Why is Japan s obesity rate so low

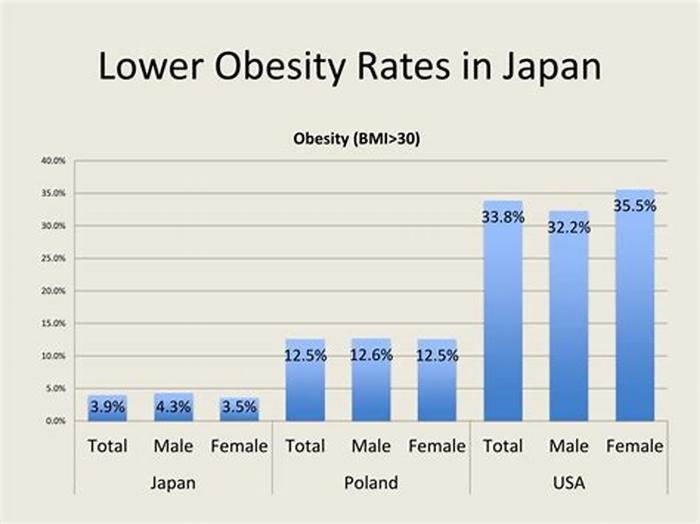

More than one billion adults are overweight worldwide, and more than 300 million of them clinically obese, raising the risk of many serious diseases. Only 3.6 percent of Japanese have a body mass index (BMI) over 30, which is the international standard for obesity, whereas 32.0 percent of Americans do. A total of 66.5 percent of Americans have a BMI over 25, making them overweight, but only 24.7 percent of Japanese. This paper examines the reasons Japan has one of the lowest rates of obesity in the world and the United States one of the highest, giving particular attention to underlying economic factors that might be influenced by policy changes. The average person in Japan consumes over 200 fewer calories per day than the average American. Food prices are substantially higher in Japan, but the traditional Japanese dietary habits, although changing, are also healthier. The Japanese are also far more physically active than Americans, but not because they do more planned physical exercise. They walk more as part of their daily lives. They walk more because the cost of driving an automobile is far higher in Japan, whereas public transportation is typically very convenient, but normally requires more walking than the use of a car. In terms of policy solutions, economic incentives could be structured to encourage Americans to drive less and use public transportation more, which would typically also mean walking more.

Title Why Is the Obesity Rate So Low in Japan and High in the U.S.? Some Possible Economic Explanations

Issue Date 2006

Publication Type Working or Discussion Paper

Record Identifier https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/14321

PURL Identifier http://purl.umn.edu/14321

Language English

Total Pages 26

JEL Codes D12 I 11

Series Statement Working Paper 06-02

Why is Japan's obesity rate so low? One influencer says these cultural habits are the key

Join Fox News for access to this content

Plus special access to select articles and other premium content with your account - free of charge.

Please enter a valid email address.

It's everywhere from diet pills to the GLP-1 craze, promotions for healthier foods and commercials for gym memberships at the start of every new year.

Americans want to lose weight, but why is obesity so common that it drives what's among the most popular New Year's resolutions out there? Better yet, what's keeping some other high-income nations, like Japan, from having the same widespread issue?

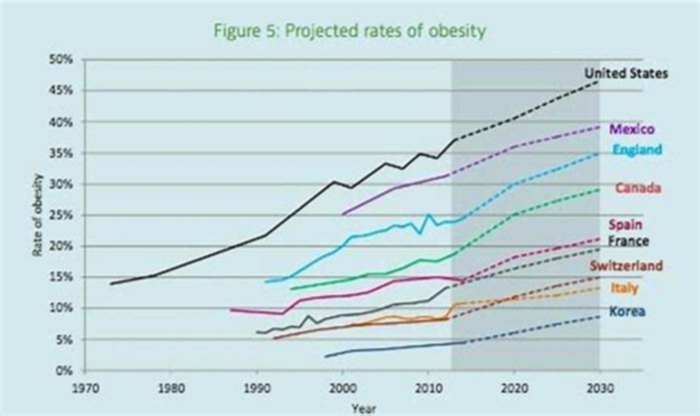

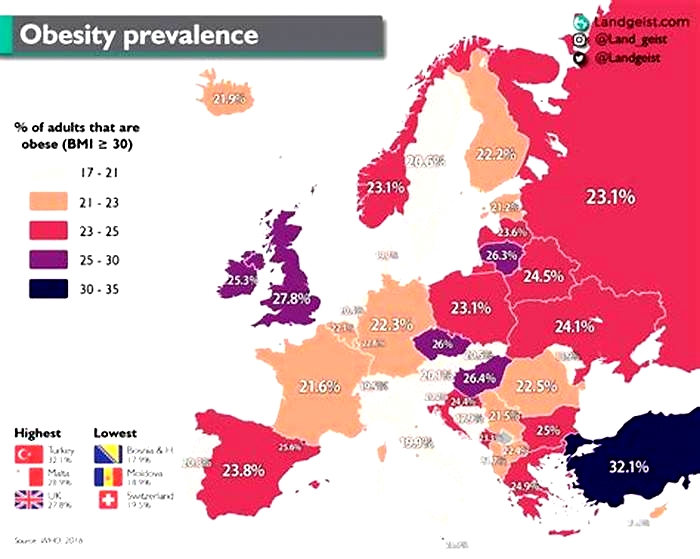

According to Dr. Michael Hunter, a radiation oncologist from the Seattle area, Japan and Korea lead high-income nations with the lowest obesity ratings while the United States tips the scales at the highest. Japan's use of the "Metabo Law" has been in the news recently as the United Kingdom considers a similar measure to combat obesity; Japan's 2008 law requires waistline measurements of citizens between 40 and 74 in their annual checkups, and those who exceed the limit are steered toward healthier practices.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) classifies anyone with a BMI of 30-39 as obese, with those of a BMI of 40 or above falling under the "severe" obesity label.

OBESITY MAPS: CDC REVEALS WHICH US STATES HAVE THE HIGHEST BODY MASS INDEX AMONG RESIDENTS

Japan's obesity rate hovers around 3-4% while America's is over a shocking 40%. (iStock/PETER PARKS/AFP via Getty Images)

Data from The Global Obesity Observatory supports the claim, finding that 43% of Americans are considered obese, a percentage exponentially higher than the modest 4.5% for their Japanese counterparts.

Some say it boils down to a combination of activity level, lifestyle, diet and culture, including Hunter, who pointed out the ways Japanese kids head off to school on foot and the population as a whole tends to opt for smaller portion sizes.

To get an inside perspective, Fox News Digital reached out to Japanese YouTuber Yoko Ishii to hear her thoughts about the cultural contrast between the two nations.

"I think that Japanese people begin our health journey starting in elementary school, because, unlike America, children walk to school instead of being driven to school. And then, under our compulsory education, we learn about home economics and that's where we learn about nutrition, balance and so on," she said on Tuesday.

"We cook in class as well, just like in science class, you do experiments. We actually do it and get the hang of it. In school, meals from elementary school to junior high school meals are provided, so that means that, each day, we see the full set of lunch. It's like the ideal lunch, right? It's different in America, but here, there's a soup and white rice and then a couple of other dishes and sometimes a dessert and so on with a milk, so we learn about the balance and what we should eat and what not to eat."

SEVERE CHILDHOOD OBESITY HAS INCREASED IN THE US: NEW STUDY

According to the CDC, the threshold for obesity is having a BMI or 30 or greater. (iStock)

Ishii said, from childhood, Japanese people establish a lifestyle that involves a lot of physical activity, even walking to school instead of driving when they reach high school. If school is too far away, however, students will often take a train or ride a bicycle, she explained.

But beyond getting to school, students get active there as well. There are no janitors, so students clean the building themselves. There are also a number of school clubs that enable Japanese students to get active.

"Some people go to cultural clubs. But I myself, I belonged to a kendo club. I used to do kendo [a Japanese martial art] and others would belong to judo or baseball or soccer or basketball, volleyball, whatever they wanted to. So we learned to exercise in school," Ishii said.

"I guess that while growing up, we established the system in ourselves to exercise, and to depend on ourselves and think by ourselves."

HEART DISEASE DEATHS LINKED TO OBESITY HAVE TRIPLED IN 20 YEARS, STUDY FOUND: INCREASING BURDEN

Japanese students are more likely to walk to and from school instead of being driven by car like most American students. (Stanislav Kogiku/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images)

Health consciousness is even imbued in the country's variety shows.

"We have lots of health-related shows, so there are quizzes about health and food, and we have to know about it. If you don't, that's kind of an embarrassment, so you have to learn all these things so that you can keep up with other people," Ishii said.

It's even a part of Japan's legal and corporate structure to some extent. According to a website for the country's Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, the country conducts annual physical exams including waist measurements on eligible people aged 40 to 74 to help prevent lifestyle-related illnesses, particularly related to metabolic syndrome (a cluster of weight-related conditions that include high blood pressure, insulin resistance and elevated bad cholesterol, among others).

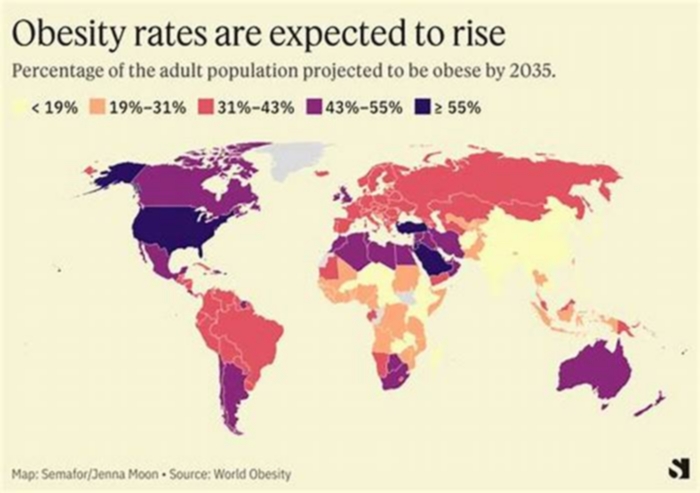

MORE THAN HALF THE WORLD'S POPULATION WILL BE OBESE OR OVERWEIGHT BY 2035, SAYS NEW REPORT

"Specialist staff (public health nurses, registered dietitians, etc.) support those who are at high risk of developing lifestyle-related diseases and who can expect many benefits in preventing lifestyle-related diseases through lifestyle changes," the site reads, translated from Japanese.

The "Metabo Law," aimed at curbing rising healthcare costs in the country, according to a Wall Street Journal report from 2008, urges people with larger-than-accepted waistlines to shed the extra pounds or face "compulsory diet advice and follow-up visits" for several months.

Ishii said the idea hasn't been so shocking to Japanese people, however.

"We don't think about it [the law] much at all. We did start to hear about it, but we were always aware that being in a good health state is important, so nothing really changed," she said.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

"I guess the government wants to cut the expense for the medical area. In order to do that, you want to keep your citizens healthy, so that's why I guess that they are trying to raise awareness."

Why has Japan become the worlds most long-lived country: insights from a food and nutrition perspective

World Health Organization (WHO). Life expectancy and Healthy life expectancy data by country. http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.SDG2016LEX?lang=en. Accessed March 1, 2020.

World Health Organization (WHO). Global Health Estimates 2016: deaths by cause, age, sex, by country and by region, 20002016. https://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/estimates/en/. Accessed March 1, 2020.

Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Japan. Vital statistics. https://www.e-stat.go.jp/. Accessed March 1, 2020.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). OECD health statistics 2019. https://www.oecd.org/health/health-data.htm. Accessed March 1, 2020.

World Health Organization (WHO). WHO mortality database. http://apps.who.int/healthinfo/statistics/mortality/whodpms/. Accessed March 1, 2020.

World Health Organization (WHO). Global Health Observatory data repository, noncommunicable diseases, risk factors. http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.A867?lang=en. Accessed March 1, 2020.

Japan Health Promotion & Fitness Foundation. Tobacco or health. http://www.health-net.or.jp/tobacco/menu02.html. Accessed March 1, 2020.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: FAOSTAT. http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#home. Accessed March 1, 2020.

Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Japan. National health and nutrition survey. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/kenkou/kenkou_eiyou_chousa.html. Accessed March 1, 2020.

Yamagishi K, Iso H, Kokubo Y, Saito I, Yatsuya H, Ishihara J, et al. Dietary intake of saturated fatty acids and incident stroke and coronary heart disease in Japanese communities: the JPHC Study. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:122532.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Yamagishi K, Iso H, Tsugane S. Saturated fat intake and cardiovascular disease in Japanese population. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2015;22:4359.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Iso H, Kobayashi M, Ishihara J, Sasaki S, Okada K, Kita Y, et al. Intake of fish and n3 fatty acids and risk of coronary heart disease among Japanese: the Japan Public Health Center-Based (JPHC) Study Cohort I. Circulation. 2006;113:195202.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Sekikawa A, Doyle MF, Kuller LH. Recent findings of long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCn-3 PUFAs) on atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease (CHD) contrasting studies in Western countries to Japan. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2015;25:71723.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Messina MJ, Persky V, Setchell KD, Barnes S. Soy intake and cancer risk: a review of the in vitro and in vivo data. Nutr Cancer. 1994;21:11331.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Sacks FM, Lichtenstein A, Van Horn L, Harris W, Kris-Etherton P, Winston M, American Heart Association Nutrition Committee. Soy protein, isoflavones, and cardiovascular health: an American Heart Association Science Advisory for professionals from the Nutrition Committee. Circulation. 2006;113:103444.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Yamamoto S, Sobue T, Kobayashi M, Sasaki S, Tsugane S. Soy, isoflavones, and breast cancer risk in Japan. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:90613.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Xie Q, Chen ML, Qin Y, Zhang QY, Xu HX, Zhou Y, et al. Isoflavone consumption and risk of breast cancer: a dose-response meta-analysis of observational studies. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2013;22:11827.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Kurahashi N, Iwasaki M, Sasazuki S, Otani T, Inoue M, Tsugane S. Soy product and isoflavone consumption in relation to prostate cancer in Japanese men. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2007;16:53845.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Yan L, Spitznagel EL. Soy consumption and prostate cancer risk in men: a revisit of a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:115563.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Kokubo Y, Iso H, Ishihara J, Okada K, Inoue M, Tsugane S. Association of dietary intake of soy, beans, and isoflavones with risk of cerebral and myocardial infarctions in Japanese populations: the Japan Public Health Center-based (JPHC) study cohort I. Circulation. 2007;116:255362.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Yan Z, Zhang X, Li C, Jiao S, Dong W. Association between consumption of soy and risk of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2017;24:73547.

Article Google Scholar

Katagiri R, Sawada N, Goto A, Yamaji T, Iwasaki M, Noda M, et al. Association of soy and fermented soy product intake with total and cause specific mortality: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2020;368:m34.

Article Google Scholar

Budhathoki S, Sawada N, Iwasaki M, Yamaji T, Goto A, Kotemori A, et al. Association of animal and plant protein intake with all-cause and cause-specific mortality in a Japanese cohort. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:150918.

Article Google Scholar

Hruby A, Manson JE, Qi L, Malik VS, Rimm EB, Sun Q, et al. Determinants and consequences of obesity. Am J Public Health. 2016;106:165662.

Article Google Scholar

Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA, Desprs JP, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease risk. Circulation. 2010;121:135664.

Article Google Scholar

Saito E, Inoue M, Sawada N, Shimazu T, Yamaji T, Iwasaki M, et al. Association of green tea consumption with mortality due to all causes and major causes of death in a Japanese population: the Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study (JPHC Study). Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25:5128.

Article Google Scholar

Abe SK, Saito E, Sawada N, Tsugane S, Ito H, Lin Y, et al. Green tea consumption and mortality in Japanese men and women: a pooled analysis of eight population-based cohort studies in Japan. Eur J Epidemiol. 2019;34:91726.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Kobayashi M, Sasazuki S, Shimazu T, Sawada N, Yamaji T, Iwasaki M, et al. Association of dietary diversity with total mortality and major causes of mortality in the Japanese population: JPHC study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2020;74:5466.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Kurotani K, Akter S, Kashino I, Goto A, Mizoue T, Noda M, et al. Quality of diet and mortality among Japanese men and women: Japan Public Health Center based prospective study. BMJ. 2016;352:i1209.

Article Google Scholar

Shimamoto T, Iso H, Iida M, Komachi Y. Epidemiology of cerebrovascular disease: stroke epidemic in Japan. J Epidemiol. 1996;6:S437.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Yu E, Hu FB. Dairy products, dairy fatty acids, and the prevention of cardiometabolic disease: a review of recent evidence. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2018;20:24.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Stamler J, Rose G, Stamler R, Elliott P, Dyer A, Marmot M. INTERSALT study findings. Public health and medical care implications. Hypertension. 1989;14:5707.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Tsugane S. Salt, salted food intake, and risk of gastric cancer: epidemiologic evidence. Cancer Sci. 2005;96:16.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Joossens JV, Hill MJ, Elliott P, Stamler R, Lesaffre E, Dyer A, et al. Dietary salt, nitrate and stomach cancer mortality in 24 countries. European Cancer Prevention (ECP) and the INTERSALT Cooperative Research Group. Int J Epidemiol. 1996;25:494504.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Willett WC. Overview and perspective in human nutrition. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2008;17 Suppl 1:14.

PubMed Google Scholar

Key TJ, Bradbury KE, Perez-Cornago A, Sinha R, Tsilidis KK, Tsugane S. Diet, nutrition and cancer risk: what do we know and what is the way forward? BMJ. 2020;368:m511.

Article Google Scholar

Inoue M, Sawada N, Matsuda T, Iwasaki M, Sasazuki S, Shimazu T, et al. Attributable causes of cancer in Japan in 2005-systematic assessment to estimate current burden of cancer attributable to known preventable risk factors in Japan. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:13629.

Article CAS Google Scholar