Why are so many Labradors overweight

Why are so many of our pets overweight?

When I looked at my appointment book for the day, I thought something must be wrong. Someone who worked in the fitness industry was bringing his cat in to the Tufts Obesity Clinic for Animals. Did he confuse us for a different kind of weight management clinic? Is he looking to get muscle on his cat or maybe kitty protein shakes?

I was utterly surprised when I called for my appointment in the lobby and an athletic man stood up with an almost 20-pound cat! I asked if I could speak bluntly with him. Why does someone who clearly knows a lot about keeping healthy need to bring his cat to a veterinary nutritionist? What would he say if the cat was one of the people he helps to keep fit every day? Our conversation then went something like this

"Well, I'd tell her, suck it up, buttercup. Do some kitty pushups and no more treats!"

"Well, I have to ask, then, what's stopping you from doing this with your cat?"

With a worried look of guilt on his face, he replied, "Well, Dr. Linder, I mean she meows at me"

This was the moment I realized that I was treating pet obesity all wrong. I needed to focus less on the pet and more on the relationship between people and their pets. That's what's literally cutting the lives short of the dogs and cats we love so much.

An obese pet isn't a happy pet

As with humans, obesity in pets is at epidemic proportions. Over half of the dogs and cats around the globe battle the bulge.

While overweight pets may not face the same social stigma as humans, medical and emotional damage is being done all the same. Obesity in animals can cause complications in almost every system in the body, with conditions ranging from diabetes to osteoarthritis.

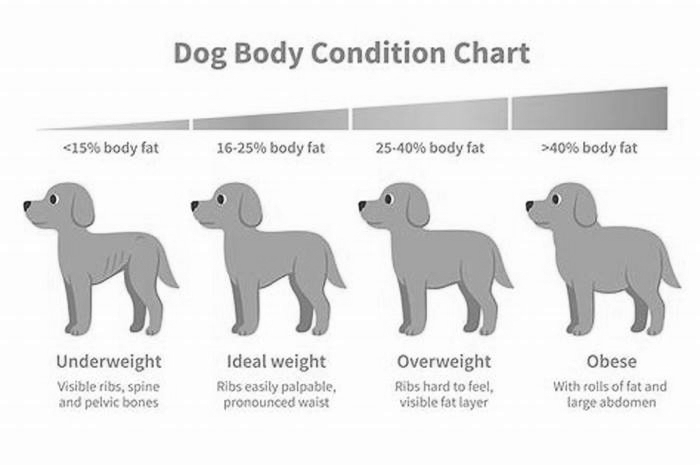

Owners often say they don't care if their pet is "fat" there's just more of them to love! It's my job to then let them know there's less time to provide that love. A landmark lifespan study showed Labradors who were 10-20 percent overweight not even obese, which is typically defined as greater than 20 percent lived a median 1.8 years shorter than their trim ideal weight counterparts.

Another study shows that obesity indeed has emotional consequences for pets. Overweight pets have worse scores in vitality, quality of life, pain and emotional disturbance. However, the good news is those values can improve with weight loss.

Furthermore, humans struggle to succeed even in the best conditions and so do pets. In one study, dogs on a weight-loss program were only successful 63 percent of the time.

Showing love through food

So where exactly is the problem? Are foods too high in calories? Are pets not getting enough exercise? Is it genetics? Or do we just fall for those puppy dog eyes and overfeed them because they have in fact trained us (not the other way around!)? From my experience at the pet obesity clinic, I can tell you it's a bit of all of the above.

It seems veterinarians and pet owners may be a little behind the curve compared to our human counterparts. Studies show that it doesn't really matter what approach to weight loss most humans take as long as they stick to it. But many in veterinary medicine focus more on traditional diet and exercise plans, and less on adherence or the reason these pets may have become obese to begin with. (This should be easy, right? The dogs aren't opening the fridge door themselves!)

However, the field is starting to understand that pet obesity is much more about the human-animal bond than the food bowl. In 2014, I worked among a group of fellow pet obesity experts organized by the American Animal Hospital Association to publish new weight management guidelines, recognizing that the human-animal bond needs to be addressed. Is the pet owner ready to make changes and overcome challenges that might slow down their pet's weight loss?

One interesting editorial review compared parenting styles to pet ownership. As pet owners, we treat our cats and dogs more like family members. There's a deeper emotional and psychological bond that was not as common when the family dog was just the family dog. If vets can spot an overindulgent pet parent, perhaps we can help them develop strategies to avoid expressing love through food.

A healthier relationship

Managing obesity in pets will require veterinarians, physicians and psychologists to work together.

Many veterinary schools and hospitals now employ social workers who help veterinarians understand the social aspect of the human-animal bond and how it impacts the pet's care. For example, a dog owner who has lost a spouse and shares an ice cream treat every night with their dog may be trying to replace a tradition they used to cherish with their significant other. A social worker with a psychology background could help prepare a plan that respects the owner's bond with their pet without negatively impacting the pet's health.

At our obesity clinic at Tufts, physicians, nutritionists and veterinarians are working together to develop joint pet and pet owner weight-loss programs. We want to put together a healthy physical activity program, so pet owners and their dogs can both improve their health and strengthen their bond. We also created a pet owner education website with additional strategies for weight loss and pet nutrition.

Programs that strengthen and support the human-animal bond without adding calories will be critical to preserve the loving relationship that is the reason why we adopt our pets, but also keep us from literally loving them to death by overfeeding. Hopefully, we can start to chip away at the notion that "food is love" for our pets.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Citation:Why are so many of our pets overweight? (2017, December 27)retrieved 26 April 2024from https://phys.org/news/2017-12-pets-overweight.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.

Genetic variant may help explain why Labradors are prone to obesity

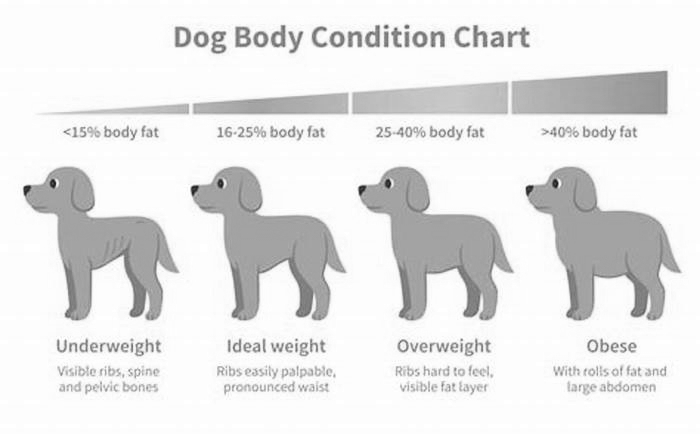

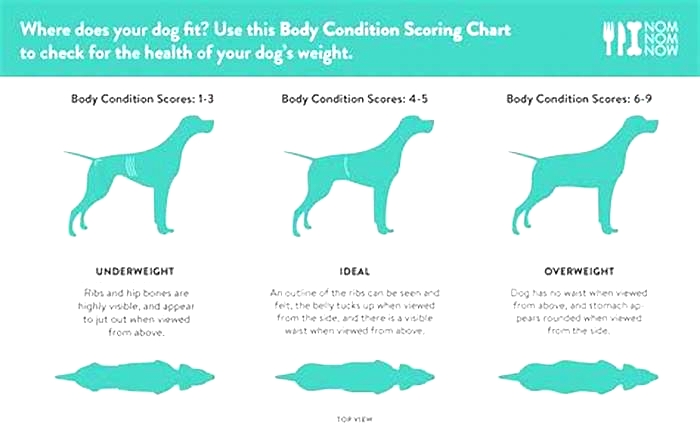

In developed countries, between one and two in three dogs (34-59%) is overweight, a condition associated with reduced lifespan, mobility problems, diabetes, cancer and heart disease, as it is in humans. In fact, the increase in levels of obesity in dogs mirrors that in humans, implicating factors such as reduced exercise and ready access to high calorie food factors. However, despite the fact that dog owners control their pets diet and exercise, some breeds of dog are more susceptible to obesity than others, suggesting the influence of genetic factors. Labradors are the most common breed of dog in the UK, USA and many other countries worldwide and the breed is known as being particularly obesity-prone.In a study published today in the journal Cell Metabolism, an international team led by researchers at the Wellcome Trust-Medical Research Council Institute of Metabolic Science, University of Cambridge, report a study of 310 pet and assistance dog Labradors. Independent veterinary professionals weighed the dogs and assessed their body condition score, and the scientists searched for variants of three candidate obesity-related genes. The team also assessed food motivation using a questionnaire in which owners reported their dogs behavior related to food.The researchers found that a variant of one gene in particular, known as POMC, was strongly associated with weight, obesity and appetite in Labradors and flat coat retrievers. Around one in four (23%) Labradors is thought to carry at least one copy of the variant. In both breeds, for each copy of the gene carried, the dog was on average 1.9kg heavier, an effect size particularly notable given the extent to which owners, rather than the dogs themselves, control the amount of food and exercise their dogs receive.This is a common genetic variant in Labradors and has a significant effect on those dogs that carry it, so it is likely that this helps explain why Labradors are more prone to being overweight in comparison to other breeds, explains first author Dr Eleanor Raffan from the University of Cambridge. However, its not a straightforward picture as the variant is even more common among flat coat retrievers, a breed not previously flagged as being prone to obesity.The gene affected is known to be important in regulating how the brain recognises hunger and the feeling of being full after a meal. People who live with Labradors often say they are obsessed by food, and that would fit with what we know about this genetic change, says Dr Raffan.Senior co-author Dr Giles Yeo adds: Labradors make particularly successful working and pet dogs because they are loyal, intelligent and eager to please, but importantly, they are also relatively easy to train. Food is often used as a reward during training, and carrying this variant may make dogs more motivated to work for a titbit.But its a double-edged sword carrying the variant may make them more trainable, but it also makes them susceptible to obesity. This is something owners will need to be aware of so they can actively manage their dogs weight.The researchers believe that a better understanding of the mechanisms behind the POMC gene, which is also found in humans, might have implications for the health of both Labradors and human.Professor Stephen ORahilly, Co-Director of the Wellcome Trust-Medical Research Council Institute of Metabolic Science, says: Common genetic variants affecting the POMC gene are associated with human body weight and there are even some rare obese people who lack a very similar part of the POMC gene to the one that is missing in the dogs. So further research in these obese Labradors may not only help the wellbeing of companion animals but also have important lessons for human health.The research was funded by the Wellcome Trust, the Medical Research Council and the Dogs Trust.ReferenceRaffan, E et al. A deletion in the canine POMC gene is associated with weight and appetite in obesity prone Labrador retriever dogs. Cell Metabolism; 3 May 2016; DOI: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.04.012

Why people become overweight

Everyone knows some people who can eat ice cream, cake, and whatever else they want and still not gain weight. At the other extreme are people who seem to gain weight no matter how little they eat. Why? What are the causes of obesity? What allows one person to remain thin without effort but demands that another struggle to avoid gaining weight or regaining the pounds he or she has lost previously?

On a very simple level, your weight depends on the number of calories you consume, how many of those calories you store, and how many you burn up. But each of these factors is influenced by a combination of genes and environment. Both can affect your physiology (such as how fast you burn calories) as well as your behavior (the types of foods you choose to eat, for instance). The interplay between all these factors begins at the moment of your conception and continues throughout your life.

The calorie equation

The balance of calories stored and burned depends on your genetic makeup, your level of physical activity, and your resting energy expenditure (the number of calories your body burns while at rest). If you consistently burn all of the calories that you consume in the course of a day, you will maintain your weight. If you consume more energy (calories) than you expend, you will gain weight.

Excess calories are stored throughout your body as fat. Your body stores this fat within specialized fat cells (adipose tissue) either by enlarging fat cells, which are always present in the body, or by creating more of them. If you decrease your food intake and consume fewer calories than you burn up, or if you exercise more and burn up more calories, your body will reduce some of your fat stores. When this happens, fat cells shrink, along with your waistline.

Genetic influences

To date, more than 400 different genes have been implicated in the causes of overweight or obesity, although only a handful appear to be major players. Genes contribute to the causes of obesity in many ways, by affecting appetite, satiety (the sense of fullness), metabolism, food cravings, body-fat distribution, and the tendency to use eating as a way to cope with stress.

The strength of the genetic influence on weight disorders varies quite a bit from person to person. Research suggests that for some people, genes account for just 25% of the predisposition to be overweight, while for others the genetic influence is as high as 70% to 80%. Having a rough idea of how large a role genes play in your weight may be helpful in terms of treating your weight problems.

How much of your weight depends on your genes?

Genes are probably a significant contributor to your obesity if you have most or all of the following characteristics:

- You have been overweight for much of your life.

- One or both of your parents or several other blood relatives are significantly overweight. If both of your parents have obesity, your likelihood of developing obesity is as high as 80%.

- You can't lose weight even when you increase your physical activity and stick to a low-calorie diet for many months.

Genes are probably a lower contributor for you if you have most or all of the following characteristics:

- You are strongly influenced by the availability of food.

- You are moderately overweight, but you can lose weight when you follow a reasonable diet and exercise program.

- You regain lost weight during the holiday season, after changing your eating or exercise habits, or at times when you experience psychological or social problems.

These circumstances suggest that you have a genetic predisposition to be heavy, but it's not so great that you can't overcome it with some effort.

At the other end of the spectrum, you can assume that your genetic predisposition to obesity is modest if your weight is normal and doesn't increase even when you regularly indulge in high-calorie foods and rarely exercise.

People with only a moderate genetic predisposition to be overweight have a good chance of losing weight on their own by eating fewer calories and getting more vigorous exercise more often. These people are more likely to be able to maintain this lower weight.

What are thrifty genes?

When the prey escaped or the crops failed, how did our ancestors survive? Those who could store body fat to live off during the lean times lived, and those who couldn't, perished. This evolutionary adaptation explains why most modern humans about 85% of us carry so-called thrifty genes, which help us conserve energy and store fat. Today, of course, these thrifty genes are a curse rather than a blessing. Not only is food readily available to us nearly around the clock, we don't even have to hunt or harvest it!

In contrast, people with a strong genetic predisposition to obesity may not be able to lose weight with the usual forms of diet and exercise therapy. Even if they lose weight, they are less likely to maintain the weight loss. For people with a very strong genetic predisposition, sheer willpower is ineffective in counteracting their tendency to be overweight. Typically, these people can maintain weight loss only under a doctor's guidance. They are also the most likely to require weight-loss drugs or surgery.

The prevalence of obesity among adults in the United States has been rising since the 1970s. Genes alone cannot possibly explain such a rapid rise. Although the genetic predisposition to be overweight varies widely from person to person, the rise in body mass index appears to be nearly universal, cutting across all demographic groups. These findings underscore the importance of changes in our environment that contribute to the epidemic of overweight and obesity.

Environmental causes of obesity

Genetic factors are the forces inside you that help you gain weight and stay overweight; environmental factors are the outside forces that contribute to these problems. They encompass anything in our environment that makes us more likely to eat too much or exercise too little. Taken together, experts think that environmental factors are the driving force for the causes of obesity and its dramatic rise.

Environmental influences come into play very early, even before you're born. Researchers sometimes call these in-utero exposures "fetal programming." Babies of mothers who smoked during pregnancy are more likely to become overweight than those whose mothers didn't smoke. The same is true for babies born to mothers who had diabetes. Researchers believe these conditions may somehow alter the growing baby's metabolism in ways that show up later in life.

After birth, babies who are breast-fed for more than three months are less likely to have obesity as adolescents compared with infants who are breast-fed for less than three months.

Childhood habits often stick with people for the rest of their lives. Kids who drink sugary sodas and eat high-calorie, processed foods develop a taste for these products and continue eating them as adults, which tends to promote weight gain. Likewise, kids who watch television and play video games instead of being active may be programming themselves for a sedentary future.

Many features of modern life promote weight gain. In short, today's "obesogenic" environment encourages us to eat more and exercise less. And there's growing evidence that broader aspects of the way we live such as how much we sleep, our stress levels, and other psychological factors can affect weight as well.

The food factor as one of the causes of obesity

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Americans are eating more calories on average than they did in the 1970s. Between 1971 and 2000, the average man added 168 calories to his daily fare, while the average woman added 335 calories a day. What's driving this trend? Experts say it's a combination of increased availability, bigger portions, and more high-calorie foods.

Practically everywhere we go shopping centers, sports stadiums, movie theaters food is readily available. You can buy snacks or meals at roadside rest stops, 24-hour convenience stores, even gyms and health clubs. Americans are spending far more on foods eaten out of the home: In 1970, we spent 27% of our food budget on away-from-home food; by 2006, that percentage had risen to 46%.

In the 1950s, fast-food restaurants offered one portion size. Today, portion sizes have ballooned, a trend that has spilled over into many other foods, from cookies and popcorn to sandwiches and steaks. A typical serving of French fries from McDonald's contains three times more calories than when the franchise began. A single "super-sized" meal may contain 1,5002,000 calories all the calories that most people need for an entire day. And research shows that people will often eat what's in front of them, even if they're already full. Not surprisingly, we're also eating more high-calorie foods (especially salty snacks, soft drinks, and pizza), which are much more readily available than lower-calorie choices like salads and whole fruits. Fat isn't necessarily the problem; in fact, research shows that the fat content of our diet has actually gone down since the early 1980s. But many low-fat foods are very high in calories because they contain large amounts of sugar to improve their taste and palatability. In fact, many low-fat foods are actually higher in calories than foods that are not low fat.

The exercise equation

The government's current recommendations for exercise call for an hour of moderate to vigorous exercise a day. But fewer than 25% of Americans meet that goal.

Our daily lives don't offer many opportunities for activity. Children don't exercise as much in school, often because of cutbacks in physical education classes. Many people drive to work and spend much of the day sitting at a computer terminal. Because we work long hours, we have trouble finding the time to go to the gym, play a sport, or exercise in other ways.

Instead of walking to local shops and toting shopping bags, we drive to one-stop megastores, where we park close to the entrance, wheel our purchases in a shopping cart, and drive home. The widespread use of vacuum cleaners, dishwashers, leaf blowers, and a host of other appliances takes nearly all the physical effort out of daily chores and can contribute as one of the causes of obesity.

The trouble with TV: Sedentary snacking

The average American watches about four hours of television per day, a habit that's been linked to overweight or obesity in a number of studies. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, a long-term study monitoring the health of American adults, revealed that people with overweight and obesity spend more time watching television and playing video games than people of normal weight. Watching television more than two hours a day also raises the risk of overweight in children, even in those as young as three years old.

Part of the problem may be that people are watching television instead of exercising or doing other activities that burn more calories (watching TV burns only slightly more calories than sleeping, and less than other sedentary pursuits such as sewing or reading). But food advertisements also may play a significant role. The average hour-long TV show features about 11 food and beverage commercials, which encourage people to eat. And studies show that eating food in front of the TV stimulates people to eat more calories, and particularly more calories from fat. In fact, a study that limited the amount of TV kids watched demonstrated that this practice helped them lose weight but not because they became more active when they weren't watching TV. The difference was that the children ate more snacks when they were watching television than when doing other activities, even sedentary ones.

Stress and related issues

Obesity experts now believe that a number of different aspects of American society may conspire to promote weight gain. Stress is a common thread intertwining these factors. For example, these days it's commonplace to work long hours and take shorter or less frequent vacations. In many families, both parents work, which makes it harder to find time for families to shop, prepare, and eat healthy foods together. Round-the-clock TV news means we hear more frequent reports of child abductions and random violent acts. This does more than increase stress levels; it also makes parents more reluctant to allow children to ride their bikes to the park to play. Parents end up driving kids to play dates and structured activities, which means less activity for the kids and more stress for parents. Time pressures whether for school, work, or family obligations often lead people to eat on the run and to sacrifice sleep, both of which can contribute to weight gain.

Some researchers also think that the very act of eating irregularly and on the run may be another one of the causes of obesity. Neurological evidence indicates that the brain's biological clock the pacemaker that controls numerous other daily rhythms in our bodies may also help to regulate hunger and satiety signals. Ideally, these signals should keep our weight steady. They should prompt us to eat when our body fat falls below a certain level or when we need more body fat (during pregnancy, for example), and they should tell us when we feel satiated and should stop eating. Close connections between the brain's pacemaker and the appetite control center in the hypothalamus suggest that hunger and satiety are affected by temporal cues. Irregular eating patterns may disrupt the effectiveness of these cues in a way that promotes obesity.

Similarly, research shows that the less you sleep, the more likely you are to gain weight. Lack of sufficient sleep tends to disrupt hormones that control hunger and appetite and could be another one of the causes of obesity. In a 2004 study of more than 1,000 volunteers, researchers found that people who slept less than eight hours a night had higher levels of body fat than those who slept more, and the people who slept the fewest hours weighed the most.

Stress and lack of sleep are closely connected to psychological well-being, which can also affect diet and appetite, as anyone who's ever gorged on cookies or potato chips when feeling anxious or sad can attest. Studies have demonstrated that some people eat more when affected by depression, anxiety, or other emotional disorders. In turn, overweight and obesity themselves can promote emotional disorders: If you repeatedly try to lose weight and fail, or if you succeed in losing weight only to gain it all back, the struggle can cause tremendous frustration over time, which can cause or worsen anxiety and depression. A cycle develops that leads to greater and greater obesity, associated with increasingly severe emotional difficulties.

To find weight loss solutions that can be tailored to your needs, buy the Harvard Special Health Report Lose Weight and Keep It Off.