Why does Korea have the lowest obesity rate

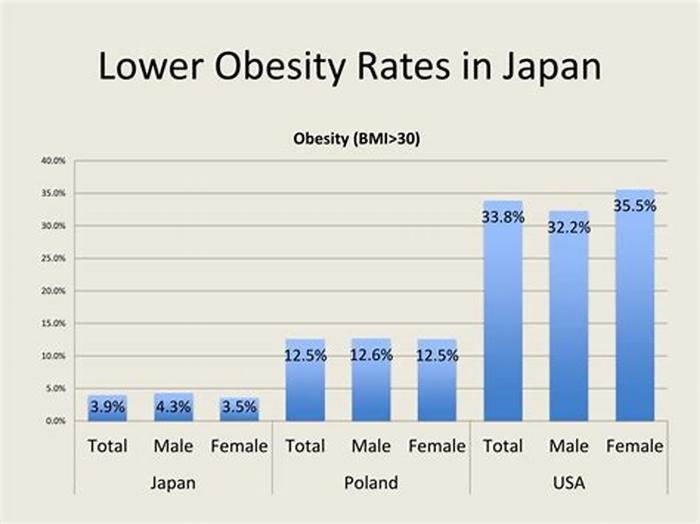

More than one billion adults are overweight worldwide, and more than 300 million of them clinically obese, raising the risk of many serious diseases. Only 3.6 percent of Japanese have a body mass index (BMI) over 30, which is the international standard for obesity, whereas 32.0 percent of Americans do. A total of 66.5 percent of Americans have a BMI over 25, making them overweight, but only 24.7 percent of Japanese. This paper examines the reasons Japan has one of the lowest rates of obesity in the world and the United States one of the highest, giving particular attention to underlying economic factors that might be influenced by policy changes. The average person in Japan consumes over 200 fewer calories per day than the average American. Food prices are substantially higher in Japan, but the traditional Japanese dietary habits, although changing, are also healthier. The Japanese are also far more physically active than Americans, but not because they do more planned physical exercise. They walk more as part of their daily lives. They walk more because the cost of driving an automobile is far higher in Japan, whereas public transportation is typically very convenient, but normally requires more walking than the use of a car. In terms of policy solutions, economic incentives could be structured to encourage Americans to drive less and use public transportation more, which would typically also mean walking more.

Title Why Is the Obesity Rate So Low in Japan and High in the U.S.? Some Possible Economic Explanations

Issue Date 2006

Publication Type Working or Discussion Paper

Record Identifier https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/14321

PURL Identifier http://purl.umn.edu/14321

Language English

Total Pages 26

JEL Codes D12 I 11

Series Statement Working Paper 06-02

South Korea

Obesity in Children and Adolescents: 2022 Update of Clinical Practice Guidelines for Obesity by the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity

This article summarizes the clinical practice guidelines for obesity in children and adolescents that are included in the 8th edition of the Clinical Practice Guidelines for Obesity of the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity.

| Categories: | Evidence of Management/treatment guidelines |

| Year(s): | 2022 (ongoing) |

| Target age group: | Children |

| Organisation: | Korean Society for the Study of Obesity |

| Findoutmore: | pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov |

| References: | Kang E, Hong YH, Kim J, Chung S, Kim KK, Haam JH, Kim BT, Kim EM, Park JH, Rhee SY, Kang JH, Rhie YJ. Obesity in Children and Adolescents: 2022 Update of Clinical Practice Guidelines for Obesity by the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity. J Obes Metab Syndr. 2024 Jan 9. doi: 10.7570/jomes23060. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 38193204. |

2020 Korean Society for the Study of Obesity Guidelines for the Management of Obesity in Korea

The 2020 Korean Society for the Study of Obesity Guideline for the Management of Obesity in Korea summarizes evidence-based recommendations and treatment guidelines.

| Categories: | Evidence of Management/treatment guidelines |

| Year(s): | 2020 (ongoing) |

| Target age group: | Adults |

| Organisation: | Korean Society for the Study of Obesity |

| Findoutmore: | www.jomes.org |

| References: | Kim BY, Kang SM, Kang JH, Kang SY, Kim KK, Kim KB, Kim B, Kim SJ, Kim YH, Kim JH, Kim JH, Kim EM, Nam GE, Park JY, Son JW, Shin YA, Shin HJ, Oh TJ, Hyug L, Jeon EJ, Chung S, Hong YH, Kim CH; Committee of Clinical Practice Guidelines, Korean Society for the Study of Obesity (KSSO). 2020 Korean Society for the Study of Obesity Guidelines for the Management of Obesity in Korea. J Obes Metab Syndr. 2021 May 28. doi: 10.7570/jomes21022. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34045368. |

2018 Korean Society for the Study of Obesity Guideline for the Management of Obesity in Korea

These guidelines focus on guiding clinicians and patients to manage obesity more effectively. The recommendations and treatment algorithms can serve as a guide for the evaluation, prevention, and management of overweight and obesity.

| Categories: | Evidence of Management/treatment guidelines |

| Year(s): | 2018 (ongoing) |

| Target age group: | Adults |

| Organisation: | Korean Society for the Study of Obesity |

| Linkeddocument: | Download linked document |

| References: | Seo MH, Lee WY, Kim SS, et al. 2018 Korean Society for the Study of Obesity Guideline for the Management of Obesity in Korea [published correction appears in J Obes Metab Syndr. 2019 Jun;28(2):143].J Obes Metab Syndr. 2019;28(1):40-45. doi:10.7570/jomes.2019.28.1.40 |

Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of pediatric obesity: recommendations from the Committee on Pediatric Obesity of the Korean Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutritio

The following areas were systematically reviewed, especially on the basis of all available references published in South Korea and worldwide, and new guidelines were established in each area with the strength of recommendations based on the levels of evidence: (1) definition and diagnosis of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents; (2) principles of treatment of pediatric obesity; (3) behavioral interventions for children and adolescents with obesity, including diet, exercise, lifestyle, and mental health; (4) pharmacotherapy; and (5) bariatric surgery.

| Categories: | Evidence of Management/treatment guidelines |

| Year(s): | 2018 (ongoing) |

| Target age group: | Children |

| Organisation: | Health Promotion Administryation, Ministry of Health & Welfare |

| Linkeddocument: | Download linked document |

| References: | Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of pediatric obesity: recommendations from the Committee on Pediatric Obesity of the Korean Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition. Clin Exp Pediatr. 2019;62(1):3-21. Published online December 27, 2018. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3345/kjp.2018.07360 |

Comprehensive plan for Obesity Prevention and Control

South Korea's national obesity strategy, including physical activity guidelines

| Categories: | Evidence of National Obesity Strategy/Policy or Action planEvidence of Nutritional or Health Strategy/ Guidelines/Policy/Action planEvidence of Physical Activity Guidelines/Policy |

| Year(s): | 2018 (ongoing) |

| Target age group: | Adults and children |

| Organisation: | Joint ministries |

| Linkeddocument: | Download linked document |

NCD Country Profiles 2018 (Obesity Targets)

The profiles also provide data on the key metabolic risk factors, namely raised blood pressure, raised blood glucose and obesity and National Targets on Obesity (as of 2017)

| Categories: | Evidence of Obesity Target |

| Year(s): | 2017 (ongoing) |

| Target age group: | Adults and children |

| Organisation: | World Health Organisation |

| References: | Noncommunicable diseases country profiles 2018. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. |

White Paper, Ministry of Food and Drug Safety

| Categories: | Labelling Regulation/Guidelines |

| Year(s): | 2016 (ongoing) |

| Target age group: | Adults and children |

| Organisation: | Ministry of Food and Drug Safety |

| Linkeddocument: | Download linked document |

The Physical Activity Guide for Koreans

Korea's physical activity strategy and guidelines.

| Categories: | Evidence of Physical Activity Guidelines/Policy |

| Year(s): | 2013 (ongoing) |

| Target age group: | Adults and children |

| Organisation: | Ministry of Health and Welfare |

The Special Act on the Safety Management of Childrens Dietary Life

The Special Act on the Safety Management of Childrens Dietary Life covers a series of policies to prevent obesity and improve children's diet. Article 10 stipulates that TV advertising to children under 18 years of age is prohibited for specific categories of food before, during and after programmes shown between 5pm7pm and during other childrens programmes. The restriction also applies to advertising on TV, radio and the internet that includes gratuitous incentives to purchase (eg free toys).The Act also sets nutrition standards for food sold on school premises and prevents the sale of sugar drinks and other energy-dense and nutrient-poor foods entirely.

| Categories: | Evidence of School Food RegulationsEvidence of Marketing Guidelines/Policy |

| Year(s): | 2009 (ongoing) |

| Target age group: | Children |

| Organisation: | Government |

| Findoutmore: | elaw.klri.re.kr |

General dietary guidelines for Koreans

In 1991, the National dietary guidelines were first published by the Ministry of Health and Welfare. In 2002-2003, general and age-based guidelines were announced and revised in 2008-2009. In 2016, the General Dietary Guidelines for Koreans were established as common guidelines of inter-government ministries.

Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of pediatric obesity

Provides an evidence-based systematic approach to childhood obesity in South Korea. Emphasises a family-based, comprehensive, multidisciplinary behavioural intervention which focuses on modifying lifestyle (calorie-controlled balanced diet, active vigorous physical activity and exercise, and reduction of sedentary habits, and support by the entire family, school, and community). Also emphasises the importance of starting early in life.

| Categories: | Evidence of Management/treatment guidelines |

| Target age group: | Adults and children |

| Organisation: | Pediatric Obesity Committee of the KSPGHAN Guideline Task Force (TF) |

| Findoutmore: | www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov |

| Linkeddocument: | Download linked document |

| References: | Yong et al. 2019 Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of pediatric obesity: recommendations from the Committee on Pediatric Obesity of the Korean Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition. Korean J Pediatr 2019;62(1). pp. 3-21. |

Code of Advertising Ethics

The Code states that advertising for children and youth should not express anything that might spoil them physically or morally. It also states that Criteria for concrete activities shall conform to the ICC Advertising Activities Standards"

| Categories (partial): | Evidence of Marketing Guidelines/Policy |

| Target age group: | Children |

| Organisation: | Korea Federation of Advertising Associations |

| References: | Currently a web link to this code is unavailable. If you are aware of the location of this document/intervention, please contact us at [email protected] |

GNPR 2016-17 (q7) Breastfeeeding promotion and/or counselling

WHO Global Nutrition Policy Review 2016-2017 reported the evidence of breastfeeding promotion and/or counselling (q7)

| Categories: | Evidence of Breastfeeding promotion or related activity |

| Target age group: | Adults |

| Organisation: | Ministry of Health (information provided by the GINA progam) |

| Findoutmore: | extranet.who.int |

| References: | Information provided with kind permission of WHO Global database on the Implementation of Nutrition Action (GINA): https://extranet.who.int/nutrition/gina/en |

Special Act on Safety Control of Children's Dietary Life

The South Korean Special Act on Safety Control of Children's Dietary Life recommends colour-coded labelling for use on the front of pre-packaged children's "favourite food" including cookies/candies/popsicles, breads, chocolates, dairy products, sausage (fish or meat based), some beverages, instant noodles and fast food (seaweed rolls, hamburgers, sandwiches). Guidance for the front-of-pack colour-coded labelling was issued by Public Notice (2011), and outlines three permitted designs using green, amber and red to identify whether products contain low, medium or high levels of total sugars, fat, saturated fat, and sodium.

The Foods Labelling Standards & The Labelling Standard for Health Functional Food

In South Korea, a nutrient list must be provided on select categories of pre-packaged food, including cookies/candies/popsicles, breads and dumplings, cocoa products, jams, oils, noodles and pasta, drinks and beverages, and food of special use. The Foods Labelling Standards were first enacted in 1996, and the Labelling Standard for Health Functional Food in 2004; both Standards have been revised several times since then. Based on the 1st Master Plan on Reducing Sugar Intake 201620 and the 2016 White Paper by the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety, further categories will be required to bear nutrient lists with a three-stage implementation between 2017 and 2022 (including cereals, ready-to-eat products and ready-to-cook products in 2017; dressings and sauces in 201819; Korean-style boiled grain-/meat-/fish-based food and processed food based on fruit or vegetable purees/pastes in 202022).

No actions could be found for the above criteria.

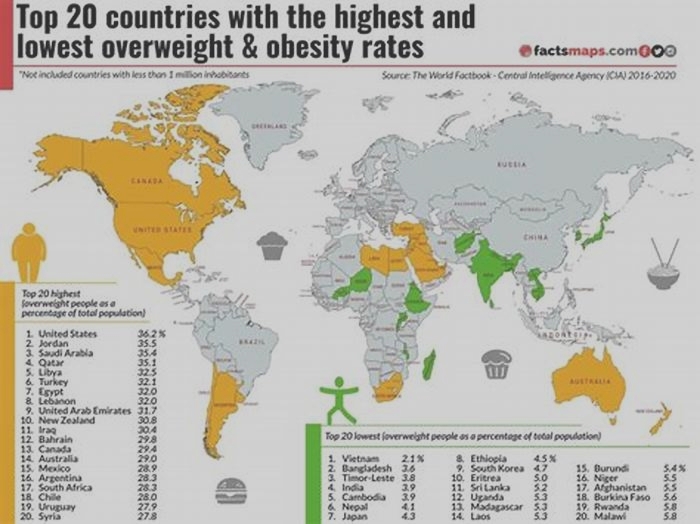

Obesity Rates by Country 2024

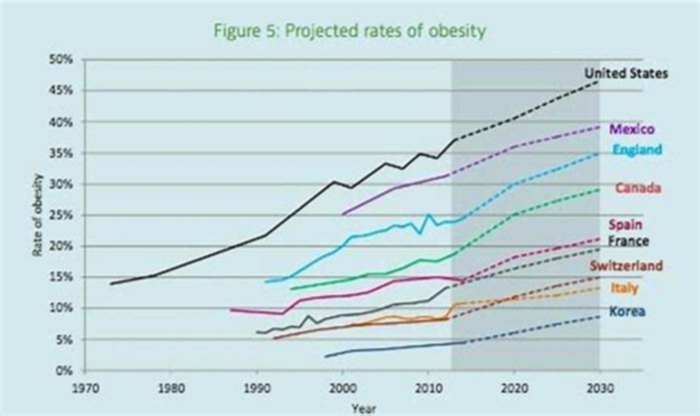

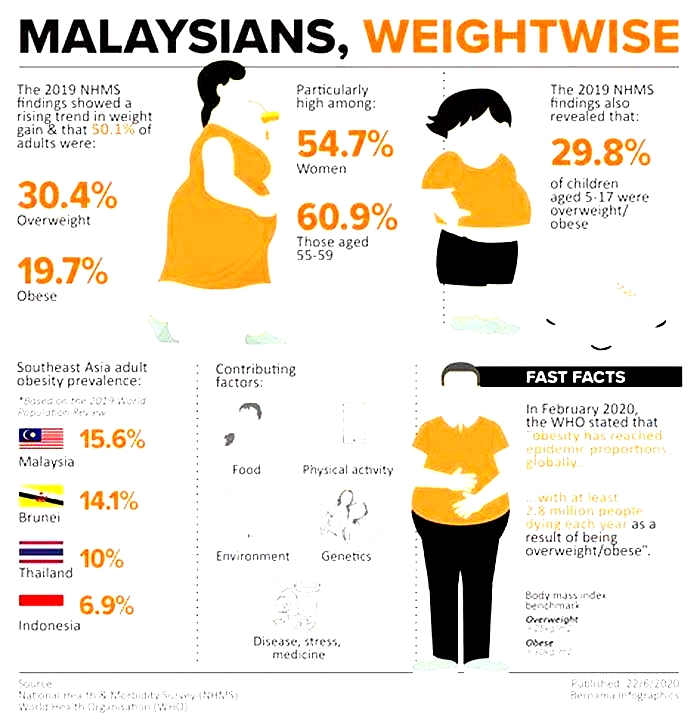

When a person's weight is higher than what is considered healthy for their height, their condition is described as overweight or obese. Bodyweight results from several factors, such as poor nutritional choices, overeating, genetics, culture, and metabolism. Obesity is linked to many health complications and diseases, such as diabetes, heart disease, certain types of cancer, and stroke. Additionally, obesity is the leading preventable cause of preventable death. Despite the negative effects these conditions can have on one's health, more people are overweight or obese today than ever before in history. In fact, obesity is considered a modern epidemic in most parts of the world. Worldwide obesity has nearly tripled since 1975, with about 13% of adults being obese and about 39% of adults being overweight.

BMI explained

The most commonly used method of measuring obesity is the Body Mass Index, or BMI, which divides a person's weight (in kilograms) by their height (in meters) squared. Medically speaking, BMI scores break down as follows:

- BMI under 18.5 = underweight

- BMI 18.5 to <25 = healthy

- BMI 25 to <30 = overweight

- BMI 30 to <35 = obese (class 1)

- BMI 35 to <40 = obese (class 2)

- BMI 40 or higher = obese (class 3 - morbid)

BMI is not a perfect measure. In particular, it can sometimes give a "false positive" score to athletic individuals, whose high BMIs are due not to excess body fat, but to excess muscle. For example, extremely fit NFL quarterback Russell Wilson measured 5'11" tall and 215 pounds in 2016, which gave him a BMI of 30.0, or obese. NBA superstar and wellness enthusiast Lebron James had a BMI of 27.5 in 2012, which qualified as overweighta clear misdiagnosis. As a result of this inaccuracy, many medical experts are switching to waist-to-height ratio, or WHtR, which compares the circumference of a person's waist to their height. If the waist is more than half the height, (or more than 6/10 the height for those over 50), that person is obese. WHtR is considered much more accurate than BMI, but is also much newer. Over time, as it is adopted by more countries, WHtR could easily replace BMI as the de facto measure of a person's weight health.

Obesity by Country

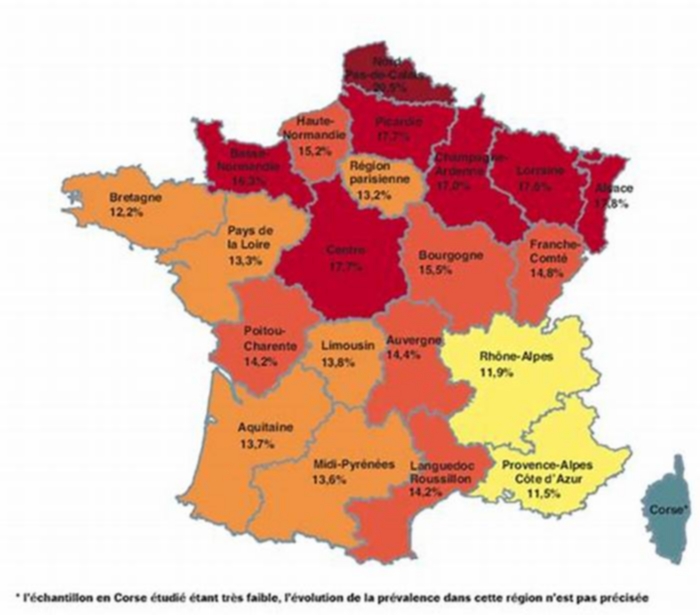

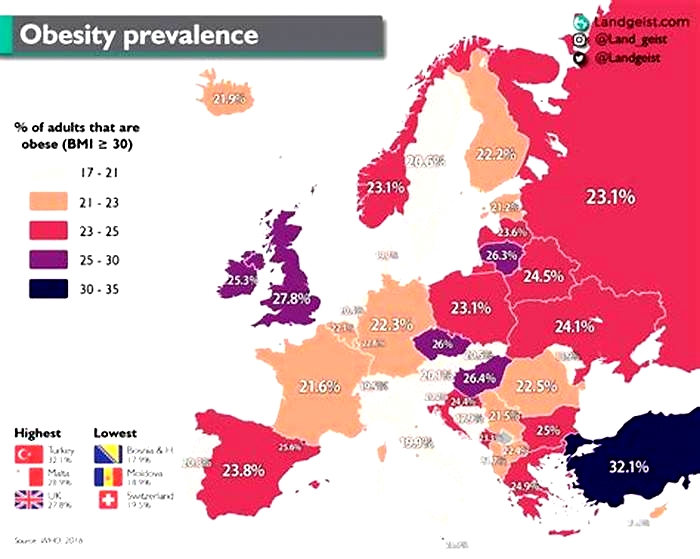

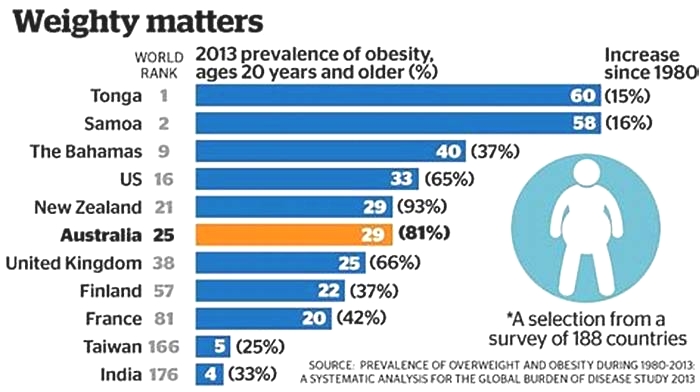

Obesity rates vary significantly by country as a result of different lifestyles and diets. There is no direct correlation between the obesity rate of a country and its economic status; however, wealthier countries tend to have more resources to implement programs, campaigns, and initiatives to raise awareness and education people about what they are consuming. These are among the healthiest countries globally. Some regions of the world, such as the South Pacific, have seen alarming increases in obesity rates within the past five years. Some governments, such as the United States government, have launched campaigns in recent years to promote healthier lifestyles and being active.

The 10 Most Obese Countries in the World

The most obese country by average BMI is the Cook Islands, which has an average BMI of 32.9. Nauru follows with 32.5, then Niue with 32.4. Samoa and Tonga both have average BMIs of 32.2. Finishing the top ten most obese countries are Tuvalu (30.8), Kiribati (30.1), Saint Lucia (30.0), Micornesia (29.7), and Egypt (29.6). What eight of these countries have in common is being located in the South Pacific. When looking at the percentage of obese adults, the list looks a little different. The most obese country by percentage of obese adults is Nauru, with 61% of adults falling in the obese category. Cook Islands fllows with 55.9%, and Palau just under that at 55.3%. Three other countries have adult populations that are over 50% obese: the Marshall Islands (52.9%), Tuvalu (51.6%), and Niue (50%). Finishing the list are Tonga (48.2%), Samoa (47.3%), Kiribati (46.0%), Micronesia (45.8%). The Pacific island nations appear prominently, with Saint Lucia and Egypt serving as the only non-Oceania countries on either list. Type 2-diabetes is a large concern among the people of many of these countries. Multiple theories exist as to why this particular region is so susceptible to obesity, including the growth of unhealthy fast food, the rise of frying as a means of food preparation, and a possible genetic predisposition toward higher BMIs.

The United States has the 12th highest obesity rate in the world at 36.2%. Obesity rates vary significantly between states](/state-rankings/obesity-rate-by-state), ranging from 23% to 38.10%. This is due to the same dietary, environmental, and cultural factors that cause variations between countries. Diet is primarily to blame, with Americans receiving mixed messages about what they should be eating and how much of it. Faced with mouth-watering advertisements served alongside campaigns promoting daily physical activity and proper nutrition, many Americans opt for fast, cheap, and filling options such as processed packaged food, fast food, and larger portions. This often leads to a diet rich in fat, calories, and sodium (the "butter, sugar, salt" trifecta) and low in vitamins and nutrients.

Top 10 Least Obese Countries in the World

When looking at average BMI, three countries tie for the least obese country in the world, with an average BMI of 21.1: Madagascar, Eritrea, and Ethiopia. Five other countries have average BMIs under 22: Timor-Leste (21.3), Burundi (21.6), Japan (21.8), China (21.9) and India (21.9). Bangladesh (22.0) and Burkina Faso (22.1) finish the list. Japan's presence here is perhaps unsurprising given that the national dietwhich emphasizes seafood, freshness, modest portions, and minimal added sugar or dairy fatis a very healthy approach (as evidenced by the fact that Japanese life expectancy is among the highest on Earth). However, many of the other countries on this list struggle with famine and povertywhich is the wrong way to achieve a low BMI.