What is the obesity rate in Korea

South Korea

Obesity in Children and Adolescents: 2022 Update of Clinical Practice Guidelines for Obesity by the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity

This article summarizes the clinical practice guidelines for obesity in children and adolescents that are included in the 8th edition of the Clinical Practice Guidelines for Obesity of the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity.

| Categories: | Evidence of Management/treatment guidelines |

| Year(s): | 2022 (ongoing) |

| Target age group: | Children |

| Organisation: | Korean Society for the Study of Obesity |

| Findoutmore: | pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov |

| References: | Kang E, Hong YH, Kim J, Chung S, Kim KK, Haam JH, Kim BT, Kim EM, Park JH, Rhee SY, Kang JH, Rhie YJ. Obesity in Children and Adolescents: 2022 Update of Clinical Practice Guidelines for Obesity by the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity. J Obes Metab Syndr. 2024 Jan 9. doi: 10.7570/jomes23060. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 38193204. |

2020 Korean Society for the Study of Obesity Guidelines for the Management of Obesity in Korea

The 2020 Korean Society for the Study of Obesity Guideline for the Management of Obesity in Korea summarizes evidence-based recommendations and treatment guidelines.

| Categories: | Evidence of Management/treatment guidelines |

| Year(s): | 2020 (ongoing) |

| Target age group: | Adults |

| Organisation: | Korean Society for the Study of Obesity |

| Findoutmore: | www.jomes.org |

| References: | Kim BY, Kang SM, Kang JH, Kang SY, Kim KK, Kim KB, Kim B, Kim SJ, Kim YH, Kim JH, Kim JH, Kim EM, Nam GE, Park JY, Son JW, Shin YA, Shin HJ, Oh TJ, Hyug L, Jeon EJ, Chung S, Hong YH, Kim CH; Committee of Clinical Practice Guidelines, Korean Society for the Study of Obesity (KSSO). 2020 Korean Society for the Study of Obesity Guidelines for the Management of Obesity in Korea. J Obes Metab Syndr. 2021 May 28. doi: 10.7570/jomes21022. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34045368. |

2018 Korean Society for the Study of Obesity Guideline for the Management of Obesity in Korea

These guidelines focus on guiding clinicians and patients to manage obesity more effectively. The recommendations and treatment algorithms can serve as a guide for the evaluation, prevention, and management of overweight and obesity.

| Categories: | Evidence of Management/treatment guidelines |

| Year(s): | 2018 (ongoing) |

| Target age group: | Adults |

| Organisation: | Korean Society for the Study of Obesity |

| Linkeddocument: | Download linked document |

| References: | Seo MH, Lee WY, Kim SS, et al. 2018 Korean Society for the Study of Obesity Guideline for the Management of Obesity in Korea [published correction appears in J Obes Metab Syndr. 2019 Jun;28(2):143].J Obes Metab Syndr. 2019;28(1):40-45. doi:10.7570/jomes.2019.28.1.40 |

Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of pediatric obesity: recommendations from the Committee on Pediatric Obesity of the Korean Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutritio

The following areas were systematically reviewed, especially on the basis of all available references published in South Korea and worldwide, and new guidelines were established in each area with the strength of recommendations based on the levels of evidence: (1) definition and diagnosis of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents; (2) principles of treatment of pediatric obesity; (3) behavioral interventions for children and adolescents with obesity, including diet, exercise, lifestyle, and mental health; (4) pharmacotherapy; and (5) bariatric surgery.

| Categories: | Evidence of Management/treatment guidelines |

| Year(s): | 2018 (ongoing) |

| Target age group: | Children |

| Organisation: | Health Promotion Administryation, Ministry of Health & Welfare |

| Linkeddocument: | Download linked document |

| References: | Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of pediatric obesity: recommendations from the Committee on Pediatric Obesity of the Korean Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition. Clin Exp Pediatr. 2019;62(1):3-21. Published online December 27, 2018. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3345/kjp.2018.07360 |

Comprehensive plan for Obesity Prevention and Control

South Korea's national obesity strategy, including physical activity guidelines

| Categories: | Evidence of National Obesity Strategy/Policy or Action planEvidence of Nutritional or Health Strategy/ Guidelines/Policy/Action planEvidence of Physical Activity Guidelines/Policy |

| Year(s): | 2018 (ongoing) |

| Target age group: | Adults and children |

| Organisation: | Joint ministries |

| Linkeddocument: | Download linked document |

NCD Country Profiles 2018 (Obesity Targets)

The profiles also provide data on the key metabolic risk factors, namely raised blood pressure, raised blood glucose and obesity and National Targets on Obesity (as of 2017)

| Categories: | Evidence of Obesity Target |

| Year(s): | 2017 (ongoing) |

| Target age group: | Adults and children |

| Organisation: | World Health Organisation |

| References: | Noncommunicable diseases country profiles 2018. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. |

White Paper, Ministry of Food and Drug Safety

| Categories: | Labelling Regulation/Guidelines |

| Year(s): | 2016 (ongoing) |

| Target age group: | Adults and children |

| Organisation: | Ministry of Food and Drug Safety |

| Linkeddocument: | Download linked document |

The Physical Activity Guide for Koreans

Korea's physical activity strategy and guidelines.

| Categories: | Evidence of Physical Activity Guidelines/Policy |

| Year(s): | 2013 (ongoing) |

| Target age group: | Adults and children |

| Organisation: | Ministry of Health and Welfare |

The Special Act on the Safety Management of Childrens Dietary Life

The Special Act on the Safety Management of Childrens Dietary Life covers a series of policies to prevent obesity and improve children's diet. Article 10 stipulates that TV advertising to children under 18 years of age is prohibited for specific categories of food before, during and after programmes shown between 5pm7pm and during other childrens programmes. The restriction also applies to advertising on TV, radio and the internet that includes gratuitous incentives to purchase (eg free toys).The Act also sets nutrition standards for food sold on school premises and prevents the sale of sugar drinks and other energy-dense and nutrient-poor foods entirely.

| Categories: | Evidence of School Food RegulationsEvidence of Marketing Guidelines/Policy |

| Year(s): | 2009 (ongoing) |

| Target age group: | Children |

| Organisation: | Government |

| Findoutmore: | elaw.klri.re.kr |

General dietary guidelines for Koreans

In 1991, the National dietary guidelines were first published by the Ministry of Health and Welfare. In 2002-2003, general and age-based guidelines were announced and revised in 2008-2009. In 2016, the General Dietary Guidelines for Koreans were established as common guidelines of inter-government ministries.

Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of pediatric obesity

Provides an evidence-based systematic approach to childhood obesity in South Korea. Emphasises a family-based, comprehensive, multidisciplinary behavioural intervention which focuses on modifying lifestyle (calorie-controlled balanced diet, active vigorous physical activity and exercise, and reduction of sedentary habits, and support by the entire family, school, and community). Also emphasises the importance of starting early in life.

| Categories: | Evidence of Management/treatment guidelines |

| Target age group: | Adults and children |

| Organisation: | Pediatric Obesity Committee of the KSPGHAN Guideline Task Force (TF) |

| Findoutmore: | www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov |

| Linkeddocument: | Download linked document |

| References: | Yong et al. 2019 Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of pediatric obesity: recommendations from the Committee on Pediatric Obesity of the Korean Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition. Korean J Pediatr 2019;62(1). pp. 3-21. |

Code of Advertising Ethics

The Code states that advertising for children and youth should not express anything that might spoil them physically or morally. It also states that Criteria for concrete activities shall conform to the ICC Advertising Activities Standards"

| Categories (partial): | Evidence of Marketing Guidelines/Policy |

| Target age group: | Children |

| Organisation: | Korea Federation of Advertising Associations |

| References: | Currently a web link to this code is unavailable. If you are aware of the location of this document/intervention, please contact us at [email protected] |

GNPR 2016-17 (q7) Breastfeeeding promotion and/or counselling

WHO Global Nutrition Policy Review 2016-2017 reported the evidence of breastfeeding promotion and/or counselling (q7)

| Categories: | Evidence of Breastfeeding promotion or related activity |

| Target age group: | Adults |

| Organisation: | Ministry of Health (information provided by the GINA progam) |

| Findoutmore: | extranet.who.int |

| References: | Information provided with kind permission of WHO Global database on the Implementation of Nutrition Action (GINA): https://extranet.who.int/nutrition/gina/en |

Special Act on Safety Control of Children's Dietary Life

The South Korean Special Act on Safety Control of Children's Dietary Life recommends colour-coded labelling for use on the front of pre-packaged children's "favourite food" including cookies/candies/popsicles, breads, chocolates, dairy products, sausage (fish or meat based), some beverages, instant noodles and fast food (seaweed rolls, hamburgers, sandwiches). Guidance for the front-of-pack colour-coded labelling was issued by Public Notice (2011), and outlines three permitted designs using green, amber and red to identify whether products contain low, medium or high levels of total sugars, fat, saturated fat, and sodium.

The Foods Labelling Standards & The Labelling Standard for Health Functional Food

In South Korea, a nutrient list must be provided on select categories of pre-packaged food, including cookies/candies/popsicles, breads and dumplings, cocoa products, jams, oils, noodles and pasta, drinks and beverages, and food of special use. The Foods Labelling Standards were first enacted in 1996, and the Labelling Standard for Health Functional Food in 2004; both Standards have been revised several times since then. Based on the 1st Master Plan on Reducing Sugar Intake 201620 and the 2016 White Paper by the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety, further categories will be required to bear nutrient lists with a three-stage implementation between 2017 and 2022 (including cereals, ready-to-eat products and ready-to-cook products in 2017; dressings and sauces in 201819; Korean-style boiled grain-/meat-/fish-based food and processed food based on fruit or vegetable purees/pastes in 202022).

No actions could be found for the above criteria.

Obesity Fact Sheet in Korea, 2020: Prevalence of Obesity by Obesity Class from 2009 to 2018

INTRODUCTION

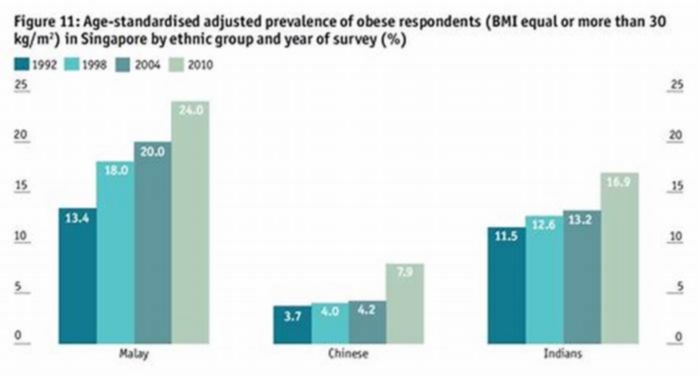

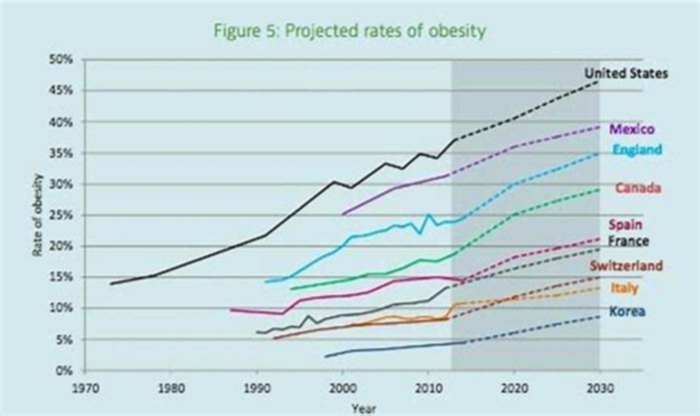

Obesity is a complex, multifactorial chronic disease that is associated with higher rates of comorbidities such as hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, obstructive sleep apnea, steatohepatitis, cardiovascular diseases, and several types of cancer, as well as higher risk of death from such comorbidities.1,2 Obesity substantially affects patient quality of life, limits economic and social activity opportunities, and imposes a considerable financial burden on patients and society. Notwithstanding the many efforts to reduce the obesity epidemic and its impact, obesity remains a major public health issue worldwide.1,2 According to the 2019 Obesity Fact Sheet by the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity (KSSO), the prevalence of obesity and abdominal obesity in Korea continuously increased in the adult population and among both sexes and nearly all age groups between 2009 and 2018.3 The rapid increase in obesity prevalence is a global phenomenon and a major healthcare challenge across both developed and developing countries. Moreover, a steep increment of the prevalence of morbid obesity warrants further research and the development of a variety of management tools.4

KSSO has invested considerable effort into investigating the epidemiology of obesity and obesity-related comorbidities in order to improve obesity and obesity-related health outcomes across Korea. For that reason, the KSSO has published Obesity Fact Sheets for Korea since 2015 in collaboration with the Korean National Health Insurance Corporation (NHIC). The Obesity Fact Sheets sought to evaluate the status of obesity and obesity-related diseases and impacts of obesity, as well as to provide health statistics for the development of national health policies on obesity in Korea. The 2020 Obesity Fact Sheet described recent trends in the prevalence of obesity by obesity class in age and sex groups, and region of South Korea. Hence, in this study, we reported its rationale and methods and discussed the prevalence of obesity classes in South Korea based on the 2020 Obesity Fact Sheet.

METHODS

Data source and study population

This study was based on the national health checkup dataset offered by the Korean National Health Insurance Service (NHIS). The Korean NHIC manages the NHIS, which is a universal and mandatory health insurance system covering 97% of Koreans and provides at least biennial health screenings for all insured Koreans. The NHIS possesses a database of nearly the whole South Korean population including demographic information, health examination data, and diagnosis of diseases and medical treatment identified by the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision and prescription codes. We analyzed data on individuals aged 20 years who underwent a health examination provided by the Korean NHIS between January 1, 2009, and December 31, 2018. The Institutional Review Board of the Kangbuk Samsung Hospital approved this study protocol (No. KBSMC 2020-05-002).

Definition of obesity and obesity classes

Trained staff measured participant height and body weight for anthropometric assessment. We calculated body mass index (BMI) by dividing body weight (kg) by the square of the height (m). We defined obesity as a BMI 25 kg/m2, according to the Asia-Pacific criteria of the World Health Organization guidelines. Obesity classes were defined using the 2018 KSSO Obesity Guideline for the Management of Obesity as follows, class I obesity, BMI 25.029.9 kg/m2; class II obesity, 30.034.9 kg/m2; class III obesity, 35.0 kg/m2.5

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). We presented the prevalence of obesity and obesity classes in the study population as a whole, as well as prevalence by age group (young: 2039 years, middle-aged: 4064 years, and elderly: 65 years), sex, and region of South Korea.

RESULTS

Prevalence of obesity by obesity class (20092018)

The prevalence of overall obesity in 2009 was 32.6% and increased by 1.18-fold to 38.5% in 2018, respectively. presents the prevalence of obesity by obesity class from 2009 to 2018 in the whole population and by sex. The prevalence of all three classes of obesity increased between 2009 and 2018 for all groups (all P for trend <0.001). In the whole sample, the prevalence of class I, II, and III obesity in 2009 was 29.1%, 3.2%, and 0.3%, respectively, and was increased by 1.12-, 1.63-, 2.79-fold in 2018 to 32.5%, 5.2%, and 0.81%, respectively (). During this period, the prevalence of each obesity class increased among both men and women (P for trend <0.001). The prevalence of class I, II, and III obesity in men was 33.5%, 3.4%, and 0.26% in 2009 and 39.4%, 6.0%, and 0.86% in 2018. In women, the prevalence was 23.7%, 3.1%, and 0.35% in 2009 and 24.6%, 4.3%, and 0.75% in 2018, respectively ().

Prevalence of obesity by obesity class (20092018) in the total population (A), men (B), and women (C) (all P for trend < 0.001). Orange, pink, and green lines represent the prevalence of class I, class II, and class III obesity, respectively.

Prevalence of obesity by obesity class in age and sex groups (20092018)

shows the prevalence of each obesity class from 2009 and 2018 among different age groups. Among all age groups, the prevalence of class I, II, and III obesity increased during this period (all P for trend <0.001). Among young individuals, the prevalence of class I, II, and III obesity was 23.7%, 3.6%, and 0.44% in 2009 and 28.3%, 6.9%, and 1.61% in 2018, respectively. The prevalence of each obesity class among middle-aged individuals was 31.6%, 3.1%, and 0.24% in 2009 and 33.6%, 4.8%, and 0.59% in 2018. Among elderly individuals, the prevalence was 31.9%, 3.1%, and 0.21% in 2009 and 35.5%, 3.9%, and 0.32% in 2018.

Prevalence of obesity classes (20092018) in young (A), middle-aged (B), and elderly (C) individuals (all P for trend < 0.001). Orange, pink, and green lines represent the prevalence of class I, class II, and class III obesity, respectively.

The age-specific prevalence of obesity classes increased between 2009 and 2018 among both men and women, as shown in . In 2018, the prevalence of class I obesity for young, middle-aged, and elderly men was 37.8%, 41.4%, and 34.8%, respectively. The prevalence of class II obesity was 8.9%, 5.4%, and 2.6% and class III obesity was 1.85%, 0.53%, and 0.12% in young, middle-aged, and elderly men, respectively. Compared to 2009, 3.8-fold increases in class III obesity were observed in young and middle-aged men in 2018. In 2018, the prevalence of class I obesity among young, middle-aged, and elderly women was 12.9%, 25.2%, and 36.1%, respectively. The prevalence of class II obesity was 3.7%, 4.2%, and 5.2% and class III obesity prevalence was 1.22%, 0.67%, and 0.51% in young, middle-aged, and elderly women, respectively. There were 2.1- and 3.5-fold increases in class II and class III obesity in young females in 2018 compared to 2009.

Age-specific prevalence of obesity classes between 2009 and 2018 in men (A-C) and women (D-F).

Prevalence of obesity classes by region

The prevalence of overall obesity and all three classes of obesity increased in all regions of South Korea in 2018 compared to 2009 (). In 2018, Jeju-si had the highest prevalence of all obesity classes and the second highest prevalence of all obesity classes was observed in Gangwon-do.

Prevalence of overall (A), class I (B), II (C), and III (D) obesity between 2009 and 2018 by region of South Korea.

DISCUSSION

Based on the 2020 Obesity Fact Sheet in Korea, the prevalence of class I, II, and III obesity continued to increase from 2009 to 2018 in the population as a whole and in all subgroups. Among the three classes of obesity, the increase in the prevalence of class III obesity during this period was the greatest in the total population and in all subgroups. The increase in the prevalence of class II and III obesity was greater among men than in women, and was greater in young individuals than among middle-aged and elderly individuals. Between 2009 and 2018, the prevalence of class III obesity increased 3.8- and 3.5-fold between 2009 and 2018 in young males and females, respectively. This factsheet highlighted a steep increase in class III obesity (morbid obesity) among the population as a whole and all subgroups in South Korea. Furthermore, increases in the prevalence of all obesity classes including class II and III obesity were the most prominent in young individuals during the past decade.

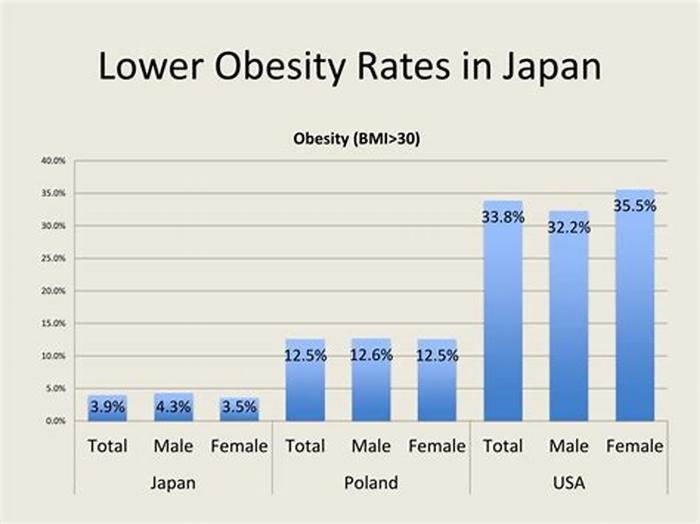

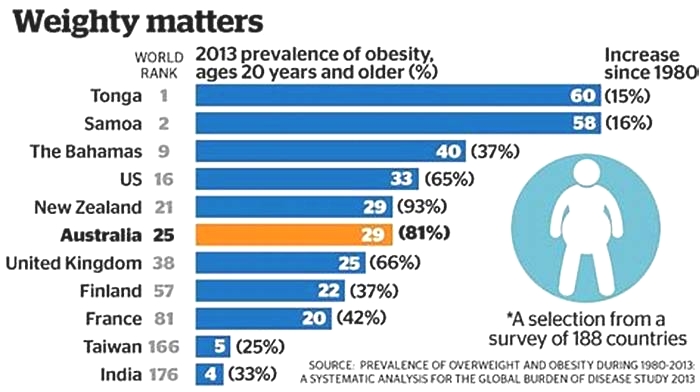

Globally, there has been a faster increase in the prevalence of higher-grade obesity or morbid obesity. A report from the National Center for Health Statistics suggested that the prevalence of overall obesity in the United States increased more than 36% from 1999 to 2014.6 In addition, an alarming prevalence increase in individual BMI categories was observed; the rate of overweight remained roughly same, while the rate of extreme obesity increased more than 6-fold to 6.6% in 2009-2010 compared to in 1962, based on National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data.6,7 In South Korea, the prevalence of class II and III obesity increased rapidly based on the 2020 Obesity Fact Sheet. Obesity is related to higher rates of comorbidities such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus, obstructive sleep apnea, certain cancers, fatty liver, gastroesophageal reflux, arthritis, and polycystic ovary syndrome.8,9 Studies revealed evidently that the risk of these diseases rises in morbid obesity. One study reported that the risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus surged at a BMI 27.2 kg/m2.10 Obesity is associated with higher rates of mortality caused by obesity-related comorbidities at higher BMI levels. A study reported that both class II and III obesity were associated with increased risk of all-cause mortality while class I obesity was not.11 Furthermore, several large cohort studies reported that weight loss by bariatric surgery reduced considerably all cause- and cause-specific mortality risk.12,13 Patients with morbid obesity are likely to take more medications due to multimorbidity associated with obesity. Severe obesity leads to impairment of activities of daily living, which results in distress to patients and aggravation of obesity.1 In this regard, it is important to classify obesity to identify the risk of comorbidities and mortality and to establish strategies to address the epidemic of morbid obesity.

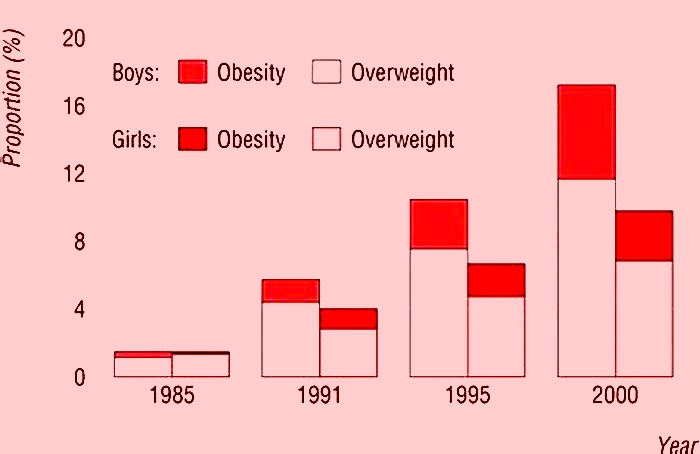

The 2020 Obesity Fact Sheet has emphasized a precipitous increasing trend in the prevalence of obesity, particularly in class III obesity, among South Korean young adults. Across the globe, all age groups have gained significant weight over the last four decades, with the most rapid weight gain occurring in young adults. Increasing rates of severe obesity in children and adolescents confer a rise in obesity prevalence and premature morbidity and mortality in young adults. Consequently, bariatric surgery has also risen in this population. Severe obesity is associated with emotional and cognitive issues as well as metabolic complications in young adults.14,15 Factors associated with obesity may also differ according to age. Young adults tend to have unhealthy dietary habits including frequent consumption of fast food, meal skipping, and eating out, as well as insufficient fruit and vegetable consumption.16 A study of two cohorts of young adult women born in 19731978 and 19891995 revealed high weight gain in all sociodemographic groups, but this was most evident in millennial women born in 19891995 with high levels of stress and depressive mood.17 Meanwhile, a great deal of research has suggested that there is a strongly positive association between obesity and the prevalence of some metabolic complications; however, some literature suggests that the relationship between obesity and metabolic risk may become weaker or stronger with age depending on the risk factor in question.18 Therefore, prevention and treatment of obesity in young adults is a global public health priority to decrease the risk of related chronic diseases and mortality in later adulthood.

Health inequalities have been noticed worldwide since the 1980s, and health disparities by sex, socioeconomic status, and region still exist. Moreover, there are still astonishing inter- and intranational differences in health, and regional disparities in the prevalence of chronic diseases including obesity continue to widen.19,20 The 2020 Obesity Fact Sheet has reported regional differences in the prevalence of obesity in Korea. There are increasing concerns regarding regional disparities in heathy diet and nutritional status among South Korean adults21 and this seems to be one of the factors affecting regional disparities in obesity prevalence in South Korea. One study reported that residents in rural areas had higher odds of an unhealthy diet such as excessive carbohydrates, low fruit, and high salted-vegetable intake compared to those in metropolitan areas.22 Differences in lifestyle patterns, health perceptions, environmental and cultural factors, and accessibility to public transportation by region may affect regional disparities in obesity prevalence. Small cities in isolated areas may have difficulty managing obesity due to relatively poor access to medical services and exercise facilities. Further investigation examining modifiable factors related to obesity in each region is needed.

This study has several limitations and strengths. We assessed the prevalence of obesity without considering any factors related to obesity in South Korea. However, this study included nearly the whole adult population of Korea who underwent national health checkups and provides invaluable data on national health statistics with regard to obesity classes. Moreover, we performed stratified analysis by age, sex, and region.

In conclusion, based on the findings of the 2020 Obesity Fact Sheet, the prevalence of class I, II, and III obesity increased between 2009 and 2018, with a dramatic increase of class II and III obesity. The prevalence of obesity overall and all classes increased most dramatically in young adults. Regional differences in obesity prevalence were also found. This studys findings provide a better understanding of the obesity epidemic in South Korea, including variation in prevalence by age and region, and suggest that appropriate strategies for obesity according to obesity class, age, and region are urgently needed.