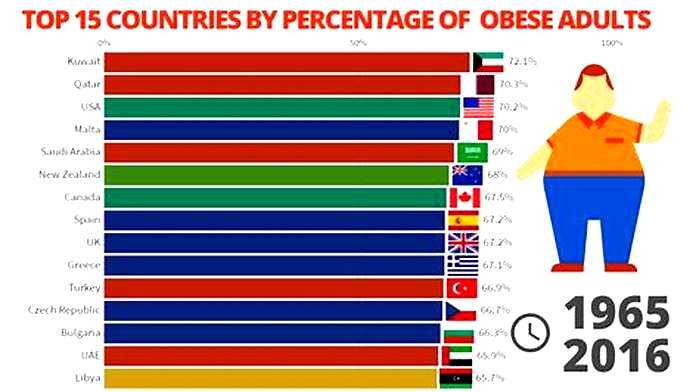

Pacific island nations and associated states make up the top seven on a 2007 list of heaviest countries, and eight of the top ten. In all these cases, more than 70% of citizens aged 15 and over are obese.[1] A mitigating argument is that the BMI measures used to appraise obesity in Caucasian bodies may need to be adjusted for appraising obesity in Polynesian bodies, which typically have larger bone and muscle mass than Caucasian bodies[citation needed]; however, this would not account for the drastically higher rates of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes among these same islanders.[2][3][4]

Overweight populations[edit]

Obese populations[5][edit]

Nations[edit]

Obesity is seen as a sign of wealth in Nauru.[6] 31% of Nauruans are diabetic.[7] This rate is as high as 45% among the 5564-year-old age group .[6]

Life expectancy in Tonga is 71 and has been steadily rising since the 1960s.[8] Up to 40% of the population is said to have type 2 diabetes.[9] Tongan Royal Tufahau Tupou IV, who died in 2006, holds the Guinness World Record for being the heaviest-ever monarch with a weight of 200 kilograms (440lb).[9]

In Fiji, strokes used to be rare in people under 70. Now, doctors report that they have become common amongst patients in their 20s and 30s.[10] Research done on globalization's impact on health indicates that the rise in average BMI in Fiji correlates with the increase in imports of processed food.[11] Dr Temo K Waqanivalu, a Fijian representative for WHO, attributes health problems in his country to the replacement of traditional foods by more glamorous imported foods.[12]

Marshall Islands[edit]

In the Marshall Islands in 2008, there were 2000 cases of diabetes out of a population of 53,000.[10] Diabetes prevalence in adults in the Marshall Islands in 2011 was 21.8%.[13] A survey done in the Marshall Islands revealed that the percentage of the total population considered overweight or obese was 62.5%.[14]

Cook Islands[edit]

The Cook Islands comprises fifteen small islands and has a local population of about 10,000 people. In the Cook Islands, meals and feasts exemplify a level of community. Food habits play a role in maintaining social status and hierarchy.[15]

The arrival of fast food restaurants and other contemporary food items on the islands are one of the issues responsible for the obesity in Samoa. The earliest photographs of Samoans provide visual proof of the native population's natural physique before the introduction of processed foods by Western society. The natural lifestyle of physically labouring to provide for natural foods and building shelters and communities gave way to modern conveniences like drive through restaurants, motorised vehicles, air travel, wireless communications, and pharmaceutical and recreational drugs. The development of modern society, although advanced with technologies, has also made it easy for many to live an unhealthy lifestyle, therefore leading to obesity.

Colonial history and social change[edit]

In the early twentieth century, external people visiting the islands such as missionaries and colonial visitors to the Pacific Islands influenced local food habits. In the 1910s, European colonial powers introduced a number of foods to the Nauruans to mitigate impacts of drought and famine and add variety to the Nauruan diet. In the 1920s, the wife of one missionary taught Nauruans to fry fish in a pan rather than eat it raw. Over time, such changes led to skill loss (in fishing and food preservation) and dependence on foreign foods.[15]

A relatively sedentary lifestyle, including among children, is also contributing to rising obesity rates.[16]

Cultural standards and practices[edit]

Obesity in the Pacific Islands is also thought to be influenced by social and cultural factors (tambu foods), including past poor public education on diet, exercise and health.[17] Micronutrient deficiencies are also common.[18] Feasting and festivals are major parts of life,[19] imported foods have been given higher social status than local, healthier foods,[17] and historically a large body size was associated with wealth, power and beauty.[6][17] The Nauru term for satisfaction and feeling healthy, pweda, is the same as fullness or distention.[20]

High rates of obesity appear within 15 months of birth.[21]

Nutrient transmission[edit]

Nutrient transmission (change in diet) is the primary cause of the obesity epidemic in the Pacific Islands, with a high amount of imported foods high in salt and fat content.[22] Much of the local diet as of at least 2008 consists of processed, salty and calorie-dense imported food such as spam or corned beef, rather than traditional fresh fish, fruit and vegetables.[23][24][25][circular reference] Some foods high in saturated fat such as mutton flaps and turkey tails are sold in the Pacific islands due to relatively low wealth.[26]

Results[edit]

Obesity is leading to increased levels of illness, including type 2 diabetes[27] and heart diseases and other associated noncommunicable diseases.[22] Maternal obesity has been associated with preterm birth in Palau.[28]

A trend of childhood overweight and obesity rates is on the rise. In 2016, the highest rates of obesity for girls (over 30%) were in Nauru and for boys in the Cook Islands.[22]

Efforts to treat obesity[edit]

The World Health Organization implemented various fiscal policies to fight the rise of childhood obesity. Policies include (1) taxation of sugar sweetened beverages (20% SSB Tax) (2) New Marketing on Unhealthy Foods and Beverages to Children (3) International Code of Marketing on Breast Milk Substitutes.[22] Different nations implemented these WHO recommendations to a different extent.[22]

However, such existing public health programs based on nutrition and exercise, solely focusing on the domain of health, have achieved little success.[15] Histories of social values surrounding food and health is often overlooked, and may explain why food habits are hard to change through public health programs.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Lauren Streib (8 February 2007). "World's Fattest Countries". Forbes. Archived from the original on 25 January 2017.

- ^ "Fat of the land: Nauru tops obesity league". Independent.co.uk. 26 December 2010.

- ^ Bialik, By Carl (12 April 2013). "Island Where Obesity May Not be All It Seems". Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Snowdon, Wendy; Malakellis, Mary; Millar, Lynne; Swinburn, Boyd (2014). "Ability of body mass index and waist circumference to identify risk factors for non-communicable disease in the Pacific Islands". Obesity Research & Clinical Practice. 8 (1): e3645. doi:10.1016/j.orcp.2012.06.005. PMID24548575.

- ^ "Obesity - adult prevalence rate - the World Factbook".

- ^ a b c Marks, Kathy (26 December 2010). "Fat of the land: Nauru tops obesity league". The Independent. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- ^ Streib, Lauren (2 August 2007). "Nauru: 94.5% overweight". Forbes.com. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- ^ https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.LE00.IN?locations=TO

- ^ a b "How mutton flaps are killing Tonga". BBC News. 18 January 2016. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- ^ a b "Modern life means modern ills for obese Pacific islanders". AFP. 8 February 2008. Retrieved 21 August 2009.

- ^ Lin, Tracy Kuo; Teymourian, Yasmin; Tursini, Maitri Shila (14 April 2018). "The effect of sugar and processed food imports on the prevalence of overweight and obesity in 172 countries". Globalization and Health. Vol.14. doi:10.1186/s12992-018-0344-y.

- ^ "WHO | Pacific islanders pay heavy price for abandoning traditional diet". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 19 May 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- ^ "Diabetes prevalence (% of population ages 20 to 79) - Marshall Islands | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ Ichiho, Henry M.; Seremai, Johannes; Trinidad, Richard; Paul, Irene; Langidrik, Justina; Aitaoto, Nia (May 2013). "An assessment of non-communicable diseases, diabetes, and related risk factors in the Republic of the Marshall Islands, Kwajelein Atoll, Ebeye Island: a systems perspective". Hawai'i Journal of Medicine & Public Health: A Journal of Asia Pacific Medicine & Public Health. 72 (5 Suppl 1): 7786. ISSN2165-8242. PMC3689463. PMID23901366.

- ^ a b c McLennan, Amy K.; Ulijaszek, Stanley J. (June 2015). "Obesity emergence in the Pacific islands: why understanding colonial history and social change is important". Public Health Nutrition. 18 (8): 14991505. doi:10.1017/S136898001400175X. ISSN1368-9800. PMC10271720. PMID25166024. S2CID6823966.

- ^ "Pacific Islanders are world's fattest". BBC News. 28 November 2001. Retrieved 21 August 2009.

- ^ a b c "WHO Western Pacific | World Health Organization" (PDF).

- ^ "WHO | Pacific islanders pay heavy price for abandoning traditional diet". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 19 May 2012. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ "Pacific islanders are world's fattest". 28 November 2001.

- ^ McLennan, AK (2015). "Bringing everyday life into the study of 'lifestyle diseases': lessons from an ethnographic investigation of obesity in Nauru" (PDF). Journal of Anthropological Society of Oxford. 7: 286301.

- ^ "Samoan obesity epidemic starts at birth".

- ^ a b c d e Foster, Nicole; Thow, Anne Marie; Unwin, Nigel; Alvarado, Miriam; Samuels, T. Alafia (2018). "Regulatory measures to fight obesity in Small Island Developing States of the Caribbean and Pacific, 2015 2017". Revista Panamericana de Salud Pblica. 42: e191. doi:10.26633/RPSP.2018.191. ISSN1020-4989. PMC6386011. PMID31093218.

- ^ Nick Squires (12 April 2008). "Spam at heart of South Pacific obesity crisis". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 21 August 2009.

- ^ Phil Mercer (26 February 2007). "South Pacific Leads the World in Obesity". Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ^ Obesity in Nauru#Causes

- ^ "How mutton flaps are killing Tonga". BBC News. 18 January 2016.

- ^ Colagiuri, S; Colagiuri, R; Na'Ati, S; Muimuiheata, S; Hussain, Z; Palu, T (2002). "The Prevalence of Diabetes in the Kingdom of Tonga". Diabetes Care. 25 (8): 137883. doi:10.2337/diacare.25.8.1378. PMID12145238.

- ^ Kaforau, Lydia S. K.; Tessema, Gizachew A.; Jancey, Jonine; Dhamrait, Gursimran; Bugoro, Hugo; Pereira, Gavin (1 April 2022). "Prevalence and risk factors of adverse birth outcomes in the Pacific Island region: A scoping review". The Lancet Regional Health Western Pacific. 21: 100402. doi:10.1016/j.lanwpc.2022.100402. ISSN2666-6065. PMC8873950. PMID35243458.

Tongas obesity epidemic is causing big trouble in paradise

At first impression the Royal Kingdom of Tonga in the South Pacific is the very embodiment of an imagined tropical paradise.

Coconut trees sway in a warm ocean breeze, the pace of life beats slower and the people are laid-back and friendly.

Even the name of its capital Nukualofa means abode of love.

But today theres big trouble in this little known Polynesian nation, which lies 2,400 kilometres north of New Zealand.

And the trouble is Tongas obesity epidemic.

According to a recent academic paper published by the UK medical magazine Lancet, Tonga is now the most obese country in the world.

Today over 90 per cent of adults in this island nation of 107,000 people are either obese or overweight using the internationally-accepted BMI (body mass index) rating, which calculates levels of obesity from a persons height, weight and build.

Equally worryingly, the World Health Organization (WHO) says that almost a quarter of Tongans aged over 30 years are now suffering from Type 2 diabetes.

Many Tongans, it would appear, are quite literally eating themselves to death. This is also true of seven other Polynesian states, including Fiji, Samoa and American Samoa, which are also amongst the worlds ten most obese nations.

In Tonga, average life expectancy has dropped from 72 years in 2012 to 67 years today. And this former British Protectorate is now facing an epidemic of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as cardiovascular diseases and respiratory illnesses, which are all linked to diabetes, as highlighted in a recent report by the Asia Pacific Observatory on Health Systems and Policies.

Few families in this archipelago of 170 islands have escaped the scourge of diabetes, which in Tonga is predominantly caused by the sedentary lifestyle of its citizens and the lack of fruit and vegetables in the modern Tonga diet.

Another major contributing factor is the popularity of imported junk meat such as tinned corned beef, cheap chicken, turkey tails and mutton flaps a fatty cut of lamb removed from beneath the ribs that is seldom sold in New Zealand, where it is sourced, but imported to the South Pacific instead.

Tsunami of obesity and diabetes

A visit to Nukualofas Vaiola Hospital graphically illustrates the tsunami of obesity and diabetes that is threatening to overwhelm this island nation.

Every weekday the hospitals diabetes clinic is crowded with patients waiting for treatment.

Many of them are in wheelchairs and have had a foot or leg amputated because of diabetic foot infections or sepsis. Others have foot ulcers or have had a debridement in a bid to stop infection spreading through their bodies.

During a recent visit to Vaiola Hospital Equal Times met 72-year-old Petilina Malie, who was in the surgical ward waiting to have her left foot amputated.

Petilina, a mother of 12, had been a diabetic for 20 years. A small boil on the heel of her foot had turned to sepsis and the infection was spreading, inexorably, up her leg and threatening her life. Amputation of her foot, after two failed debridements, was the only solution.

Anxiety and fear were etched on the matriarchs face. Fighting back the tears, her son Leimoni, a 47-year-old fisherman, told Equal Times: We have to remain strong for my mother. I dont want to lose her to this disease. I pray to God that todays treatment will free her from pain and give her some peace.

Obesity and subsequent diabetes, triggered by poor health choices, had had a devastating effect on the family, Leimoni conceded. Two other relatives were also suffering from diabetes, he said.

We should encourage people who have not got diabetes to be more aware of what they eat and how they live, to live healthier lives.

People should be more active and do some physical work, sweat a little; anything that would push away this disease. This means eating right and not just following our tastes and fancies, he said.

Last year Vaiolas two surgeons carried out 16 major above- and below-the-knee amputations, as well as 43 lesser amputations, such as cutting off toes or the partial or total removal of a foot.

NCDs and so-called lifestyle diseases particularly diabetes and associated cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases account for 74 per cent of all deaths in Tonga.

In 2000 the country spent the equivalent of US$163 per person on health. By last year the figure had increased to US$245, representing around 12 per cent of total government expenditure.

Almost half of Tongas health budget is provided by donor and development funding. Vaiola Hospital, for example, was mostly rebuilt and refurbished with funding from the Japanese International Cooperation Agency (JICA). Other big funders include WHO and the governments of Australia and New Zealand.

The impact of globalisation

Globalisation has been a major factor in feeding the obesity crisis.

In 2004 Tonga was the first Pacific island country to develop a comprehensive health strategy to combat the nascent menace of obesity.

But a year later the country joined the World Trade Organisation, reduced its import tariffs and opened its domestic market to foreign investment.

The result has been an even greater reliance on food imports of relatively cheap fatty meats, refined carbohydrates and other packaged foods with high sugar and salt content.

In essence, many families have abandoned a traditional healthy diet of fish, fruit and vegetables for imported junk food.

NCDs are the greatest challenge facing my country right now, Dr. Siale Akauola, Tongas director of health told Equal Times.

In the olden days people used to hunt. They would go fishing and bring the fish from the sea. But nowadays theres a shop there. Whats available is not always the healthiest choice.

He continued: Urbanisation is something thats pretty new here. We are aware that this is the normal transition of a population being exposed to a new environment, new fast food.

We have problems in the world today because of the technology of producing food, so fast, so efficient, using a lot of salty, cheap food.

This is a global problem. We are aware of that, and we are aware its not only our nation having a headache over the whole thing, said Dr. Siale.

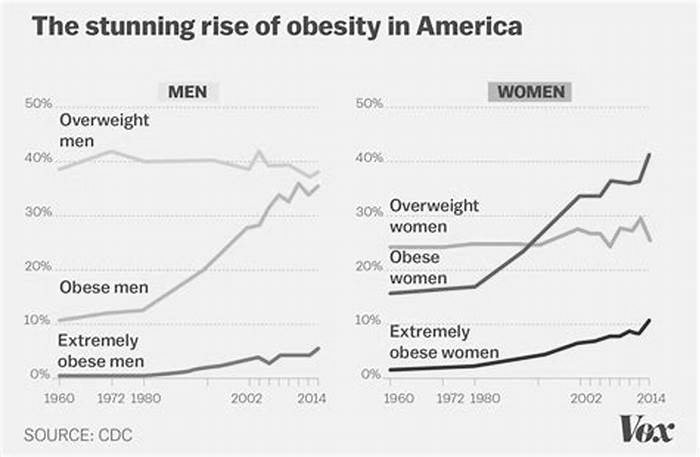

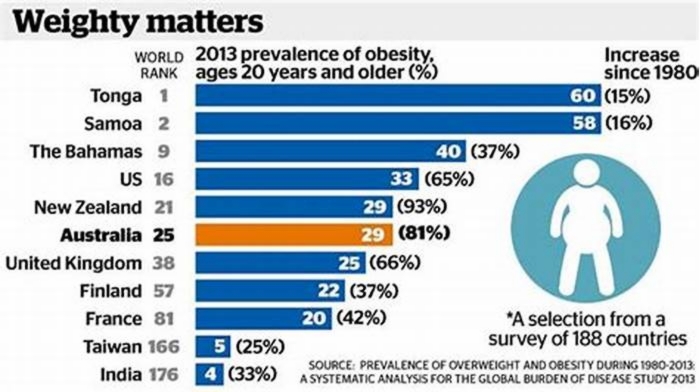

Around the world an estimated 600 million people are obese. The number has doubled since 1980.

Most striking of all, perhaps, is the fact that in the last 33 years not a single country has been able to reduce its rate of obesity.

Undaunted, Tongas government has now stepped up its fight against the disorder.

Fighting back with a fat tax

Last year the government imposed an additional excise tax a so-called fat tax of 40 seniti a kilo (around US$0.15) on various imported foods, including industrial chicken, mutton flaps and turkey tails.

And earlier this year Tonga Health, the semi-autonomous health agency spearheading the campaign against obesity, was given new offices at Vaiola Hospital to accommodate its expanded team of 13 health workers.

Currently we are focusing on physical activity and healthy eating, the two risk factors that really impact our population, said Tonga Health program coordinator Monica Tuipulotu.

We Tongans just love to eat. On every occasion we have food. In our culture the more food you serve, the more love you have for that person. And Im not just talking about a cup of tea. It comes with a lot of carbs, a lot of fats and a lot of sugar and salty foods.

We know its really hard to change the culture and the lifestyle. It wont happen overnight. It will take a long time.

Tonga Health also oversees a flagship programme called Mai-e-Nima, or Five-a-Day, which encourages schoolchildren to eat at least five portions of fruit and vegetables a day.

Tonga is number one with obesity in the world. Its difficult to change the adults in our generation, Minoru Nishi, chair of the Mai-e-Nima campaign told Equal Times.

We need to tackle the problem with the primary school kids because I firmly believe that if we change the kids we change a generation.

It all comes down to our personal choices and what we eat and drink.

Petilina Malie has had her left foot cut off because of lifestyle-related diabetes.

In its ongoing battle against obesity it could be said that Tonga, too, is on the operating table.