What percent of Labradors are overweight

The Lab Results Are In: Genes Might Be to Blame for Retrievers Obesity

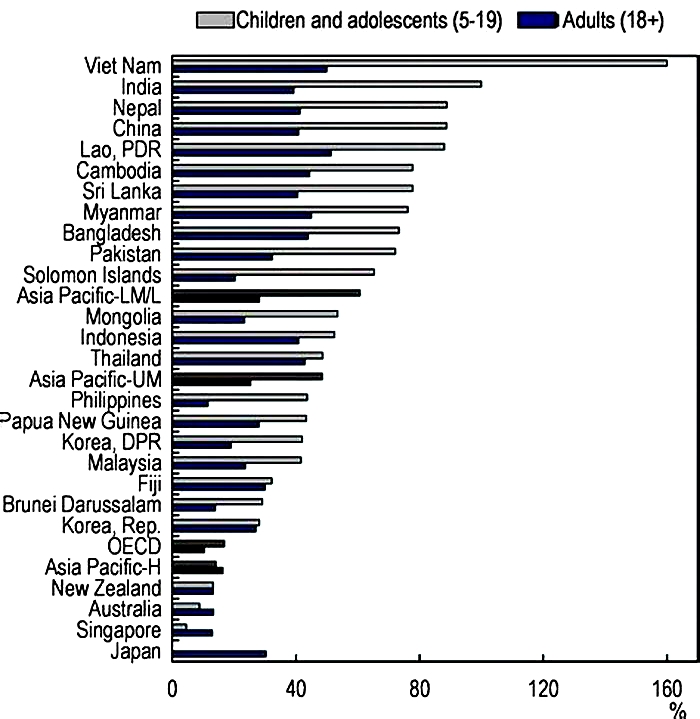

If youve ever had a Labrador retriever, you know about one of the breeds notable traits: an unrelenting appetite. The dogs will devour anything from socks to rocks, and given the chance, they can be prone to eat themselves into obesity. By one estimate, nearly 60 percent of all Labradors are overweight or obese.

In fact, the dubious honor of being named Britains fattest pet went to a 176-pound Labrador named Alfie, who was rather uncharitably described by one official as a massive blob with a leg at each corner.

Labradors have been caught sitting under an apple tree waiting for the fruit to fall and dragging their owners to a spot in the grass where they once found a discarded kebab years before.

Is it a character flaw? Are they incorrigible gluttons? Scientists at Cambridge University say no: Labradors cant help it; its in their genes.

Researchers studying 310 Labradors found that many of them were missing all or part of a gene known as POMC, which is known to regulate appetite in some species and to help sense how much fat the body has stored. Without it, the dogs dont know when theyve had enough, so they just keep eating and eating.

The POMC gene is also present in humans, and while cases are very rare, there are obese people with a similar gene deficiency.

The Labrador study reminds people that hard-wired biology explains why some animals, like affected Labradors and indeed some humans, are more prone to obesity than others, said Eleanor Raffan, the lead researcher. Their genes mean they are more hungry all the time.

Scientists have found the POMC mutation to be widespread in only one other dog breed: flat-coated retrievers, which are cousins to Labradors. Dr. Raffan said the scrambled POMC gene partly explains why Labradors are easy to train as service dogs: They will be willing to work harder for a treat, she said.

The scientists think the mutation arose in an earlier breed that Labradors are descended from, the St. Johns water dog, which fishermen used to retrieve nets from Newfoundlands icy waters.

The tendency to eat every food thats thrown your way would have been sensible under those conditions, Dr. Raffan said, but for a modern Labrador living as a pet, the mutation is no longer beneficial.

Canine obesity is on the rise generally, but for most dogs, rich food and lack of exercise are to blame, not genes.

Alfie grew so fat that it took four people to lift him. Breathing problems and bone damage prompted a crash diet, but he eventually had to be euthanized.

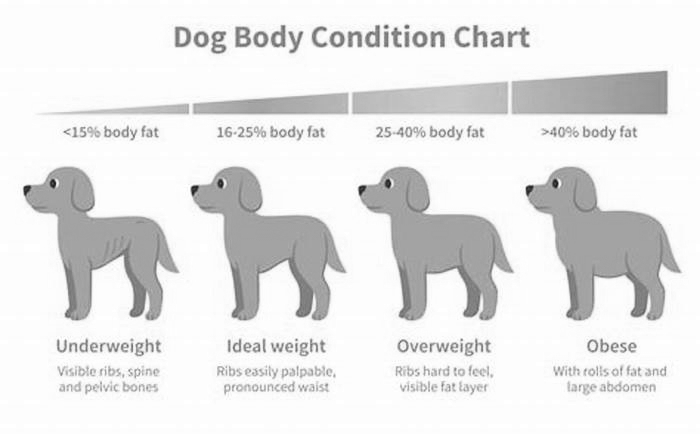

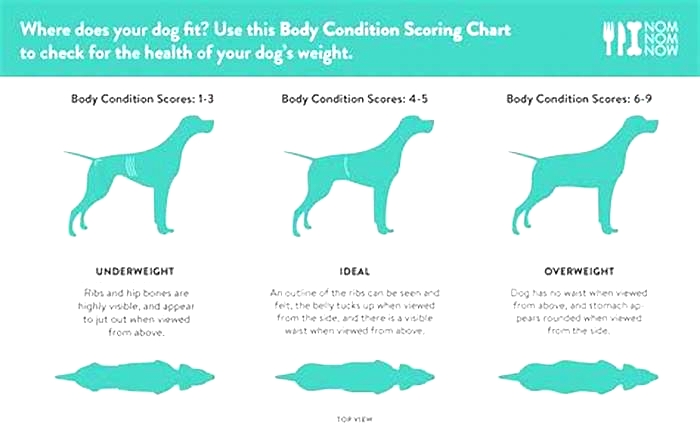

Evidence of longer life; a cohort of 39 labrador retrievers

A panel of veterinary and academic experts reviewed current available evidence on age at death for labradors and reached a consensus that their average/typical lifespan was 12years of age.1 A prospective cohort study that described the longevity of 39 pedigree adult neutered labradors, showed that 89.7percent lived to meet/exceed this typical lifespan. The study showed that maintenance of lean body mass and reduced accumulation of body fat were associated with attaining a longer than average lifespan while sex and age at neutering were not associated with longevity.1

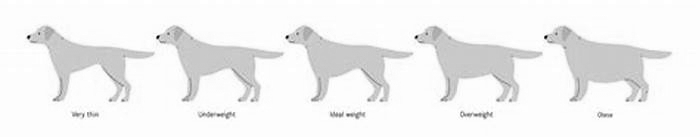

Thepresent cohort was derived from 31 litters via 19 known (7 unknown) dams and 12 known (7 unknown) sires enrolled in a prospective longitudinal study at a median age of 6.5years at the start of the study on July 16,2004. The last dog died on September 09,2015 at the age of 17.1years and the oldest dog, a male, reached 17.9years. The aim of this study was to compare the longevity of the present cohort fed to maintain a body condition score (BCS) between 2 and 4 on a 5-point scale to threehistorical comparison groups of pedigree labradors taken from previously published studies. The oldest of the oldlabradors from thepresent cohort could hold important clues on how to achieve healthy ageing. Further analysis of the cohorts clinical data is being undertaken with the objective to develop key strategies to increase the healthspan of dogs:

2004 UK Kennel Club (KC) survey dogs owned/kept by owners and breeders that died in the previous 10years (19942003).

21987 US Restricted group (n=24) fed 25percent less than a sex-matched and bodyweight-matched sibling pair to maintain a mean BCS between 4 and 5 on a 9-point scale; 48 puppies from seven litters with seven dams and two sires randomly assigned to feeding group at sixweeks of age, started on the study from eightweeks of age in 1987 and followed until death of all dogs in this pair-fed study.

351987 US Control group (n=24) initially fed ad libitum and then fed a restricted amount of food to prevent excessive weight gain.

Descriptive statistics are reported for age at death using median, minimum and maximum values. Median age at death was compared using Kruskal-Wallis analysis of variance with posthoc Dunns pairwise comparisons. After excluding 32 KC survey dogs that died at<3.5years of age, survival analysis was used to derive Kaplan-Meier product limit estimates of the survival functions with posthoc pairwise log rank tests and results are reported as median survival time (MST) with 95percent confidenceintervals. The proportions of dogs surviving to 12years and those alive at/beyond 15.6years of age were compared using cross-tabulations with 2 or Fishers exact tests. Level of significance for multiple comparisons was set at P<0.008using a Bonferroni correction as /k where /is 0.05 and k is the number of comparisons (six). A one-sample sign test was used to compare the median age at death of the longevity cohort to the average/typical lifespan of 12years for labradors.

The current cohort lived significantly longer than each of the historical comparison groups (P<0.0001). Survival analysis revealed significant differences in MSTs with thepresent cohort living longer than each of the other groups (P0.004, , ). Almost 90percent of thepresent cohort reached the average expected age of 12years for labradorretrievers while only 30percent of the US Control group achieved this (P<0.0001, ). Additionally, 28percent of the dogs in thepresent cohort reached/exceeded exceptional longevity, defined as being alive at/beyond 15.6years of age6 and this was significantly greater than any of the historical comparison groups (P<0.0001, ). Furthermore, the median age at death in thepresent cohort of 14.01years was significantly greater than the average/typicallifespan of 12years for labradorretrievers (P<0.0001). While age at neutering was not found to be linked to longevity in thepresent cohort, evaluation of the effect of age of neutering was not possible for the US dogs.5

Kaplan-Meier survival curves showing that the longevity study group lived significantly longer than the historical comparison groups.KC,Kennel Club.

TABLE 1

Descriptive statistics for age at death of the four groups of dogs and results of survival analysis

| Group | Descriptive statistics | Survival analysis | ||||

| N | Median age* | (Min-Max) | N | MST | (95%CI) | |

| Longevity study | 39 | 14.01a | (9.6817.90) | 39 | 14.01a | (13.18 to 14.77) |

| KC survey | 574 | 12.25b | (0.1719.00) | 542 | 12.58b | (12.17 to 12.92) |

| Restricted | 24 | 12.95b | (4.3014.56) | 24 | 12.90b | (12.38 to 13.40) |

| Control | 24 | 11.16b | (3.5013.29) | 24 | 11.14c | (10.80 to 11.99) |

TABLE 2

Numbers and proportions of dogs achieving a typical lifespan (average expected age of 12years) and an exceptional lifespan (age of15.6years)

| Group | Total dogs | Dogs reaching typical lifespan | Dogs reaching exceptional lifespan | ||||

| N | n | %* | 95%CI | n | % | 95%CI | |

| Longevity study | 39 | 35 | 89.7a | 74.8 to 96.7 | 11 | 28.20a | 15.6 to 45.1 |

| KC survey | 574 | 302 | 52.61ab | 48.4 to 56.8 | 24 | 4.18b | 2.8 to 6.3 |

| Restricted | 24 | 17 | 70.83ab | 48.8 to 86.6 | 0 | 0b | NA |

| Control | 24 | 7 | 29.16b | 13.4 to 51.3 | 0 | 0b | NA |

In spite of being 16 yearsand 17years of age, the last five dogs in thepresent cohort continued to be full of life, active, social and highly engaged with their animal welfare specialists and social groups. This suggests that the dogs experienced an increase in healthspan and not only in the actual years lived.

The dogs in thepresent cohort were more closely related than the dogs in the UK KC study but less closely related than the dogs in the US sibling-matched study and this suggests that while genetics is important, it is unlikely to be the primary driver of longevity. The environmental conditions that the dogs in thepresent cohort experienced were similar to those of the dogs in the US study while the dogs in the KC study were dogs kept by owners belonging to a UK breed club. There are likely to be differences in the living conditions experienced by the different groups of dogs that may have affected longevity. However, the reduced variation and fewer changes over time in management factors of thepresent cohort provided an opportunity to evaluate lifespan while controlling for the potential confounding impact of such variables.

The results of this study showed that thepresent cohort lived significantly longer than previously studied labradors and had a greater than expected proportion living well beyond that of the expected breed lifespan, despite the limitations of using historical comparison groups and the fact that all of these groups of dogs are inherently biased. These 39 labradors experienced a combination of a high quality plane of nutrition with appropriate husbandry and healthcare. Increased understanding and control of the ageing process provides an opportunity to estimate the impact of the longevity dividend. For humanbeings this is defined as the social, economic and health bonuses for both individuals and populations that accrue as a results of medical interventions to slow the rate of ageing.7 The importance of the oldest of the old dogs as reported here is that they can provide a model system for exploring the longevity dividend in humanbeings as well as dogs.8

The Real Reason Your Lab Is Fat

When your dog looks up at you hopefully with big, sad eyes, begging for a treat, it can be hard to say no in spite of your best intentions for restricting your pet to a healthier diet.

And one dog breed tests their owners more frequently, with more persistent begging than other breeds, according to a new study.

Labrador retrievers were found to be more inclined than other dog breeds to beg for treats, and to generally engage in behaviors related to getting more food. And the reason lies in their DNA, researchers found. [The 10 Most Popular Dog Breeds]

The study's lead author, Eleanor Raffan a veterinary surgeon and geneticist at the University of Cambridge in England told Live Science that she was inspired to explore Labrador obesity because she was seeing an unusually high number of overweight Labs in her veterinary clinic.

"When I speak to their owners, everybody says, 'My dog is really obsessed with food,'" Raffan said. "And whenever we see something that is more common in one breed of dog than another, genetics are implicated as a possible factor."

So Raffan set out to learn more about Labrador biology and to see if there was a genetic explanation.

DNA evidence

For the study, Raffan and her colleagues first looked at 33 Labradors 18 that were fit and 15 that were obese focusing on genes known to be associated with obesity. They found that the obese dogs were more likely to carry a variation of a gene called POMC that was "scrambled" in one spot, according to Raffan.

Get the worlds most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The gene variant essentially omitted an "off" switch from hunger cues. "So, that 'off' switch doesn't work properly anymore, and the dogs are much more motivated by food," she said.

After studying more than 700 additional Labs, they found the POMC gene variation in about 23 percent of the dogs approximately 1 in 4 Labradors is likely to carry this variant, the scientists noted. Not all of the Labradors with the "scrambled" gene were obese, but Raffan and her colleagues found that those dogs with the gene were more likely to beg and scavenge for food, according to surveys provided by their owners.

An evaluation of 38 other dog breeds revealed this gene variation in only one other breed flat coat retrievers, which are closely related to Labradors.

"This is a common genetic variant in Labradors and has a significant effect on those dogs that carry it, so it is likely that this helps explain why Labradors are more prone to being overweight in comparison to other breeds," Raffan said in a statement.

"No magic wand"

Unfortunately, there is no "quick fix" for overweight Labradors, Raffan said. If your dog is overweight no matter what the breed regulating food and increasing exercise are your best bets for a healthier pet.

But Labrador owners should be aware that their dogs are hard-wired to pester them more about food, and are more likely to beg, Raffan added. That doesn't mean Labrador owners should just give up on trying to control their dogs' food intake but there will be somewhat more effort involved, in order to resist the more frequent begging.

"If they're overweight, it's not that you can't fight the biology but it's more difficult," Raffan said. "Just recognize that it's much harder work for you than for someone who has a dog that isn't bothered about food."

The findings were published online today (May 3) in the journal Cell Metabolism.

Follow Mindy Weisberger on Twitterand Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook& Google+. Original article on Live Science.