What percent of Japan is obese

Overweight and obesity trends among Japanese adults: a 10-year follow-up of the JPHC Study

Appendix

Members of the Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study (JPHC Study, principal investigator: S Tsugane) Group are: S Tsugane, M Inoue, T Sobue and T Hanaoka, National Cancer Center, Tokyo, Japan; J Ogata, S Baba, T Mannami, A Okayama and Y Kokubo, National Cardiovascular Center, Osaka, Japan; K Miyakawa, F Saito, A Koizumi, Y Sano, I Hashimoto, T Ikuta and Y Tanaba, Iwate Prefectural Ninohe Public Health Center, Iwate, Japan; Y Miyajima, N Suzuki, S Nagasawa, Y Furusugi and N Nagai, Akita Prefectural Yokote Public Health Center, Akita, Japan; H Sanada, Y Hatayama, F Kobayashi, H Uchino, Y Shirai, T Kondo, R Sasaki, Y Watanabe, Y Miyagawa and Y Kobayashi, Nagano Prefectural Saku Public Health Center, Nagano, Japan; Y Kishimoto, E Takara, T Fukuyama, M Kinjo, M Irei and H Sakiyama, Okinawa Prefectural Chubu Public Health Center, Okinawa, Japan; K Imoto, H Yazawa, T Seo, A Seiko, F Ito, F Shoji and R Saito, Katsushika Public Health Center, Tokyo, Japan; A Murata, K Minato, K Motegi and T Fujieda, Ibaraki Prefectural Mito Public Health Center, Ibaraki, Japan; K Matsui, T Abe, M Katagiri and M Suzuki, Niigata Prefectural Kashiwazaki and Nagaoka Public Health Center, Niigata, Japan; M Doi, A Terao, Y Ishikawa and T Tagami, Kochi Prefectural Chuo-higashi Public Health Center, Kochi, Japan; H Sueta, H Doi, M Urata, N Okamoto and F Ide, Nagasaki Prefectural Kamigoto Public Health Center, Nagasaki, Japan; H Sakiyama, N Onga, H Takaesu and M Uehara, Okinawa Prefectural Miyako Public Health Center, Okinawa, Japan; F Horii, I Asano, H Yamaguchi, K Aoki, S Maruyama, M Ichii and M Takano, Osaka Prefectural Suita Public Health Center, Osaka, Japan; Y Tsubono, Tohoku University, Miyagi, Japan; K Suzuki, Research Institute for Brain and Blood Vessels Akita, Akita, Japan; Y Honda, K Yamagishi, S Sakurai and N Tsuchiya, Tsukuba University, Ibaraki, Japan; M Kabuto, National Institute for Environmental Studies, Ibaraki, Japan; M Yamaguchi, Y Matsumura, S Sasaki and S Watanabe, National Institute of Health and Nutrition, Tokyo, Japan; M Akabane, Tokyo University of Agriculture, Tokyo, Japan; T Kadowaki, Tokyo University, Tokyo, Japan; M Noda and T Mizoue, International Medical Center of Japan, Tokyo, Japan; Y Kawaguchi, Tokyo Medical and Dental University, Tokyo, Japan; Y Takashima and M Yoshida, Kyorin University, Tokyo, Japan; K Nakamura, Niigata University, Niigata, Japan; S Matsushima and S Natsukawa, Saku General Hospital, Nagano, Japan; H Shimizu, Sakihae Institute, Gifu, Japan; H Sugimura, Hamamatsu University, Shizuoka, Japan; S Tominaga, Aichi Cancer Center Research Institute, Aichi, Japan; H Iso, Osaka University, Osaka, Japan; M Iida, W Ajiki and A Ioka, Osaka Medical Center for Cancer and Cardiovascular Disease, Osaka, Japan; S Sato, Chiba Prefectural Institute of Public Health, Chiba, Japan; E Maruyama, Kobe University, Hyogo, Japan; M Konishi, K Okada and I Saito, Ehime University, Ehime, Japan; N Yasuda, Kochi University, Kochi, Japan; and S Kono, Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan.

Three percent weight reduction is the minimum requirement to improve health hazards in obese and overweight people in Japan

Objective: Adequate goal-setting is important in health counselling and treatment for obesity and overweight. We tried to determine the minimum weight reduction required for improvement of obesity-related risk factors and conditions in obese and overweight Japanese people, using a nationwide intervention programme database.

Methods: Japanese men and women (n=3480; mean agestandard deviation [SD], 48.35.9 years; mean body mass indexSD, 27.72.5kgm(-2)) with "Obesity Disease" or "Metabolic Syndrome" participated in a 6-month lifestyle modification programme (specific health guidance) and underwent follow-up for 6 months thereafter. The relationship between percent weight reduction and changes in 11 parameters of obesity-related diseases were examined.

Results: Significant weight reduction was observed 6 months after the beginning of the programme, and it was maintained for 1 year. Concomitant improvements in parameters for obesity-related diseases were also observed. One-third of the subjects reduced their body weight by 3%. In the group exhibiting 1% to <3% weight reduction, plasma triglycerides (TG), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and -glutamyl transpeptidase (-GTP) decreased significantly, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) increased significantly compared to the control group (1% weight change group). In addition to the improvements of these 7 parameters (out of 11), significant reductions in systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and uric acid (UA) (total 11 of 11 parameters) were observed in the group with 3% to <5% weight reduction. In the group with 5% weight reduction, the same 11 parameters also improved as those in the group with 3% to <5% weight reduction.

Conclusion: The 6-month lifestyle modification programme induced significant weight reduction and significant improvement of parameters of obesity-related diseases. All the measured obesity-related parameters were significantly improved in groups with 3% to <5% and 5% weight reduction. Based on these findings, the minimum weight reduction required for improvement of obesity-related risk factors or conditions is 3% in obese and overweight (by WHO classification) Japanese people.

Expanding options for tackling obesity in Japan

Just 4.5% of adults in Japan are classified as obese according to the World Health Organizations standard measure, but experts say that this doesnt seem to match the prevalence of obesity-related health problems. Credit: Makiko Tanigawa/Getty

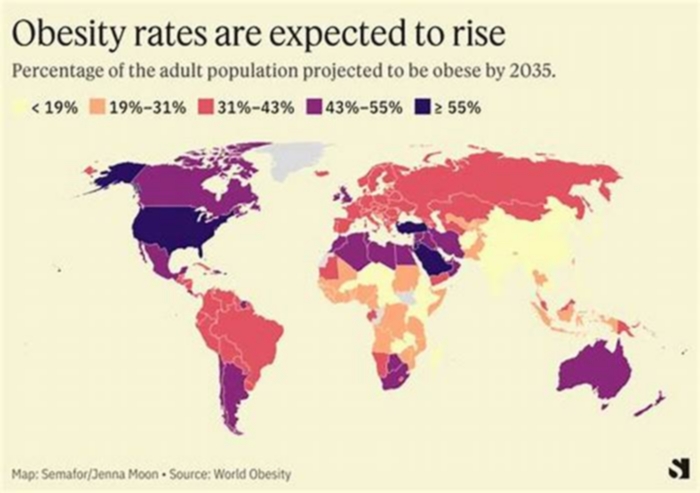

It is estimated that by 2030, about one in six people globally will be obese a condition characterized by an unhealthy excess of body fat associated with elevated risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, musculoskeletal disorders and certain types of cancer. Obesity is often associated with an accumulation of visceral fat around internal organs, and in the past has been viewed in simplistic terms as a weight management issue.

However, obesity is now recognized as a complex, chronic disease influenced by genetics, physiology, environment, education and brain function, and has become the subject of increasingly intensive research into effective prevention and treatment strategies.

The growing understanding of this disease, and in particular the molecular mechanisms underlying appetite and energy utilization, has led to a proliferation of pharmacological treatment options that can aid weight loss by targeting central nervous system pathways that regulate sensations of satiety and fullness, as well as digestion and metabolism1.

The advent of such anti-obesity drugs and their increasing availability has catalysed a change in how the disease is managed and treated.

In conjunction with lifestyle changes, including diet and exercise, anti-obesity medications can lead to significant weight loss and reduction of visceral fat, says Soichi Sakai, General Manager of the Clinical Research Division of Taisho Pharmaceutical Co., based in Tokyo, Japan.

He argues that improving health literacy around anti-obesity drugs, as part of a holistic solution, also including lifestyle changes, could help with the management of obesity and obesity-related diseases.

Important differences

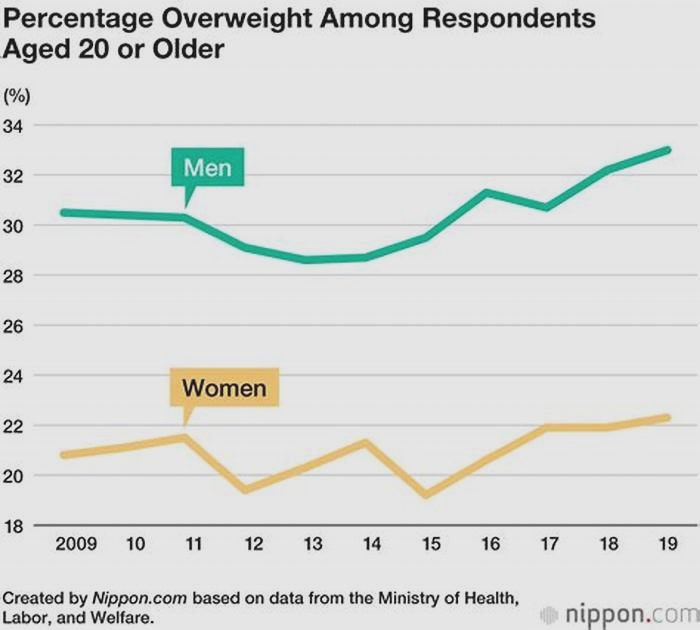

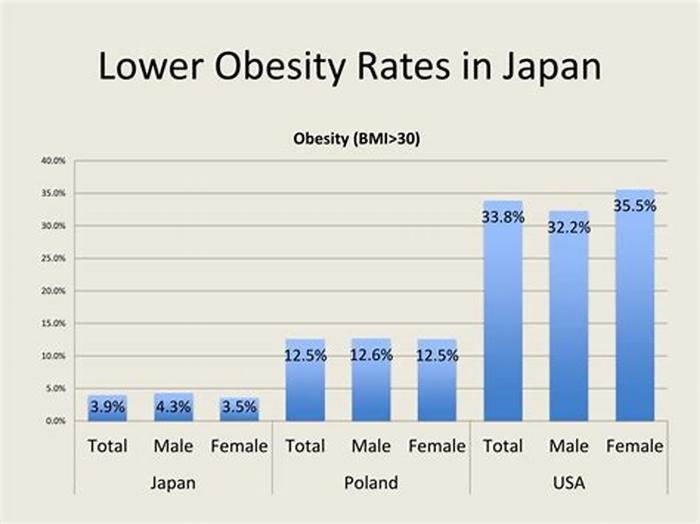

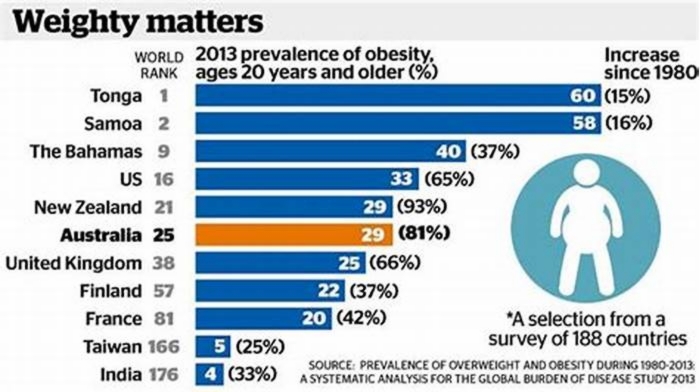

In Japan, while the incidence of weight-related type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease is on the rise, the proportion of the population classified as being clinically obese remains 10 times lower than in the US.

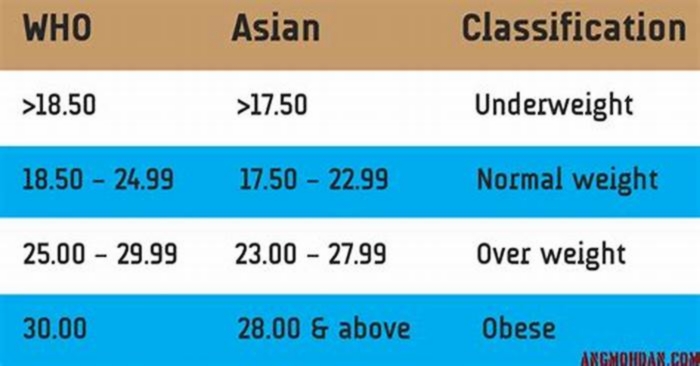

Sakai suggests that one of the reasons for this is that the Body Mass Index (BMI) widely used to screen for obesity doesnt account for differences in visceral fat distribution between populations that have Asian or European heritage2.

The pathological features of obesity in Japan differ from those in the West and other parts of the world, Sakai says. Asian populations have a higher risk of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes at a much lower BMI than Europeans.

BMI is calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the height in metres squared. According to the World Health Organization, an adult with a BMI over 30 is classified as obese. Using this criterion, only 4.5% of adults in Japan are classified as obese, which does not match the prevalence of obesity-related health problems, Sakai says.

The Japan Society for the Study of Obesity recommends instead using a BMI of 25 as the threshold for obesity for the Japanese population. It also recommends using waist measurements, 85 centimetres or more in men and 90 centimetres or more in women, as an indicator of excessive visceral fat accumulation and associated increased risk of obesity-related disorders.

Researchers argue that, by using these criteria, those at risk of obesity will be identified sooner, giving an opportunity for early intervention with treatment and prevention strategies.

Anti-obesity drugs work best when combined with lifestyle changes such as reducing fast food intake and increasing regular exercise. Credit: Oscar Wong/Getty

More treatment options

Japans clinical guidelines stipulate that obesity disease, defined as a clinical need for weight loss, can be treated pharmacologically and surgically. However, until this year, the only drug approved and available in Japan for the treatment of obesity disease was the appetite suppressor mazindol, which is a stimulant that can only be taken for short periods.

Mazindol has been used to a limited extent for patients with a BMI exceeding 35 as a short-term complement to diet and exercise in the treatment of obesity disease, says Sakai. The approval of semaglutide in March 2023 offers an alternative that can be prescribed for longer periods of time and for a wider target population.

Semaglutide is a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist that mimics the GLP-1 hormone a biomolecule released in the gut in response to eating that prompts the production of insulin. In higher doses, it also triggers the brain to suppress appetite.

Prescription drugs such as semaglutide are now widely used in other countries to treat patients with diagnosed obesity disease, and has the same potential in Japan. But preventing the development of obesity in the first place through early intervention using a combination of strategies is equally important.

In February 2023, a different drug, orlistat, was approved in Japan as the first over-the-counter medicine for the reduction of visceral fat in the treatment of obesity. Orlistat is a lipase inhibitor that reduces the absorption of dietary fat, and in combination with lifestyle changes can be used to treat excessive accumulation of visceral fat before obesity disease develops.

Prior to this, the only over-the-counter option in Japan for obesity was traditional Chinese herbal medicine, says Toru Fujita, Manager of the Clinical Research Division of Taisho Pharmaceutical Co. This situation emphasizes the need for new clinically supported3,4 drugs.

Holistic approach to weight loss

Sakai says that, as the number of drugs for long-term weight management expands, it is important to address some of the misconceptions surrounding these medications.

Many people think that they can lose weight just by taking the medication alone, Sakai says, butanti-obesity drugs work best when combined with a balanced diet, regular exercise, and lifestyle changes; they should be part of a holistic approach.

With improved health literacy and access to effective anti-obesity drugs in combination with appropriate lifestyle changes, Fujita points out we now have very effective approaches to prevent, manage and treat obesity and weight-related health problems, which will ultimately translate into reduced national healthcare costs.

Japans ageing population is leading to a rapid escalation in public spending on health, says Fujita. By attenuating the progression of obesity, anti-obesity drugs offer a solution for reducing obesity-related health care expenses. Through assisted lifestyle changes supported by such tools as lifestyle improvement smartphone apps and by taking anti-obesity drugs when appropriate, we can foster an environment where people can enjoy healthier and longer lives.

[Epidemiological aspects of overweight and obesity in Japan--international comparisons]

Abstract

Prevalence of obesity (BMI > or = 30) in Japanese adults (aged 20 years and over) was 3.8% in males and 3.2% in females (National Health and Nutrition Survey, 2010), being quite low compared with other countries listed in the Global Database on Body Mass Index (WHO). On the other hand, prevalence of overweight (BMI > or = 25) was 30.4% in males and 21.1% in females, of which overweight in males has increased in recent 35 years almost twice from 15% to 30%. Although the prevalence of overweight and obesity in Japanese adults is rather low in international comparisons, control for the obesity-associated risks through the promotion of appropriate body weight management has been prioritized in the national health programs.

Publication types

- Comparative Study

- English Abstract

- Review

MeSH terms

- Age Distribution

- Body Mass Index*

- Humans

- Japan / epidemiology

- Obesity / diagnosis

- Obesity / epidemiology*

- Overweight / diagnosis

- Overweight / epidemiology*

- Risk Factors

- Sex Factors

Obesity

Obesity is a major risk factor for a range of diseases, including heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and various types of cancer.

It is most commonly measured using the body mass index (BMI) scale.

On this page, you will find global data and research on obesity its prevalence, drivers, health consequences, and trends over time.

See all interactive charts on Obesity

Related topics:

Food Supply

How had the availability of food changed over time? How does food supply vary across the world today?

Hunger and Undernourishment

How does undernourishment vary across the world? How has it changed over time?

Micronutrient Deficiency

Food is not only a source of energy and protein, but also micronutrients vitamins and minerals which are essential to good health. Who is most affected by the "hidden hunger" of micronutrient deficiency?

Other research and writing on obesity on Our World in Data:

What is obesity?

Obesity is commonly measured using the Body Mass Index (BMI) scale

Obesity can be measured in different ways, but the most common is the Body Mass Index (BMI) scale, which is calculated based on a persons height and weight.

BMI is defined as their weight in kilograms divided by the square of their height in meters (kg/m2).1

BMI values are used to define whether an individual is considered to be underweight, healthy, overweight, or obese.

In adults, the WHO defines these categories using the cut-off points: an individual with a BMI between 25 and 30 is considered "overweight", while a BMI greater than 30 is defined as "obese".2 However, different cut-off points are used for other groups, such as children and pregnant women.

Read more in our article:

What is obesity and how is it measured?

Obesity is a leading risk factor for poor health outcomes. How is obesity defined and measured?

Obesity is one of the leading risk factors for early death

Obesity is responsible for millions of premature deaths each year

Obesity is one of the world's largest health problems one that has shifted from being a problem in rich countries to a health challenge around the world.

The Global Burden of Disease is a major global study on the causes and risk factors for death and disease.3 The authors of the study have estimated the annual number of deaths attributed to a wide range of risk factors, as you can see below.

Obesity defined as having a high body mass index is a risk factor for several of the world's leading causes of death, including heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and various types of cancer.4

As you can see, its estimated that around 5 million people died prematurely in 2019 as a result of obesity, which makes it one of the leading causes of death worldwide.

Read more in our article:

How do researchers estimate the death toll caused by each risk factor, whether its smoking, obesity, or air pollution?

Risk factors are important to understand because they can help us identify how to save lives. How do researchers estimate their impact?

The global distribution of health impacts from obesity

What share of global deaths are the result of obesity?

Globally, its estimated that almost 10% in 2019 resulted from the consequences of obesity this was almost double the share in 1990.

This share varies significantly across the world. In the map here we see the share of deaths attributed to obesity across countries.

Across many middle-income countries such as in Eastern Europe, Central Asia, North Africa, and Latin America more than 15% of deaths were attributed to obesity in 2019.

This results from both a high prevalence of obesity, as well as poorer overall health and healthcare systems compared to high-income countries with similarly high levels of obesity.

In 2019, in most high-income countries, the share of deaths attributed to obesity was in the range of 8 to 10%. In many middle-income countries, this share was almost twice as high.

In contrast, across several low-income countries especially across Sub-Saharan Africa its estimated that obesity accounts for under 5% of deaths.

There is a large difference in death rates from obesity across the world

Death rates from obesity can also help us understand differences in the impact of obesity between countries and over time.

In the map here you can see differences in death rates from obesity across the world, per 100,000 people in the population.

Death rates tend to be higher in Eastern Europe, Central Asia, North Africa, and Latin America.

In contrast, they tend to be much lower in Western Europe, Australia, and East Asia.

When we look at the relationship between death rates and the prevalence of obesity we find a positive one: death rates tend to be higher in countries where more people are obese.

But what we also notice is that for a given prevalence of obesity, death rates can vary by a factor of four. While around a quarter of people in Russia and Norway are obese, death rates in Russia are much higher.

It's not only the prevalence of obesity that plays a role but also other factors such as underlying health, other confounding risk factors (such as alcohol, drugs, smoking, and other lifestyle factors), and healthcare systems.

What share of adults are obese?

Obesity varies widely worldwide and has become more common

In the chart here, we see the share of adults (aged 18 years and older) who are obese across regions. These estimates are based on survey data and statistical modeling by the World Health Organization (WHO).

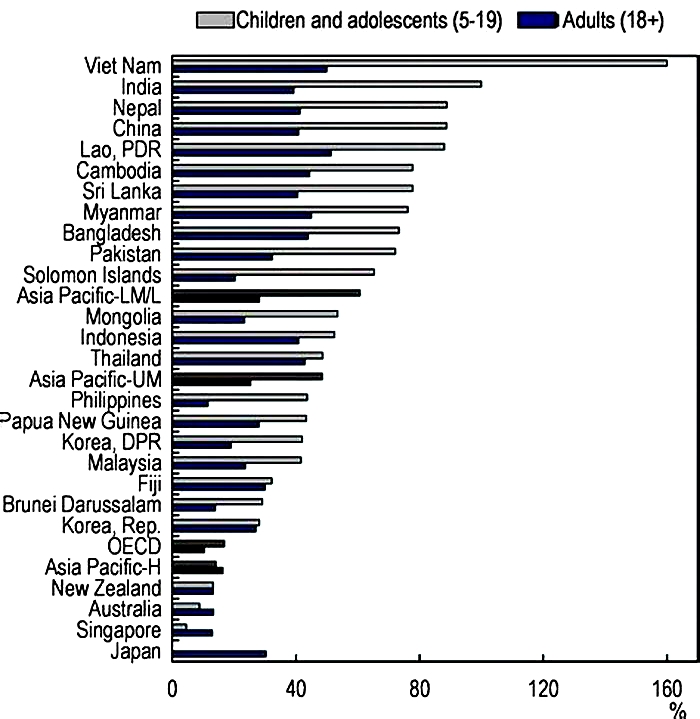

Overall we see a pattern roughly in line with prosperity: the prevalence of obesity tends to be higher in richer countries across Europe, North America, and Oceania. Obesity rates tend to be much lower across South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa.

More than a third of adults in the United States were obese in 2016. In countries such as India and Nigeria, that share was far lower.

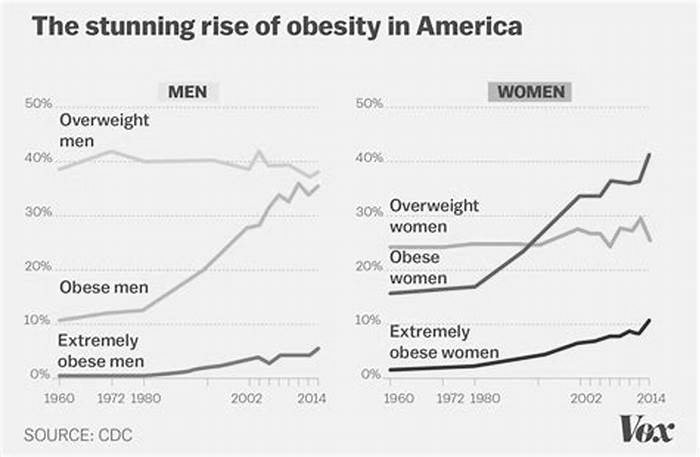

The chart also shows the share of adults who are obese has grown over time.

Obesity in men vs. women

See the data in our interactive visualization

What share of adults are overweight?

Globally, its estimated that around two-fifths of adults were overweight or obese in 2016.4

The classification of "overweight" is also defined based on the body-mass index it refers to BMI values between 25 and 30.

In the map here we see the share of adults who are overweight or obese across countries.

As you can see, the share of people who are overweight tends to be higher in richer countries and lower in poorer countries.

In many high-income countries such as the United States, its estimated that over 60% of adults are overweight or obese.

In contrast, across South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, its estimated that around one in five adults are overweight or obese.

Share of women who are overweight or obese

See the data in our interactive visualization

Body Mass Index (BMI)

Mean BMI in adult women

In the map, here we see the distribution of average (mean) BMI in adult women across the world.

In 2016, the global average (mean) BMI in women was around 25, which is the cut-off for overweight. The average BMI tends to be higher in North and South America and North Africa, and lower in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia.

Mean BMI in adult men

In the map here we see the distribution of mean BMI for adult men across the world.

In 2016, the global average (mean) BMI in men was estimated to be around 25, which is the cut-off for overweight. The average BMI tends to be higher in North and South America and North Africa, and lower in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia.

Childhood obesity

Share of children that are overweight

Obesity and overweight in children are also measured based on body mass index (BMI).

However, BMI scores are interpreted differently for children and adolescents.

Weight categories are defined by comparing weight to the WHO Growth Standards a child is defined as overweight if their weight-for-height is more than two standard deviations from the median of the WHO Child Growth Standards.4

What are the drivers of obesity?

At a basic level, weight gain eventually leading to being overweight or obesity is determined by a balance of energy.5

When we consume more energy typically measured in calories than the energy expended to maintain life and carry out daily activities, we gain weight. This is called an energy surplus. When we consume less energy than we expend, we lose weight this is an energy deficit.

This means there are two potential drivers of the increase in obesity rates in recent decades either we eat more (an increase in calorie intake) or we expend less energy in our daily life through lower activity levels. Both elements are likely to play a role in the rise in obesity.

To tackle obesity, interventions that address both energy intake and expenditureare important.6

Daily supply of calories

Over the past century but particularly over the past 50 years the supply of calories has increased across the world.

In the 1960s, the global average supply of calories (that is, the availability of calories for people to eat) was around 2,200 kcal per person per day. By 2013, this had increased to 2800kcal.

Across most countries, energy consumption has therefore increased. Without an increase in energy expenditure, weight gain and obesity tend to rise.

In the chart here, we see the relationship between the share of men who are overweight or obese versus the daily average supply of kilocalories per person.

Overall there is a strong positive relationship: countries with higher rates of overweight tend to have a higher supply of calories.

If you press "play" on the interactive timeline you can see how this has changed for each country over time. Countries tend to move upwards and to the right: the supply of calories has increased as obesity rates have increased.

Is BMI an appropriate measure of weight-related health?

The merits of using BMI as an indicator of body fat and obesity are contested.

A key contention to the use of BMI indicators is that it is a measure of body mass/weight rather than providing a direct measure of body fat.

Whilst physicians continue to use BMI as a general indicator of weight-related health risks, there are some cases where its use should be considered more carefully, which are listed below, and physicians are recommended to evaluate BMI results carefully on an individual basis.7

- Muscle mass can increase body weight; this means athletes or individuals with a high muscle mass percentage can be deemed overweight on the BMI scale, even if they have a low or healthy body fat percentage;

- Muscle and bone density tends to decline as we get older; this means that an older individual may have a higher percentage body fat than a younger individual with the same BMI;

- Women tend to have a higher body fat percentage than men for a given BMI.

Read more in our article:

What is obesity and how is it measured?

Obesity is a leading risk factor for poor health outcomes. How is obesity defined and measured?

Interactive charts on Obesity

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this topic page, please also cite the underlying data sources. This topic page can be cited as:

Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser (2017) - Obesity Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/obesity' [Online Resource]BibTeX citation

@article{owid-obesity, author = {Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser}, title = {Obesity}, journal = {Our World in Data}, year = {2017}, note = {https://ourworldindata.org/obesity}}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.