Who has the worst obesity

Britain has one of the worst obesity rates in Europe. Why?

For years, Alice Ingmans favourite foods were takeaway curries, pizza, fried chicken, kebabs, and fish and chips. The 59-year-old gained weight steadily until one day she could not even fit into a size 20. She was 115kg and mortified.

At the beginning I thought, Oh, its because its a pencil skirt, says Ingman, from Cambridgeshire, calling it one of many excuses she had relied on to make herself feel better. But theres no getting away from it when a size 20 doesnt fit.

This was a wake-up call for her to change her diet. She joined a weight-loss group and started cooking meals from scratch for the first time in her life. She says she has maintained a weight of 60kg for five years since.

Ingmans back-to-basics approach worked for her. But the arrival of the weight-loss jab Wegovy to the NHS last month has been heralded as a game-changer in the fight against obesity by using a hormone to suppress appetite.

While health experts and charities welcome the development of new drugs, they argue that a broader conversation is needed about the UKs approach to food, and want industry and the government to take more definitive action.

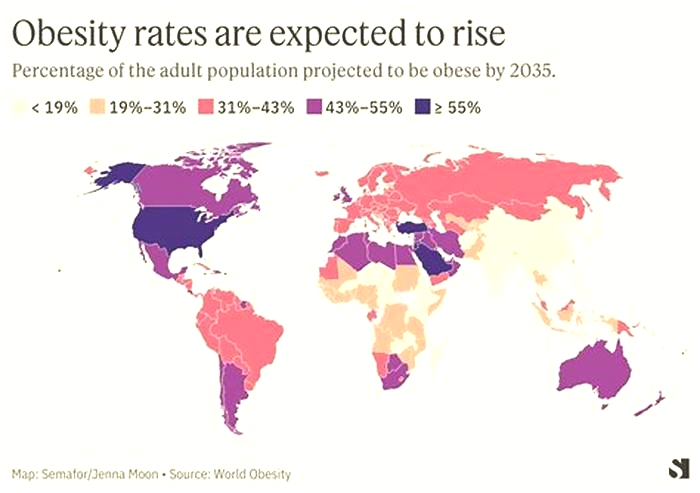

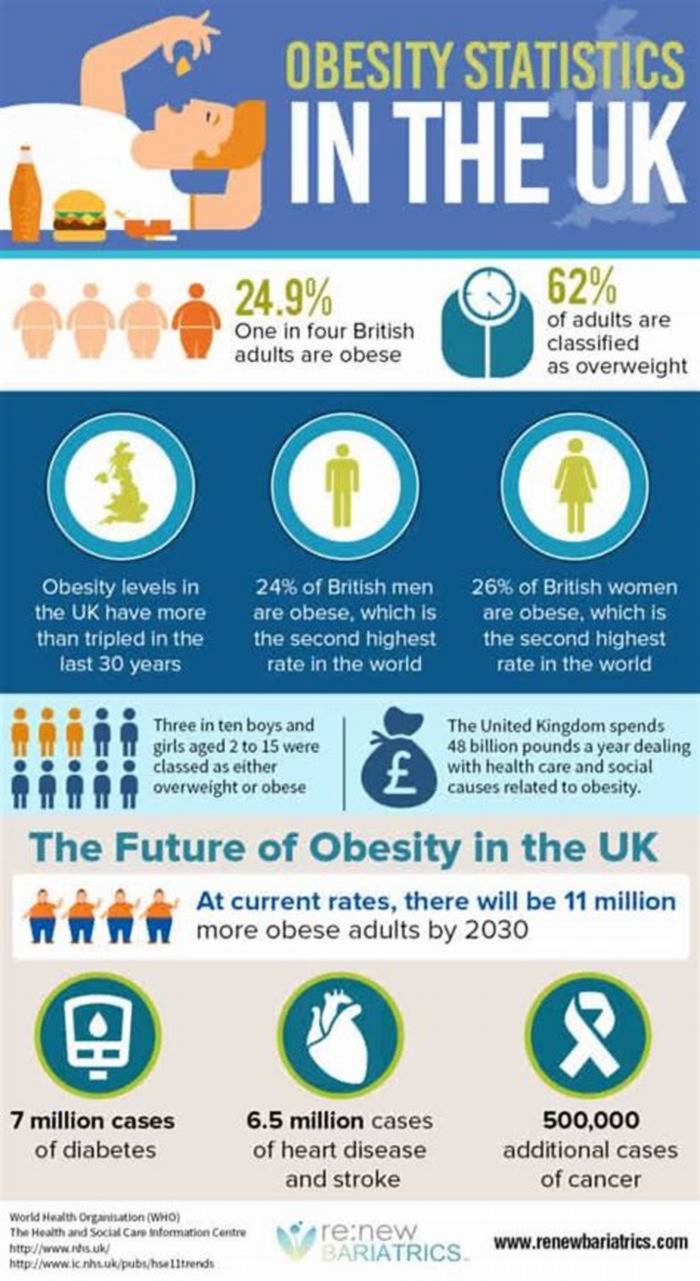

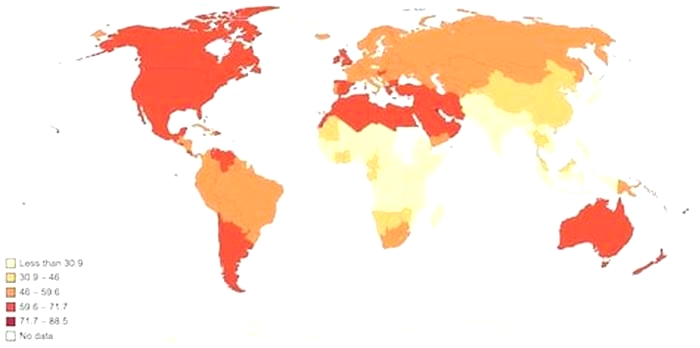

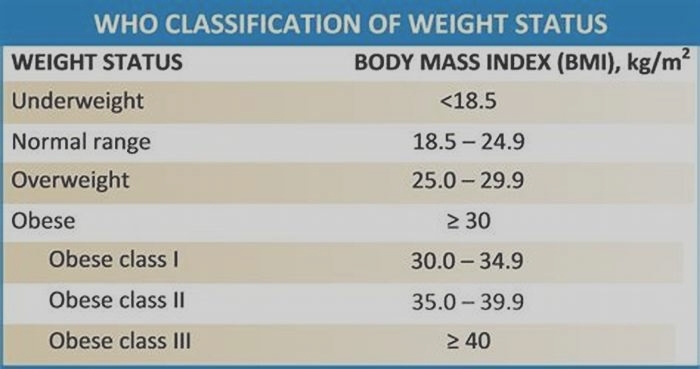

Obesity, defined as having a body mass index equal to or greater than 30, is one of the most serious public health crises around the world. The UK, where 27.8 per cent of population is obese, has one of the highest rates in Europe.

An increased reliance on cheap, ultra-processed food, which accounts for 57 per cent of what Britons eat according to a 2019 study conducted by researchers at the University of So Paulo, suggests that the health crisis is unlikely to change anytime soon without intervention, argue campaigners.

There is a very strange imbalance [in] that the foods that are most appealing, affordable and available just happen to be those that are the least healthy, says Katharine Jenner, nutritionist and director of the Obesity Health Alliance, a coalition of more than 50 health organisations.

The food system in this country is broken, she adds. Its not serving society nor our health system, and certainly not individuals.

The poverty health tax

The effects of obesity are widespread.

It causes severe health conditions including heart disease, diabetes and cancer, costing about 6.5bn in the UK every year, according to the NHS. Globally, the World Health Organization says at least 2.8mn people die each year as a result of being overweight or obese.

Many health professionals point to the severe dietary changes over the past 50 years. Data of family eating habits shows that more of us are consuming less healthy food, usually high in fat, sugar or salt. The average consumption of takeaway chicken has increased by 613 per cent from 1974, ready meals and convenience meat products by 549 per cent and crisps and potato snacks by 226 per cent.

Meanwhile, households buy less non-processed food. Consumption of beef and veal has decreased by 55 per cent, fresh cabbages by 67 per cent and fresh apples by 44 per cent.

Health experts say the affordability of processed foods is a significant driver of these dietary patterns. Fruits and vegetables are the most expensive category in the governments recommended Eatwell Guide, costing on average 11.79 per 1,000kcal, compared with food and drink high in fat and sugar costing just 5.82 per 1,000kcal, according to the Food Foundation, a UK charity.

This is partly because fruits and vegetables have a lower energy density, fewer calories per gramme, than processed foods. But this price disparity explains why obesity is more prominent among the most vulnerable households.

The Kings Fund, through its analysis of the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities data, last year found that inequalities in obesity prevalence between the least and most deprived areas widened to nearly 18 points in 2020.

Poverty is a driver of poor eating behaviours, because choice is not there, says Paul Gately, professor of exercise and obesity at Leeds Beckett University. Food retailers and the food industry would be able to fight against obesity by making healthy products more affordable.

There are other changes that could be beneficial. Unhealthy food is often heavily advertised. A third of food and soft drink advertising spend in the UK goes towards confectionery, snacks, desserts and soft drinks, compared with only 1 per cent for fruit and vegetables, the Food Foundation has found.

Many people think that obesity levels are very much about individual responsibility, says Shona Goudie, the charitys policy and advocacy manager. But what we can see from [the research] is actually that the system is not set up to help us eat well.

Decades of policy

The UK government set its first strategy focused on reducing obesity in 1992 and other efforts have followed with mixed success.

One of its key policies was a soft drinks levy introduced in 2018 to push manufacturers to add less sugar to their products. This step may have prevented more than 5,000 cases of obesity every year among girls in their final year of primary school, according to an analysis from the University of Cambridge.

Last October, the government barred large stores from placing items high in fat, sugar or salt in prominent positions, but health campaigners say too many of its obesity policies lack urgency. I think its very clear that the government hasnt gone far enough to tackle obesity, says Goudie.

Henry Dimbleby, co-founder of fast-food restaurant chain Leon who quit his role as a UK government adviser in March, wrote in his book Ravenous, published this year, that the governments strategy was far too scant, fragmented, and cautious to meet the scale of the problem. He recommended taxing salt and sugar to encourage manufacturers to produce healthier foods, a proposal rejected by ministers.

There have been other setbacks. The government announced in June that rules banning multi-buy deals on food and drinks high in salt and sugar, such as buy one, get one free, will be delayed until October 2025. The decision, taken amid a cost of living crisis, came after the policy had already been delayed once before. The government has also pushed back proposed restrictions on unhealthy food adverts.

Companies producing healthier alternatives of sweets and snacks, especially small businesses, had been counting on receiving more funding from investors off the back of the legislation.

The more [the implementation] got delayed, the less interested investors became. By the time [the restrictions on product placement] happened, the spark had gone and lots of those small businesses hadnt been able to raise money and died, says Louis Bedwell, managing director at venture capital firm Mission Ventures.

The government is also scaling back public health grants to support services such as weight management. Data compiled by the Health Foundation shows that public-health spending on adult obesity by local authorities this year is estimated at 132mn, down 27 per cent from 2015. Although the government in March 2021 announced 100mn of new funding a large part of which was invested in weight-management services through the NHS and local authorities it was scrapped the year after.

Carolyn Pallister, the head of nutrition, research and health at Slimming World which helped Ingman lose weight says choosing healthy food is not just about how and where products are placed or advertised. What we see from members is that people need support to be able to [make better choices], she says, adding that theres a real kind of postcode lottery based on where you live.

The Department of Health and Social Care says the government continues to take action to help more people make healthier choices and tackle obesity.

The launch of Wegovy in the UK has also paved the future of weight management in England, it adds.

Ingman, who jokes that she is now half the person she was, credits the first cookbook she bought from her slimming club with teaching her what a healthy balanced plate should look like. That was a big change, she explains, for someone who previously thought it was quite acceptable to pick up something that you pop in the microwave.

She is confident that she has the skills she needs to maintain a healthier weight: Its definitely a way of life for me now.

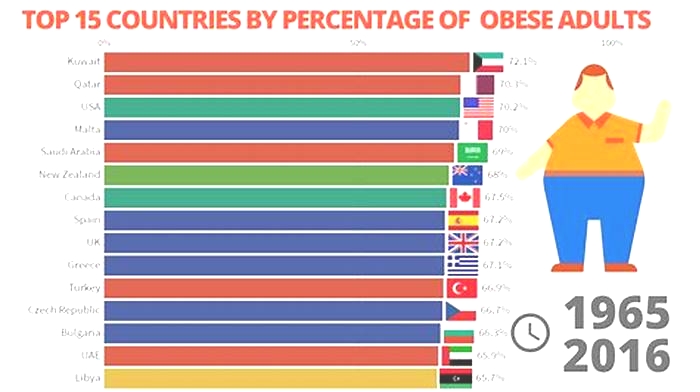

List of countries by obesity rate

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (October 2023) |

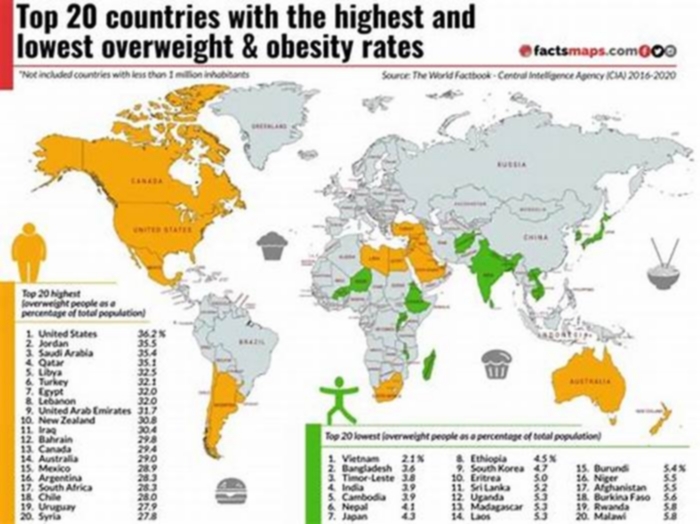

This is a list of countries ranked by the proportion of the population that is obese. The data, barring the United States, is derived from The World Factbook authored by the Central Intelligence Agency,[1] which gives the adult prevalence rate for obesity, defined as "the percent of a country's population considered to be obese". Data for U.S. obesity prevalence is derived from CDC data, recorded through the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) in March 2017 2020.[2]

Related[edit]

References[edit]

UK is most obese country in western Europe, OECD finds

The UK is the most obese country in western Europe, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Its annual Health at a Glance report, published on Friday, shows that 26.9% of the UK population had a body mass index of 30 and above, the official definition of obesity, in 2015. Only five of the OECDs 35 member states had higher levels of obesity, with four outside Europe and one in eastern Europe.

The OECDs report, which says obesity in the UK has increased by 92% since the 1990s, illustrates the scale of the public health challenge, with fears it could bankrupt the NHS.

Tam Fry, chair of the National Obesity Forum, said: One could weep over the figures, the result of successive governments who have, for the last 30 years, done next to nothing to tackle obesity.

Even today, we have only a pathetic attempt by Theresa Mays administration to get serious about reducing the numbers and avoiding an official estimate that more than 50% of the UK will be obese by 2050. Ten years ago, a government department report stated that the nation was sleepwalking into obesity but no minister, either then or since, has woken up to the fact.

The government was heavily criticised when it launched its childhood obesity strategy last year for its reliance on voluntary action by the food and drink industry and lack of restrictions on junk food marketing and advertising.

Along with smoking, obesity is one of the two main drivers behind the biggest killers of the modern world: cancers, heart attacks, strokes and diabetes.

The UK has the 11th highest cancer mortality rate (221.9 deaths per 100,000 people), according to the OECD. But the proportion of adults with diabetes in the UK (4.7%) was one of the lowest, bettered only by Lithuania, Estonia and Ireland.

The report comes the day after official figures were published showing a record number of caesareans (28% of all births) in English hospitals in 2016-17, up 11% in five years. The increase was partly attributed to rising obesity levels, accompanied as it was by statistics showing one in five women pregnant women have a BMI greater than 30.

Last month, the World Obesity Forum predicted that unless effective action is taken, the cost of treating ill health caused by obesity in the UK will rise from $19bn (14bn) to $31bn per year in 2025.

The US has the highest level of obesity (38%), according to the OECD, followed by Mexico, New Zealand, Hungary and Australia.

Dr Alison Tedstone, chief nutritionist at Public Health England, said: Most countries are facing rising levels of obesity, putting pressure on health and social care systems. While England has the worst rates of adult obesity in western Europe, our plans to tackle this are among the most ambitious.

Were working with industry to make food healthier, weve produced guidance for councils on planning healthier towns and were delivering campaigns encouraging people to choose healthier food and lead healthier lives. Its taken many years for us to reach this point and change will not happen overnight.