What is the most obese country in Southeast Asia

15% Of Malaysians Obese, Still The Fattest Country In Southeast Asia

Subscribe to ourTelegramchannel for the latest stories and updates.

As the economy slowly reopens after the pandemic lockdown, more and more gyms are reopening.

In addition, weight-loss dances and exercises are also gaining popularity.

Thats because obesity is a health problem that many people are concerned with nowadays.

Although obesity is so common, it is also one of the killers that cause human death.

According to the United Nations,more than 4 million people die each year due to being overweight or obese.

Therefore, for the sake of their own health problems, preventing obesity has become the primary goal of many people.

The Malaysian Muslim Consumers Association (PPIM) further highlighted the problem with a posting on social media recently.

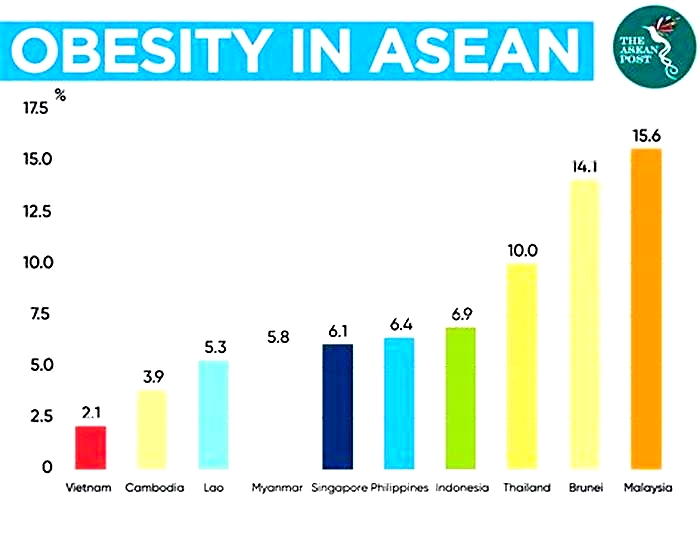

PPIM pointed out that 15.6 percent of the countrys population are obese.

Standing Out For the Wrong Reason

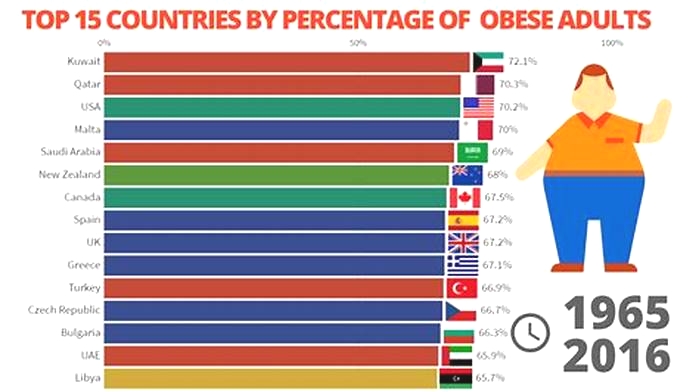

Some people may think that 15.6% is still very low, but Malaysia occupies the first place in Southeast Asia.

The second is Brunei, and the third is Thailand with 14.1% and 10% respectively.

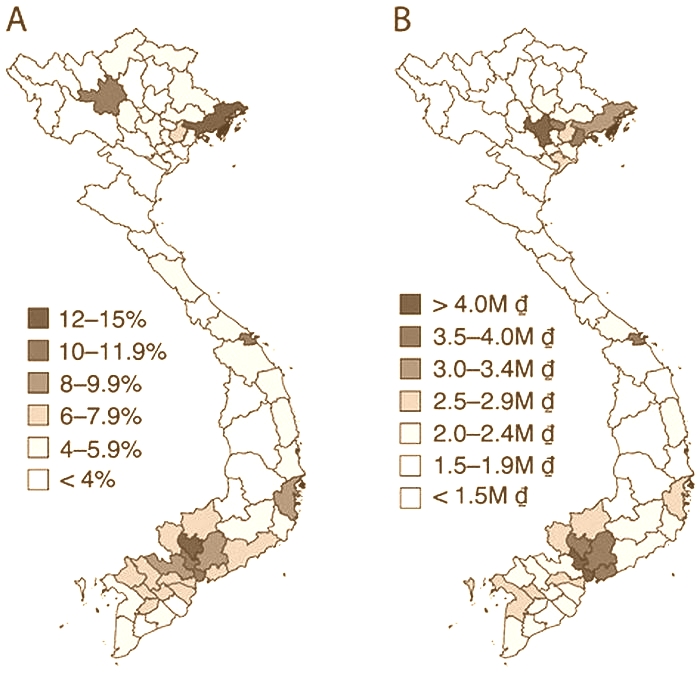

The rests are Indonesia (6.9%), the Philippines (6.4 percent), Singapore (6.1%), Myanmar (5.8%), Laos (5.3 percent), Cambodia (3.9 percent) and Vietnam (2.1 percent).

In your opinion, why many people in Malaysia are overweight?

PPIM on obesity in Malaysia

From another perspective, it means that three out of 20 people in Malaysia are facing obesity, a proportion that should ne of concern.

Blame It On The Nasi Lemak

Meanwhile, netizens also gave their two cents on the issue.

Because the people of other countries do not have nasi lemak as breakfast like the people in Malaysia.

Instagram user @mohd_alifff on obesity problems in Malaysia

Malaysians are less athletic and like to try various cuisines, the cause of weight gain.

Instagram user @deeahmad on obesity problems in Malaysia

Other netizens added that all the food in Malaysia is delicious, which is why the people are fat.

At the end of the day, let us bear in mind that obesity data is not used to scare people, but to awaken people to pay attention to health issues.

READ MORE: Why Its So Dang Hard For Malaysians To Avoid Diabetes

How Can You Prevent Being Obese

Obesity can be a killer that causes people to die, and of course it can also be prevented.

Since it can be prevented, why not prevent it?

In addition, obesity can cause diabetes, fatty liver and other problems.

And in serious cases, it affects our hearts and cerebrovascular diseases.

In addition to hypertension, it can also cause myocardial infarction, heart disease and other problems, and can also lead to our cerebral infarction or sudden death.

The most important strategies forpreventing obesityare healthyeating.

Our lifestyle, such exercises and spending time together, can also preventus frombecoming overweight.

Heres a list of some ways to avoid being overweightorhaving obesity.

- Consume less bad fat and more good fat.

- Consume less processed and sugary foods.

- Eat more servings of vegetables and fruits.

- Eat plenty of dietary fiber.

- Focus on eating lowglycemic index foods.

- Get the family involved in your journey.

- Engage in regular aerobic activity.

Share your thoughts with us on TRPsFacebook,Twitter, andInstagram.

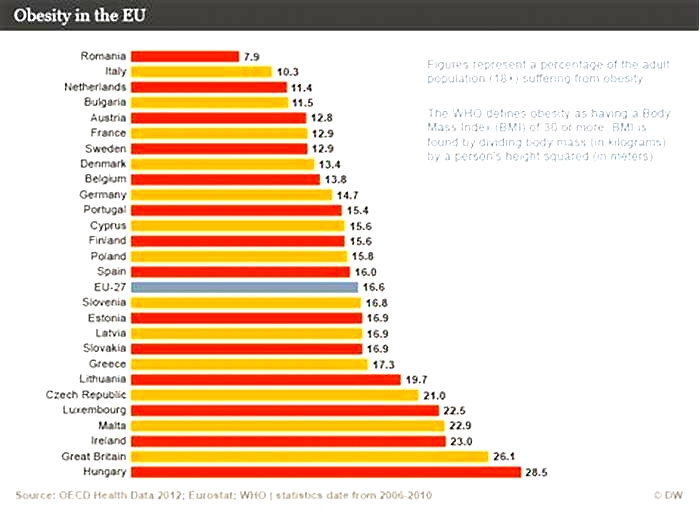

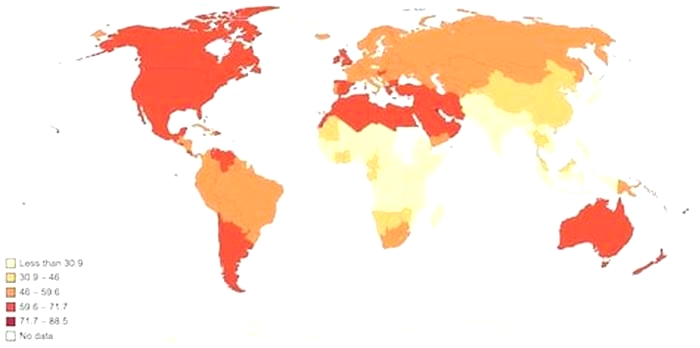

List of countries by obesity rate

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (October 2023) |

This is a list of countries ranked by the proportion of the population that is obese. The data, barring the United States, is derived from The World Factbook authored by the Central Intelligence Agency,[1] which gives the adult prevalence rate for obesity, defined as "the percent of a country's population considered to be obese". Data for U.S. obesity prevalence is derived from CDC data, recorded through the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) in March 2017 2020.[2]

Related[edit]

References[edit]

Battling the bulge

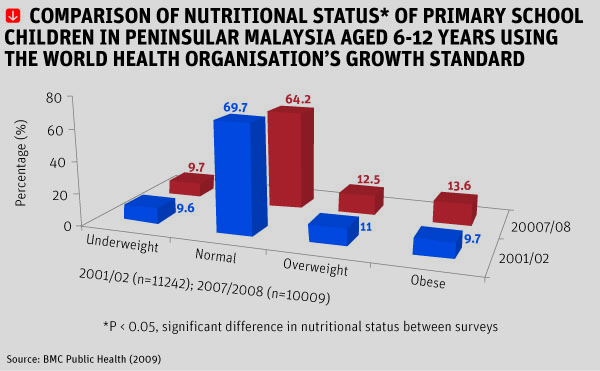

Children in Malaysia have been labelled the fattest in the region, but their weight carries a greater burden than just their size

bySacha Passi

Globesity is a growing problem often associated with the riches of the developed world but, as the term coined to describe the global spike in obesity and diet-related diseases suggests, the phenomenon is making few exceptions.

In Southeast Asia a region still grappling with the challenges of malnutrition Malaysia has earned the inglorious title of the regions fattest nation, and the sixth most obese country in Asia. Between 2006-2011 the country recorded a 14% rise in obesity among people aged 18 and above, counting 2.6 million obese adults in the country by 2011.

What is perhaps more worrying is that Malaysia has undergone a transition from under-nutrition to relative over-nutrition within a period of three decades. In April 2012, a survey by the Ministry of Health revealed that just over a quarter of Malaysian school children were obese or overweight.

Developing countries, such as Malaysia, face a double burden syndrome. While we are still grappling [with] the problem of under-nutrition, prevalence of obesity has clearly increased in the past decade, said Dr Mohd Ismail Noor, president of the Malaysian Association for the Study of Obesity (Maso). In fact, in countries like Malaysia, there are more overweight/obese children than underweight counterparts. Whats more striking, the prevalence in rural areas is as bad as those children living in urban areas.

Noor adds that irrespective of age, ethnic and social status, the prevalence of obesity is largely a result of rapid development in Malaysia. As our economy grows one of the fastest in the region food shortage is basically unheard of. The accelerated phase of industrialisation and urbanisation in recent decades has inevitably brought changes to our lifestyle.

With strong economic growth, a relatively stable government and free trade, Malaysia is on track to become a developed nation by 2020. Furthermore, the Asian Development Bank states that the countrys achievements in battling poverty and improving enrollment in primary education, gender equality, and access to healthcare services are well ahead of the 2015 target.

Lifestyle choices, genetic predisposition, learned behaviour and a lack of health awareness are all known contributors to growing numbers of obesity and overweight populations.

The fact that obese children are more likely to become obese adults, and the connection between obesity and chronic diseases such as diabetes, heart disease and cancer is not lost on the Malaysian government.

In 2011 the local government introduced an initiative for school report cards to include a students Body Mass Index (BMI) a number calculated using height and weight measurements to determine whether a person falls within a healthy weight percentile as a way for teachers and parents to monitor a childs health. Under the initiative, students with unhealthy BMIs are referred to government clinics and given counselling on healthy living. Implementation of the programme however has fallen under the discretion of individual teachers, and is loosely applied across the country.

Ive heard stories where teachers just sit at their desk and ask the children to shout-out their weight, said Noor. In short, it is a good initiative but how well it is being implemented is anyones guess.

In January 2013, Health Minister Datuk Seri Liow Tiong Lai, again stepped up the battle of obesity in schools with the introduction of a healthy lifestyle with skipping initiative to encourage children to become more active with the distribution of skipping ropes to 200 schools nationwide.

The most basic determinant of excess weight is a simple imbalance between calories consumed and calories expended. The fact that adults worldwide are struggling to grasp the concept is particularly concerning when their responsibility becomes raising healthy children.

[Malaysian] parents should pay greater attention to monitoring the meals of their children. In many families both parents are working and very often this aspect is neglected, Dr E Siong Tee, president of the Nutrition Society of Malaysia, said. Children skip breakfast meals are high in meat, fat, salt and low in vegetables and fruits. Sugary drinks including soft drinks, cordials and syrups are another popular group for children, [as are] sweet cakes and local snacks.

Many energy-dense foods are nutrient poor, taste good and are readily available in Malaysia. With more than 500 KFC outlets in the country, the international company dominates Malaysias fast food sector, marking a 41% share of industry sales in 2011. Furthermore, charitable initiatives such as KFCs Projek Penyayang, which donates meals to over 6,500 children each year in an effort to enable thousands of orphans and underprivileged children to enjoy KFC meals, seems a misguided concept considering the countrys current battle with the bulge.

On average, a healthy nine-year-old requires approximately 1,800 calories a day. Two pieces of fried chicken, mashed potato and a soft drink can total 1,300 calories or just under three-quarters of the childs total recommended daily energy intake.

A diet of fast food is high in energy and low in nutrition, proving a double-edged sword for the needs of a growing child.

A good nutritional start is vital for children to grow and develop optimally, and to be able to achieve well academically, Tee said. Prevention of obesity and other chronic diseases must start from a young age.

The implications of a prolonged lack of nutrition are serious for growing bodies, and are a known precursor for hindered brain development and intellectual capacity, as well as posing a potential risk for irreversible stunting of physical growth.

In Malaysia, widespread calcium deficiency in children is cause for concern, as is the fact that almost one in two children are low in vitamin D, based on the Recommended Nutrient Intakes (RNI) as outlined by the Malaysian Ministry of Health. Both are essential components for growth and development, but deficiency is also easily preventable.

The recommended calcium intake for a child aged from nine years is 1,300 milligrams per day, which can be achieved with the introduction of foods such as tofu, yoghurt and cheese to a childs diet.Additionally, vitamin D deficiency is easily alleviated through adequate exposure to sunlight, but Tee says an increasingly sedentary lifestyle led by Malaysian children is another challenge.

School children are just too tied down with school work, homework, tuition classes and extra curricular classes that they do not have the time and opportunity to do outdoor activities, such as games and sports, Tee said.

The physical burdens of excess weight are worrisome, but the mental impact of carrying extra weight, such as peer isolation and the development of low self-esteem in Malaysias youth, also cannot be ignored.

Fundamentally, what differentiates adult obesity and childhood obesity worldwide is that grown-ups choose the lifestyle they lead, whereas children are destined to follow the path adults tread before them.

Malaysia is no doubt reaping the benefits of rapid development, but it is also feeling the additional burden of curbing a trend that the majority of the developed world has found difficult to reverse.

Related Articles:

Fat Under Fire With the number of overweight and obese people swelling at an alarming rate, have governments left it too late to fight the flab?

Prevalence, Associated Factors and Psychological Determinants of Obesity among Adults in Selangor, Malaysia

Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Feb; 18(3): 868.

Prevalence, Associated Factors and Psychological Determinants of Obesity among Adults in Selangor, Malaysia

,1,* ,2 and 3,*

Sherina Mohd-Sidik

1Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Serdang 43400, Malaysia

Rampal Lekhraj

2Department of Community Health, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Serdang 43400, Malaysia; moc.liamtoh@1lapmar_rd

Chai Nien Foo

3Department of Population Medicine, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman, Kajang 43000, Malaysia

1Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Serdang 43400, Malaysia

2Department of Community Health, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Serdang 43400, Malaysia;

moc.liamtoh@1lapmar_rd3Department of Population Medicine, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman, Kajang 43000, Malaysia

Received 2020 Dec 9; Accepted 2021 Jan 12.

Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Abstract

Background: The pervasiveness of obesity is a growing concern in the world. This study aims to determine the prevalence of obesity among a segment of the Malaysian population, as well as investigate associated factors and psychological determinants of obesity. Methods: A cross-sectional study design was carried out in Selangor, Malaysia. A total of 1380 Malaysian adults (18 years old) participated in a structured and validated questionnaire survey. TANITA body scale and SECA 206 body meter were used to measure the respondents weight and height, from which measurements of their body mass index (BMI) were calculated. Results: The overall prevalence of obesity (BMI 30 kg/m2) among adults in Selangor, Malaysia, was 18.6%. Factors significantly associated with increased risk of obesity were: being female (OR = 1.61, 95% CI [1.202.17]), aged between 30 to 39 years old (OR = 1.40, 95% CI [1.041.88]), being Indian (OR = 1.55, 95% CI [1.132.12]), married (OR = 1.37, 95% CI [1.031.83]), and having only primary school education (OR = 1.80, 95% CI [1.172.78] or secondary school education (OR = 1.37, 95% CI [1.041.81]). In the multiple linear regression analysis (stepwise method), perceived stress (B = 0.107, p = 0.041), suicidal ideation (B = 2.423, p = 0.003), and quality of life in the physical health domain (B = 0.350, p = 0.003) inversely and significantly contributed to BMI among males. Among females, stressful life events contributed positively to BMI (B = 0.711, p < 0.001, whereas quality of life in the psychological domain had a negative effect (B = 0.478, p < 0.001) in this respect. Conclusion: There is an urgent need to integrate psychological approaches to enhance the effectiveness of obesity prevention strategies and weight-loss programs.

Keywords: obesity, risk factors, psychological, adults, Malaysia

1. Introduction

Obesity is a major global concern as it increases nations clinical burden [1,2,3]. Compared to other Asian countries, the prevalence of obesity in Malaysia topped the list partly due to Malaysians eating behaviour [4,5]. Although obesity does not directly impact morbidity and mortality, it increases the risk of various chronic diseases such as diabetes, osteoarthritis, cancers, and major vascular diseases [6,7,8,9]. Mortality from these chronic diseases is highly associated with obesity [10]. Besides, obesity also increases loading at the weight-bearing joint, leading to functional locomotor disability, the main cause of physical inactivity that contributes eventually to increased morbidity and mortality [11,12,13]. In other words, obesity indirectly shortens life expectancy while directly impacting the individuals quality of life and psychological well-being as it could lead to depression or low self-esteem [14,15,16,17].

Body mass index (BMI) can be a screening tool for weight category and moderately correlated with more direct body fat measures [18]. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines overweight and obese persons as those having BMI greater than or equal to 25 and 30 kg/m2, respectively. According to the Global Burden of Disease Study (2013), an estimated 2.1 billion people had a BMI of 25 kg/m2 or greater. The study showed that 14.1% of adults were obese (11.4% of men and 16.7% of women) [6]. The combined percentage of overweight and obesity prevalence increased by 28% in adults between 1980 and 2013 [6]. According to the WHO global status report on non-communicable diseases (2014), an estimated 39% of adults were overweight (38% of men and 40% of women), while 13% of adults were obese (11% of men and 15% of women) [19]. The prevalence of being overweight and obese is expected to rise by 2025. However, the prevalence of obesity among the adult population between 2014 and 2016 remained the same at 39% [20].

In many developing countries, including Malaysia, the prevalence of obesity, especially among urban dwellers has reached epidemic levels [21]. Among Southeast Asian countries, Malaysia recorded the highest obesity rate in adults [6,22]. Between 1996 [23] and 2015 [24], the prevalence of obesity among adults in Malaysia showed a four-fold increase, surging from 4.4% to 17.7%. In 2011 and 2015, the prevalence of being overweight among Malaysian adults was 29.4% and 30%, respectively, while during the same period, obesity accounted for 15.1% and 17.7%, respectively [25]. In the National Health and Morbidity Survey (NHMS) 2019, the current prevalence of obesity among Malaysian adults was 19.7% [26]. Pahang, Pulau Pinang, Terengganu, and Sabah showed the lowest rates of obesity (15.7%18.6%) in comparison to other states in Malaysia [26]. Between 2011 and 2019, there was an alarming rate of increase in obesity among adults in Selangor (17.1% and 19.3%) [26], a highly populated state in Malaysia [25]. As well as geographic patterning, there are ethnic disparities in the prevalence of obesity among Malaysian adults. Obesity was more prevalent in the Indian and Malay communities as compared to other ethnic groups (Chinese and others) [27,28].

Obesity is frequently linked to psychosocial issues such as low self-esteem, depression, anxiety, stress, suicidal ideation, and quality of life [29]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis study showed that obese adults had up to 32% higher risk of depression than those underweight [30]. A meta-analysis and systematic review by Gariepy, Nitka, and Schmitz revealed a moderate level of evidence for a positive association between obesity and anxiety disorders [31]. Increased BMI is significantly associated with stressful life events and perceived stress. In 2011, a meta-analysis from 14 cohort studies showed a weak positive association between stress levels (general life stress, caregiver stress, work stress) and BMI. The stress level was at its highest among subjects who were morbidly obese (BMI 40 kg/m2) [32]. A cross-sectional study conducted among 5118 Australian adults (25 years old) showed that individuals who experienced more than three stressful life events and had high levels of perceived stress, had higher BMI than those who had no stressful life events and had a low level of stress respectively [33]. Similarly, stress has been reported in other research to be associated with obesity [34].

Common obesity since some types of obesity are, in fact, a consequence of hormonal abnormalities related to syndromes and genetic disorders, reflects the uncontrollable individuals decision and engagement in behaviour that sustains weight management. Neurophysiological pathways might influence an individuals eating behaviour that undermines individuals ability to make thoughtful cognitive decisions [35]. This study investigated several factors that were thought to impact the obesity of Malaysians. The authors hypothesized that personal psychological distress (depression, anxiety, self-esteem, and suicidal ideation) and environmental factors (perceived stress, stressful life events, and quality of life) would emerge as significant contributors to obesity.

Given that obesity has been linked with significant health-related conditions and psychological effects, obesity prevention is imperative. Understanding the multiple and complex psychological determinants for obesity is crucial for developing effective prevention efforts. Despite research on the geographic and socio-demographic factors associated with obesity, there is still a paucity of studies on psychological factors leading to obesity in Malaysia. Given the incidence of obesity was amongst the highest in Selangor compared to other states in Malaysia and interactions between psychological factors leading to obesity are not yet well understood, this study aims to ascertain the prevalence, associated factors (socio-demographic variables and the presence of chronic diseases), and psychological determinants of obesity among adults in the state of Selangor, Malaysia.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sampling Frame

A cross-sectional study design was utilised with a 4-stage stratified sampling conducted by the Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOS). In the first stage, three districts (Hulu Langat, Sepang, and Klang) out of nine districts in Selangor were chosen in this study. They had almost 2.2 million people, and this proportion covered almost half of the entire population of Selangor. In the second stage, 157 Enumeration Blocks (EBs) were selected and allocated according to the particular districts proportional population size; 84 EBs were selected in Hulu Langat, 60 EBs in Klang, and 13 EBs in Sepang. In the third stage, living quarters (LQs) were selected in each EB using a systematic random sampling method. LQs in this study represented households in the community. Each EB comprised eight LQs. Finally, the respondents were randomly selected from 1256 LQs.

2.2. Sample Size

In the sample size calculation for primary outcome variable, the proportion of poor mental health status in Malaysia (11.2%) was obtained from Malaysias third NHMS [36]. The absolute error or precision was set at 2% and the response rate was set at 50%. The final estimated sample size determined by Kish L (1965) [37] was 1912 subjects that comprised the major racial groups of Malays, Chinese, and Indians.

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

The respondents in this study were Malaysian citizens, 18 years old and above, who were residents in the selected LQs.

2.4. Data Collection

Data of eligible respondents were collected during home visits by the principal researcher and a team of trained research assistants, from June to December 2012. Data on socio-demographic (gender, age, ethnicity, urban/rural residence, marital status, education level, employment status), weight, height, medical history, disability, and level of psychological status (depression, anxiety, perceived stress, self-esteem, suicidal ideation, stressful life events, and quality of life) were obtained during the home visits. The dependent variable of this study was BMI. The independent variables were gender, age, ethnicity, urban/rural residence, marital status, education level, employment status, the presence of chronic diseases (heart disease, diabetes, stroke, hypertension, arthritis, cancer, asthma, kidney failure, and thyroidism), depression, anxiety, perceived stress, self-esteem, suicidal ideation, stressful life events, and quality of life. A set of self-administrated, pre-tested, and validated questionnaires (available in English and Malay versions) was used in this study. Malay is Malaysias national language, and most Malaysian citizens can read either Malay or English or both. The measures of this study are described below.

2.4.1. Obesity

In this study, obesity was defined as having a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or greater [38]. The TANITA weighing scale (accuracy up to 0.1 kg) was used to measure body weight, while the SECA 206 Body meter (accuracy up to 0.5 mm) was used to measure height. One measurement for weight and height was taken of the participant without shoes and in light clothes by trained research assistants with the principal researchers monitoring to assure the quality of data collected. The BMI was calculated by using the formula weight (kg)/ height (m2).

2.4.2. Depression

The English and Malay versions of the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) [39] were adapted to assess depression in this study. Respondents were asked to rate the extent of depression symptoms experienced over a fortnight. The total scores ranged from 0 to 27, where higher total scores indicated more severe levels of depression. A total score of 10 and above was considered as having depression [40]. PHQ-9 is a reliable and valid instrument to measure depression, with an overall Cronbachs alpha of 0.89 [39]. The Malay versions reliability and validity score for PHQ-9 was good, with an overall Cronbachs alpha of 0.70 [40].

2.4.3. Anxiety

The English and Malay versions of the 7-items Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) questionnaire [41] were adapted to assess anxiety among respondents in this study. The respondents were asked to rate each item according to a four-point Likert scale rating from 0 to 3 (0 = not at all to 3 = nearly every day). The scores ranged from 0 to 21, whereby higher scores indicated higher levels of anxiety. Respondents with a total score of 8 or above were considered as having anxiety [42]. GAD-7 is a reliable and valid instrument to measure anxiety, with an overall Cronbachs alpha of 0.92 [41]. The Malay versions reliability and validity score for GAD-7 was good, with an overall Cronbachs alpha of 0.74 [42].

2.4.4. Perceived Stress

The English and Malay versions of the 10-item Cohens Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) questionnaire [43] were adapted to assess the respondents perceived stress in the month prior to the survey. The questionnaire was self-administrated, using a five-point Likert scale where the total scores ranged from 0 to 40. A higher score indicated higher perceived stress among the study respondents. PSS is a reliable and valid instrument to measure the perceived stress, with an overall Cronbach alpha of 0.86 [43]. The Malay version for PSS was reliable and valid, with an overall Cronbachs alpha of 0.63 [44].

2.4.5. Self-Esteem

The English and Malay versions of the 10-item Rosenbergs Self-esteem Scale (RSES) questionnaire [45] were adapted to assess self-esteem in this study. For each item, a four-point Likert scale with ratings 1 to 4 was used. The total scores ranged from 1 to 40, where higher scores indicated higher self-esteem. RSES is a reliable and valid instrument to measure self-esteem, with an overall Cronbach alpha of 0.88 [45]. The Malay versions reliability and validity score for RSES was good, with an overall Cronbachs alpha of 0.80 [46].

2.4.6. Stressful Life Events

The 17-item Kendlers Stressful Life Events questionnaire [47] was adapted to assess stressful life events experienced by the respondents in the previous year. For each item, a yes scored 1 point and no scored 0 point. A total score of 1 point indicated low stressful life events, 2 points indicated moderate stressful life events, and 3 points or above indicated high stressful life events [33].

2.4.7. Suicidal Ideation

Respondents were categorised as having suicidal ideation if they answered Yes to the ninth question in the PHQ-9 [39], which was Thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way.

2.4.8. Quality of Life

The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL-BREF-26) [48] was adapted to assess quality of life in this study. WHOQOL-BREF-26 is a 26-item self-administrated questionnaire which assesses four different domains, viz. (i) physical health, (ii) psychological health, (iii) social relationships, and (iv) environment [49]. Respondents report how much they have experienced the situation described in the questionnaire in the past two weeks on a 5-point Likert scale: 1 = not at all and 5 = completely. Each domains mean score was multiplied by 4, where a higher score indicated higher quality of life in that specific domain.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

After being screened and verified, the data in this study were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 23.0. Questionnaires with missing data were excluded from the analyses. Descriptive statistics were used to present categorical data as frequencies and percentages. Mean and standard deviation (SD) were used to describe interval and scale data in this study. Chi square test (2) was used to assess the association of socio-demographic characteristics and chronic diseases with obesity. Fishers exact test (FET) was referred when the expected frequency for a particular category was less than five. The Phi coefficient (2 2 cells) and contingency coefficient (other than 2 2 cells) were used to measure the strength of association between the dependent variables and independent variables, where <0.2 was negligible association, 0.20.4 was low association, 0.40.7 was moderate association, 0.70.9 was high association, and >0.9 was very high association (Guildford rule of thumb). Odds ratio (OR) in chi-square (2 2 cells) was used to measure the relative risk between the two groups in each social demographic characteristic (e.g., ethnic Malay and non-Malay; Chinese and non-Chinese; Indian and non-Indian). Multiple linear regression analysis (stepwise method) was used to assess the relationship between psychological factors and obesity. Variables with a p value of less than 0.25 in simple linear regression were included in the multiple linear regression model. The level of significance was set at a p value of less than 0.05 with 2-tailed test.

2.6. Ethics Statement

This study was approved by the Universiti Putra Malaysia Ethics Committee for research involving human subjects (JKEUPM), prior to the commencement of the study. The study respondents were recruited after obtaining their informed consent (written and verbal).

3. Results

Of the 1912 respondents selected, 1556 consented, thus resulting in a response rate of 81.38%. In this study, 1380 respondents were included for analysis after excluding some questionnaires for missing data (inclusion rate of 88.69%).

The majority of the study respondents were female (62.83%), aged between 20 to 29 years old (36.9%), Malays (69.1%), residing in urban areas (93.1%), married (61.7%), had attained secondary education (49.9%), and were employed at the time of data collection (51.6%). A total of 23.6% of the respondents had a history of medical problems. Approximately 1.6% of the respondents had past history of mental health problems, while 2.5% had family members with mental health problems ().

Table 1

Characteristics of the respondents in the community of Selangor (N = 1380).

| Characteristics | Overall (N = 1380) | Male (N = 513) | Female (N = 867) |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%)/Mean (SD) | |||

| Age group (years) | |||

| 19 and below | 76 (5.5) | 41 (8.0) | 35 (4.0) |

| 2029 | 509 (36.9) | 188 (36.6) | 321 (37.0) |

| 3039 | 351 (25.4) | 124 (24.2) | 227 (26.2) |

| 4049 | 221 (16.0) | 72 (14.0) | 149 (17.2) |

| 5059 | 128 (9.3) | 42 (8.2) | 86 (9.9) |

| 60 and above | 95 (6.9) | 46 (9.0) | 49 (5.7) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Malay | 954 (69.1) | 360 (70.2) | 594 (68.5) |

| Chinese | 112 (8.1) | 52 (10.1) | 60 (6.9) |

| Indian | 281 (20.4) | 87 (17.0) | 194 (22.4) |

| Others | 33 (2.4) | 14 (2.7) | 19 (2.2) |

| Residence | |||

| Urban | 1285 (93.1) | 474 (92.4) | 811 (93.5) |

| Rural | 95 (6.9) | 39 (7.6) | 56 (6.5) |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 472 (34.2) | 221 (43.1) | 251 (29.0) |

| Married | 851 (61.7) | 276 (53.8) | 575 (66.3) |

| Widowed | 49 (3.6) | 14 (2.7) | 35 (4.0) |

| Divorced | 6 (0.4) | 2 (0.4) | 4 (0.5) |

| Separated | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.2) |

| Education level | |||

| Primary | 115 (8.4) | 27 (23.5) | 88 (76.5) |

| Secondary | 681 (49.9) | 258 (37.9) | 423 (62.1) |

| Tertiary | 568 (41.6) | 224 (39.4) | 344 (60.6) |

| Employment status | |||

| Employed | 702 (51.6) | 350 (69.0) | 352 (41.2) |

| Unemployed | 599 (44.0) | 120 (23.7) | 479 (56.1) |

| Retired | 60 (4.4) | 37 (7.3) | 23 (2.7) |

| History of Medical Problems | |||

| Yes | 325 (23.6) | 118 (23.0) | 207 (23.9) |

| No | 1055 (76.4) | 395 (77.0) | 660 (76.1) |

| History of Mental Health Problems | |||

| Yes | 22 (1.6) | 11 (2.1) | 11 (1.3) |

| No | 1358 (98.4) | 502 (97.9) | 856 (98.7) |

| History of Mental Health Problems in the Family | |||

| Yes | 35 (2.5) | 10 (1.9) | 25 (2.9) |

| No | 1284 (93.0) | 478 (93.2) | 806 (93.0) |

| Not sure | 61 (4.4) | 25 (4.9) | 36 (4.2) |

| Disability | |||

| Yes | 9 (0.7) | 5 (1.0) | 4 (0.5) |

| No | 1371 (99.3) | 508 (99.0) | 863 (99.5) |

| Perceived stress (PSS) (040) SD | 15.08 (4.77) | 15.07 (4.70) | 15.09 (4.81) |

| Self-esteem (RSES) (040) SD | 19.65 (3.68) | 19.77 (3.66) | 19.58 (3.69) |

| Depression (PHQ-9) SD | 3.53 (3.58) | 3.56 (3.85) | 3.52 (3.41) |

| Present (PHQ-910) | 98 (7.1) | 46 (9.0) | 52 (6.0) |

| Absent (PHQ-9<10) | 1282 (92.9) | 467 (91.0) | 815 (94.0) |

| Anxiety (GAD-7) SD | 1.94 (2.67) | 1.80 (2.66) | 2.03 (2.68) |

| Present (GAD-7 8) | 69 (5.0) | 25 (4.9) | 44 (5.1) |

| Absent (GAD-7 < 8) | 1311 (95.0) | 488 (95.1) | 823 (94.9) |

| Suicidal Ideation | |||

| Yes | 97 (7.0) | 49 (9.6) | 48 (5.5) |

| No | 1283 (93.0) | 464 (90.4) | 819 (94.5) |

| Stressful Life Event SD | 3.56 (1.74) | 3.59 (1.84) | 3.54 (1.67) |

| No | 37 (2.7) | 9 (1.8) | 28 (3.2) |

| Low (1 stressful life event) | 152 (11.0) | 68 (13.3) | 84 (9.7) |

| Moderate (2 stressful life events) | 182 (13.2) | 78 (15.2) | 104 (12.0) |

| High (3 stressful life events) | 1009 (73.1) | 358 (69.8) | 651 (75.1) |

| Quality of Life (WHOQOL-BREF-26) SD | |||

| Physical Health (420) | 14.79 (2.16) | 14.84 (2.12) | 14.76 (2.18) |

| Psychological Health (420) | 14.56 (2.09) | 14.49 (2.20) | 14.60 (2.03) |

| Social Relationships (420) | 15.28 (2.42) | 15.38 (2.50) | 15.22 (2.38) |

| Environment (420) | 14.66 (1.97) | 14.59 (2.04) | 14.70 (1.93) |

| Weight (kg) Mean SD | 65.77 (15.42) | 70.85 (14.81) | 62.77 (15.00) |

| Height (cm) Mean SD | 161.25 (9.39) | 167.60 (8.97) | 157.49 (7.40) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) Mean SD | 25.34 (5.79) | 25.26 (5.14) | 25.38 (6.15) |

The respondents had a mean BMI of 25.34 kg/m2 (SD = 5.79), self-esteem of 19.65 (SD = 3.68), and perceived stress of 15.08 (SD = 4.77). A total of 7.1% of the respondents had depression. Anxiety and suicidal ideation are prevalent among 5% and 7% of the respondents, respectively. Overall, approximately 73.1% had experienced high stressful life events in the previous year. The overall mean score for quality of life was highest in the social relationship domain at 15.28 (SD = 2.42) compared with 14.79 (SD = 2.16) for the physical health domain, 14.56 (SD = 2.09) for the psychological health domain, and 14.66 (SD = 1.97) for the environment domain ().

shows that the prevalence of obesity among adults in Selangor was 18.6%, with a higher proportion being females (21.1%) compared to males (14.2%). In , the mean BMI measurements for males and females are almost identical (25.26 vs 25.38), yet more females are obese. shows no obvious peaks by age. Males: 19 years = 17%, 2029 = 16%, 60 = 15%; Females: 3039 = 28%, 4049 = 26%, 60 = 26%. The highest prevalence of obesity was found among the Indian respondents (24.2%; 20.7% males and 25.8% females). The proportion of obesity was higher for those residing in urban areas (18.7%), the widowed (26.5%), those who had attained only primary school education (27.8%), as well as the unemployed (20.2%), especially among females compared to males. The differences in distribution of all the study variables between males and females were not statistically significant ().

Table 2

Prevalence of obesity by socio-demographic characteristics among respondents (N = 1380).

| Characteristics | Obesity N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (N = 1380) | 256 (18.6) | ||

| Male (N = 513) | 73 (14.2) | ||

| Female (N = 867) | 183 (21.1) | ||

| Male | Female | Overall | |

| Age group (years) | |||

| 19 and below | 7 (17.1) | 3 (8.6) | 10 (13.2) |

| 2029 | 30 (16.0) | 44 (13.7) | 74 (14.5) |

| 3039 | 15 (12.1) | 64 (28.2) | 79 (22.5) |

| 4049 | 10 (13.9) | 39 (26.2) | 49 (22.2) |

| 5059 | 4 (9.5) | 20 (23.3) | 24 (18.8) |

| 60 and above | 7 (15.2) | 13 (26.5) | 20 (21.1) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Malay | 50 (13.9) | 120 (20.2) | 170 (17.8) |

| Chinese | 5 (9.6) | 11 (18.3) | 16 (14.3) |

| Indian | 18 (20.7) | 50 (25.8) | 68 (24.2) |

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 2 (10.5) | 2 (6.1) |

| Residence | |||

| Urban | 70 (14.8) | 170 (21.0) | 240 (18.7) |

| Rural | 3 (7.7) | 13 (23.2) | 16 (16.8) |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 38 (17.2) | 29 (11.6) | 67 (14.2) |

| Married | 33 (12.0) | 140 (24.3) | 173 (20.3) |

| Widow/widower | 2 (14.3) | 11 (31.4) | 13 (26.5) |

| Divorced | 0 (0.0) | 1 (25.0) | 1 (16.7) |

| Separated | 0 (0.0) | 2 (100.0) | 2 (100.0) |

| Education level | |||

| Primary | 3 (11.1) | 29 (33.3) | 32 (27.8) |

| Secondary | 33 (12.8) | 109 (25.8) | 142 (20.9) |

| Tertiary | 36 (16.1) | 42 (12.2) | 78 (13.7) |

| Employment status | |||

| Employed | 51 (14.6) | 72 (20.5) | 123 (17.5) |

| Unemployed | 17 (14.2) | 104 (21.7) | 121 (20.2) |

| Retired | 4 (10.8) | 4 (17.4) | 8 (13.3) |

In this study, the strength of association between the variables was determined based on the Phi coefficient and contingency coefficient. At the same time, the crude relative risk was obtained from Chi-square test. The findings showed a significant (2 (10.09), p = 0.001) but negligible ( = 0.086) association between obesity and gender. Females were significantly associated with obesity by 1.6 times compared to males (OR (crude) = 1.61, 95% CI [1.202.17]). Age had a significant (2 (12.84), p = 0.025) but negligible ( = 0.096) association with obesity. Two age groups were found to have a significant association with obesity. Those who were less than 30 years old had a reduced risk of obesity, especially among those aged 2029 years old (OR (crude) = 0.64, 95% CI [0.480.87]). Respondents aged 30 years old had an increased risk of being obese, especially those aged 3039 years (OR (crude) = 1.40, 95% CI [1.041.88]). The proportion of obesity was significantly higher among Indians compared to other ethnicities (24.2%; 2 (11.03), p = 0.012). Being an Indian increased the risk of obesity by 55% (OR (crude) = 1.55, 95% CI [1.132.12]) compared to other ethnicities ().

Table 3

Association between obesity and socio-demographic characteristics among respondents (N = 1380).

| Characteristics | Obese | Non-Obese | Chi-Square | Crude OR (95%CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 10.09 | 0.001 *(0.086) | |||

| Female | 183 (21.1%) | 684 (78.9%) | 1.61(1.202.17) | ||

| Male | 73 (14.2%) | 440 (85.8%) | |||

| Age (years) | 12.84 | 0.025 * (0.096) | |||

| Below 19 | 10 (13.2%) | 66 (86.8%) | 0.65 (0.331.29) | 0.213 | |

| 2029 | 74 (14.5%) | 435 (85.5%) | 0.64 (0.480.87) | 0.003 * | |

| 3039 | 79 (22.5%) | 272 (77.5%) | 1.40 (1.041.88) | 0.027 * | |

| 4049 | 49 (22.2%) | 172 (77.8%) | 1.31 (0.921.86) | 0.131 | |

| 5059 | 24 (18.8%) | 104 (81.3%) | 1.02 (0.641.62)) | 0.951 | |

| 60 and above | 20 (21.1%) | 75 (78.9%) | 1.19 (0.711.98) | 0.516 | |

| Ethnicity | 11.03 | 0.012 * (0.089) | |||

| Malay | 170 (17.8%) | 784 (82.2%) | 0.86 (0.641.14) | 0.296 | |

| Chinese | 16 (14.3%) | 96 (85.7%) | 0.71 (0.411.23) | 0.226 | |

| Indian | 68 (24.2%) | 213 (75.8%) | 1.55 (1.132.12) | 0.006 * | |

| Others | 2 (6.1%) | 31 (93.9%) | 0.28 (0.071.17) | 0.062 | |

| Residence | 0.20 | 1.13 (0.651.98) | 0.657 | ||

| Urban | 240 (18.7%) | 1045 (81.3%) | |||

| Rural | 16 (16.8%) | 79 (83.2%) | |||

| Marital status | 18.57 | 0.001 * (0.116) | |||

| Single | 67 (14.2%) | 405 (85.8%) | 0.63 (0.460.85) | 0.003 * | |

| Married | 173 (20.3%) | 678 (79.7%) | 1.37 (1.031.83) | 0.031 * | |

| Widowed | 13 (26.5%) | 36 (73.5%) | 1.62 (0.853.10) | 0.143 | |

| Divorced | 1 (16.7%) | 5 (83.3%) | 0.88 (0.107.55) | 0.691 a | |

| Separated | 2 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | - | 0.034 a,* | |

| Education level | 17.71 | <0.001 * (0.114) | |||

| Primary | 32 (27.8%) | 83 (72.2%) | 1.80 (1.172.78) | 0.007 * | |

| Secondary | 142 (20.9%) | 539 (79.1%) | 1.37 (1.041.81) | 0.024 * | |

| Tertiary | 78 (13.7%) | 490 (86.3%) | 0.57 (0.430.77) | <0.001 * | |

| Employment status | 2.66 | 0.256 | |||

| Employed | 123 (17.5%) | 579 (82.5%) | 0.87 (0.661.15) | 0.330 | |

| Unemployed | 121 (20.2%) | 478 (79.8%) | 1.22 (0.931.60) | 0.156 | |

| Retired | 8 (13.3%) | 52 (86.7%) | 0.67 (0.311.42) | 0.290 |

Marital status showed a significant but negligible association with obesity (2 (18.57), p = 0.001). Those who were single were less likely to be obese (OR (crude) = 0.63, 95% CI [0.460.85]); however, being married carried a significantly higher risk of obesity (OR (crude) = 1.37, 95% CI [1.031.83]). Individuals with primary or secondary education had a significantly higher risk of being obese (OR (crude) = 1.80, 95% CI [1.172.78] and OR (crude) = 1.37, 95% CI [1.041.81] respectively). On the other hand, those with tertiary education had a lower risk of being obese (OR (crude) = 0.57, 95% CI [0.430.77]). The results showed that rural/urban residency (2 (0.197), p = 0.657), as well as employment status (2(2.66), p = 0.256), were not associated with obesity ().

shows the association between obesity and chronic diseases. Having various chronic diseases (2 (19.00), p = 0.001; OR (crude) = 1.92, 95% CI [1.432.56]) was significantly associated with obesity, especially diabetes (2 (10.37), p = 0.001; OR (crude) = 2.01, 95% CI [1.313.10]), hypertension (2 (22.80), p = 0.001; OR (crude) = 2.37, 95% CI [1.653.41]), asthma (2 (3.99), p = 0.046; OR (crude) = 1.71, 95% CI [1.002.92]) and thyroidism (2 (5.27), p = 0.043; OR (crude) = 4.44, 95% CI [1.1017.89]).

Table 4

Association between obesity and chronic diseases among respondents (N = 1380).

| Characteristics | Obese | Non-Obese | Chi-Square | Crude OR (95%CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic disease | 19.00 | <0.001 * (0.117) | |||

| Yes | 87 (26.8%) | 238 (73.2%) | 1.92 (1.432.56) | ||

| No | 169 (16.0%) | 886 (84.0%) | |||

| Heart disease | 0.25 | 0.620 | |||

| Yes | 6 (22.2%) | 21 (77.8%) | 1.26 (0.503.16) | ||

| No | 250 (18.5%) | 1103 (81.5%) | |||

| Diabetes | 10.37 | 0.001 * (0.087) | |||

| Yes | 33 (30.0%) | 77 (70.0%) | 2.01 (1.313.10) | ||

| No | 223 (17.6%) | 1047 (82.4%) | |||

| Stroke | 0.20 | 0.546 a | |||

| Yes | 1 (12.5%) | 7 (87.5%) | 0.63 (0.085.11) | ||

| No | 255 (18.6%) | 1117 (81.4%) | |||

| Hypertension | 22.80 | <0.001 * (0.129) | |||

| Yes | 52 (32.3%) | 109 (67.7%) | 2.37 (1.653.41) | ||

| No | 204 (16.7%) | 1015 (83.3%) | |||

| Arthritis | 2.72 | 0.099 | |||

| Yes | 10 (29.4%) | 24 (70.6%) | 1.86 (0.883.95) | ||

| No | 246 (18.3%) | 1100 (81.7%) | |||

| Cancer | 0.69 | 0.408 a | |||

| Yes | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (100.0%) | - | ||

| No | 256 (18.6%) | 1121 (81.4%) | |||

| Asthma | 3.99 | 0.046 * (0.054) | |||

| Yes | 20 (27.4%) | 53 (72.6%) | 1.71 (1.002.92) | ||

| No | 236 (18.1%) | 1071 (81.9%) | |||

| Kidney Failure | 0.56 | 0.499 | |||

| Yes | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (100.0%) | |||

| No | 256 (18.6%) | 1122 (81.4%) | |||

| Thyroidism | 5.27 | 0.043 a,* (0.062) | |||

| Yes | 4 (50.0%) | 4 (50.0%) | 4.44 (1.1017.89) | ||

| No | 252 (18.4%) | 1120 (81.6%) |

In the multiple regression analysis, perceived stress (B = 0.107, p = 0.041), suicidal ideation (B = 2.423, p = 0.003), and quality of life in the physical health domain (B = 0.350, p = 0.003) were negatively associated with obesity among males (). Among females, stressful life events (B = 0.711, p < 0.001) contributed significantly to obesity, whereas quality of life in the psychological health domain (B = 0.478 p < 0.001) negatively contributed to obesity ().

Table 5

Relationship of Perceived stress (PSS), Self-esteem (RSES), Depression (PHQ-9), Anxiety (GAD-7), Suicidal Ideation, Stressful Life Event, QOLPhysical Health, QOLPsychological Health, QOLSocial Relationships and QOLEnvironment to body mass index (BMI)Male Respondents.

| Psychological Variables | Simple Linear Regression | Multiple Linear Regression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | t | p | B | t | p | |

| Perceived stress (PSS) (040) | 0.075 | 1.559 | 0.120 | 0.107 | 2.046 | 0.041 * |

| Self-esteem (RSES) (040) | 0.077 | 1.235 | 0.217 | |||

| Depression (PHQ-9) | 0.090 | 1.526 | 0.128 | |||

| Anxiety (GAD-7) | 0.050 | 0.584 | 0.559 | |||

| Suicidal Ideation | 2.062 | 2.686 | 0.007 | 2.423 | 3.031 | 0.003 * |

| Stressful Life Event | 0.088 | 0.712 | 0.477 | |||

| Quality of Life (WHOQOL-BREF-26) | ||||||

| QOLPhysical Health (420) | 0.158 | 1.470 | 0.142 | 0.350 | 2.945 | 0.003 * |

| QOLPsychological Health (420) | 0.167 | 1.621 | 0.106 | |||

| QOLSocial Relationships (420) | 0.012 | 0.135 | 0.893 | |||

| QOLEnvironment (420) | 0.050 | 0.451 | 0.652 |

Table 6

Relationship of Perceived stress (PSS), Self-esteem (RSES), Depression (PHQ-9), Anxiety (GAD-7), Suicidal Ideation, Stressful Life Event, QOLPhysical Health, QOLPsychological Health, QOLSocial Relationships and QOLEnvironment to body mass index (BMI)Female Respondents.

| Psychological Variables | Simple Linear Regression | Multiple Linear Regression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | t | p | B | t | p | |

| Perceived stress (PSS) (040) | 0.017 | 0.403 | 0.687 | |||

| Self-esteem (RSES) (040) | 0.122 | 2.167 | 0.031 | |||

| Depression (PHQ-9) | 0.055 | 0.899 | 0.369 | |||

| Anxiety (GAD-7) | 0.004 | 0.049 | 0.961 | |||

| Suicidal Ideation | 0.043 | 0.047 | 0.962 | |||

| Stressful Life Event | 0.703 | 5.730 | <0.001 | 0.711 | 5.869 | <0.001 * |

| Quality of Life (WHOQOL-BREF-26) | ||||||

| QOLPhysical Health (420) | 0.427 | 4.511 | <0.001 | |||

| QOLPsychological Health (420) | 0.469 | 4.618 | <0.001 | 0.478 | 4.789 | <0.001 * |

| QOLSocial Relationships (420) | 0.207 | 2.363 | 0.018 | |||

| QOLEnvironment (420) | 0.195 | 1.807 | 0.071 |

4. Discussion

Rapid economic growth and social changes (e.g., increasing sedentary lifestyles and the involvement of more women in the workforce) in Malaysia have led to an increase in eat-out practice [50,51], which may have contributed to the increased prevalence of obesity in Malaysia between 2011 and 2015. The results of this study also correspond to the NHMS carried out in 2015, which found that the prevalence of obesity was 18.7% among Malaysian adults in Selangor [24]. Based on our findings, the overall prevalence of obesity among adults in Selangor, Malaysia was 18.6%, consisting of 14.2% of men and 21.1% of women. This was an increased prevalence of obesity (BMI 30 kg/m2) by 3.6% compared to 15.1% in 2011 [52], and rising to 17.7% in 2015 [53]. The prevalence of obesity in China and India (around 2013) was far lower as compared to this current study (4.4% and 4.0%, respectively) [6]. Given the current urbanization trend in Malaysia, with Selangor amongst the more urbanized states, the increase in obesity might be due to changes in the daily diet (e.g., high-calorie food intake and choice of food), more sedentary lifestyle, and metabolic dysfunction [51,54], despite numerous obesity prevention programs being conducted [55,56,57].

In this study, it was found that women were more likely to be obese compared to men. This is consistent with a study in the Southeast Asian region, which found that the number of obese women was almost double that of obese men [19]. Similarly, a study conducted among women in Selangor found that the prevalence of obesity was 16.7% [58]. Although women generally ate slightly healthier food than men, most of them lacked physical activity [59]. Besides, the impact of pregnancy and childbirth could have influenced the development of obesity [54].

The findings in this study were inconsistent with that of another local study in Selangor that showed that the prevalence of obesity was higher among respondents between 40 and 59 years of age in both genders [60]. This current study indicated that the critical timeframe of weight gain in males appeared to be during the post-secondary-education period, mostly when the respondents had just left the structured school lifestyle and had a less structured and less externally-monitored environment such as the workplace or college/university [54]. Besides that, increased consumption of convenient food at the workplace or tertiary institutions while coping with busy schedules might contribute to obesity [61,62,63]. The high prevalence of obesity among women aged between 30 to 49 years old could be due to pregnancy or menopause [54,64].

Consistent with the current findings, a cross-sectional study among 16,127 Malaysians aged 15 years old found that Indians, followed by Malays, had a higher prevalence of obesity than the Sarawakian indigenous group, the Chinese, and the Sabahan indigenous group [28]. Similarly, a recent study by Wan Mohamud and colleagues found that among 4428 adults aged 18 years old and above, Indians and Malays had the highest prevalence of obesity [27]. Another recent study in 2016 also reported that the prevalence of obesity among Indians in Malaysia was highest, followed by the Malays, while the Chinese were the least obese ethnic group in the country [65]. The metabolic syndrome that disproportionately affects Indians in Malaysia is less engagement in physical activity and the consumption of fewer fruits and vegetables than Malays and Chinese [66].

In this study, obesity was also more prevalent among those who were married and had attained only primary and secondary education; these results were consistent with previous studies evaluating the associations of marital status [67,68] and educational background [69,70] with obesity. Generally, having a lower education background was associated with a lack of access to health-related information and healthy lifestyle choices, leading to higher body weight [71]. Individuals in different social positions have different coping mechanisms, and each of them will experience a different level of perceived stress, which significantly influences the probability of being obese [72].

The detrimental health consequences of obesity have been shown to contribute to three of the four most significant non-communicable diseases (diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and respiratory disease) [19,73,74]. This is in line with this studys findings, which showed increased risk associations with diabetes, hypertension, asthma, and thyroidism as BMI reached 30 kg/m2 and above. Data from systematic reviews of 97 cohorts among 1.8 million respondents showed that raised blood pressure contributed 31% to coronary heart disease risk among obese people [6]. The current findings are supported by the Malaysias NHMS in 2011 where almost 1 in 7 overweight and obese Malaysian adults had type 2 diabetes mellitus [52]. It is important to note that dietary glycemic index (GI) may play an essential role in body weight regulation.

Besides, our findings suggest that contributing psychological factors to BMI between males and females vary slightly. Based on our findings, perceived stress, suicidal ideation, and quality of life in the physical health domain had significant and negative relationships with BMI among males. In this study, suicidal ideation was present among male respondents (9.6%). It is vital to introduce routine screening for suicidal ideation, although the relationship between suicidal ideation and BMI was negative. The physical health domain (quality of life) was a significant predictor of BMI among the male respondents. Consistent with these findings, a study by Truthmann et al. from the German Health Interview and Examination Survey 2008 to 2011 found that BMI was significantly associated with lower physical health quality of life [75]. A systematic review by Warkentin et al. [76] reported that there was an interrelationship between weight loss and modest improvement in physical health quality of life. This was found especially among males as they became more aware of the importance of exercise, medical substances, work-life balance capacity, sleep, and rest to manage obesity. This was further supported by the Global Status Report on Non-communicable Diseases from WHO, which revealed that the prevalence of insufficient physical activity among Malaysians was more apparent in women (58.0%) than in men (46.7%). In addition, perceived stress was identified as a significant predictor of BMI among male respondents as their low tolerance of stress might influence their eating behaviour, either under or overeating [19]. Empirical evidence from previous studies revealed a significant linkage between chronic life stress and obesity [33,62,77,78,79]. The relationship between low tolerance of stress and increased BMI was attributed to neurobiology stress. This leads to hunger and comfort eating that causes a reduction of lipolytic growth hormones, thus leading to fat accumulation [80].

For females, quality of life in the psychological domain was also a significant predictor of BMI. Women may lack a positive outlook of their body image owing to a powerful but false concept of a slim body as the only and/or ultimate body shape. Furthermore, a thin body is perceived as being more socially valued among women in the higher socioeconomic class [81]. Obese females have degrading mental health as they are more concerned with the societal standards of beauty and obesity stigma. In this study, stressful life events were a significant predictor of BMI among female respondents. Females are more emotionally vulnerable to social stressors that trigger negative metabolic consequences. As a result, they turn to eat high dietary palatable foods, which, in turn, promote weight gain [82]. Moreover, one possible mechanism that could explain this unhealthy behavioural response is the activation of the pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis, thus increasing the cortisol and leptin levels and central adiposity [82].

This studys strength is the sampling method used to reduce bias and improve the representativeness of the study sample. Although this study was conducted in only one state (Selangor), to date no other study has examined the association between psychological determinants and obesity in the Malaysian community. Therefore, this studys outcome can be used as a reference point for future studies involving the general population of Malaysia. The findings of this study can be used to develop more focused community mental health interventions as a strategy for obesity management. The hypothesized relation between psychological determinants and obesity is compounded by diet [83]. Future intervention investigation is needed to establish the mechanisms that link diet and mental well-being to improve weight management. However, the correlation between BMI and body fatness is relatively strong [18]. It overestimates obesity in muscular individuals and underestimates in the elderly who have lost body mass. Besides, this study does not reveal the number of years the respondents had been diagnosed with chronic diseases. Thus, it is difficult to establish the true association between current obesity status and history of chronic diseases. The limitation of the temporal relationship in this study may be that the risk factors and BMI would be measured simultaneously, and one would be hard-pressed to say which came first. Therefore, future studies should include longitudinal designs to better explicate the psychological predictors of obesity in terms of determining causal relationships and direction. It is also important to evaluate the role of confounding variables such as socio-demographic background and history of chronic diseases on psychological risk, especially in different underlying biological pathways in the development of obesity.

5. Conclusions

Female adults, aged between 30 to 39 years old, being Indian, married, and having only primary school education or secondary school education were significantly associated with increased risk of obesity. Psychological determinants of obesity for males are perceived stress, suicidal ideation, and quality of life in the physical health domain. Among females, stressful life events and quality of life in the psychological domain contributed significantly to obesity. Nevertheless, this studys outcomes can be used to integrate psychological approaches to enhance the effectiveness of obesity prevention strategies such as weight-loss programs in community settings. Therefore, it would be beneficial to consider integrating obesity control programs with psychological intervention programs delivered by health professionals to tackle this epidemic that is becoming more prevalent and is placing much stress on the nations healthcare resources.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their appreciation to all the participants who participated in this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, S.M.-S., R.L. and C.N.F.; Validation, S.M.-S. and R.L.; Formal analysis, C.N.F.; Investigation and data curation, S.M.-S. and R.L.; Writing original draft, S.M.-S. and C.N.F.; Review and editing, S.M.-S., R.L. and C.N.F.; Supervision, S.M.-S. and R.L.; Project administration, S.M.-S. and R.L.; Funding acquisition, S.M.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Lembaga Promosi Kesihatan Malaysia (LPKM) under the project grant number (4) LPKM/04/061/06/06. The study was also funded by the E-science Fund Ministry of Science and Technology Malaysia (MOSTI) under the project grant number 06-01-04-SF1587.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the University Research Ethics Committee of Universiti Putra Malaysia on 14th August 2011 (Reference No: UPM/TNCPI/RMC/1.4.18.1 (JKEUPM). F1).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publishers Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

1.

Dietz W.H., Baur L.A., Hall K., Puhl R.M., Taveras E.M., Uauy R. Management of obesity: Improvement of health-care training and systems for prevention and care. Lancet. 2015;385:25212533. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61748-7. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]2.

Davis D., Phares C.R., Salas J., Scherrer J. Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity in US-Bound Refugees: 20092017. J. Immigr. Minor. Health. 2020 doi:10.1007/s10903-020-00974-y. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]3.

Bray G.A., Frhbeck G., Ryan D.H., Wilding J.P.H. Management of obesity. Lancet. 2016;387:19471956. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00271-3. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]4.

Ruiz Estrada M.A., Swee Kheng K., Ating R. The Evaluation of Obesity in Malaysia. SSRN Electron. J. 2019 doi:10.2139/ssrn.3455108. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]5.

Lim Z.M., Chie Q.T., The L.K. Influence of dopamine receptor gene on eating behaviour and obesity in Malaysia. Meta Gene. 2020:100736. doi:10.1016/j.mgene.2020.100736. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]6.

Ng M., Fleming T., Robinson M., Thomson B., Graetz N., Margono C. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 19802013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384:766781. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60460-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]7.

Longo M., Zatterale F., Naderi J., Parrillo L., Formisano P., Raciti G.A. Adipose Tissue Dysfunction as Determinant of Obesity-Associated Metabolic Complications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:2358. doi:10.3390/ijms20092358. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]8.

Akoumianakis I., Antoniades C. Impaired Vascular Redox Signaling in the Vascular Complications of Obesity and Diabetes Mellitus. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2019;30:333353. doi:10.1089/ars.2017.7421. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]9.

Foo C.N., Arumugam M., Lekhraj R., Lye M.S., Mohd-Sidik S., Osman Z.J. Effectiveness of health-led cognitive behavioral-based group therapy on pain, functional disability and psychological outcomes among knee osteoarthritis patients in Malaysia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 2020;17:6179. doi:10.3390/ijerph17176179. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]12.

Wilson L.F., Baade P.D., Green A.C., Jordan S.J., Kendall B.J., Neale R.E. The impact of changing the prevalence of overweight/obesity and physical inactivity in Australia: An estimate of the proportion of potentially avoidable cancers 20132037. Int. J. Cancer. 2019;144:20882098. doi:10.1002/ijc.31943. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]13.

Fu Q.G., Chye Wah Y., Sura S., Jagadeesan S., Chinnavan E., Judson J.P.E. Influence of rearfoot alignment on static and dynamic postural stability. Int. J. Ther. Rehabil. 2018;25:628635. doi:10.12968/ijtr.2018.25.12.628. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]14.

Greenberg J.A. Obesity and early mortality in the United States. Obesity. 2013;21:405412. doi:10.1002/oby.20023. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]16.

Milaneschi Y., Simmons W.K., Van Rossum E.F.C., Penninx B.W. Depression and obesity: Evidence of shared biological mechanisms. Mol. Psychiatry. 2019;24:1833. doi:10.1038/s41380-018-0017-5. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]17.

Sutaria S., Devakumar D., Yasuda S.S., Das S., Saxena S. Is obesity associated with depression in children? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Dis. Child. 2019;104:6474. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2017-314608. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]18.

Garrow J.S., Webster J. Quetelets index (W/H2) as a measure of fatness. Int. J. Obes. 1985;9:147153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]20.

World Health Organisation . Obesity and Overweight. World Health Organisation; Geneva, Switzerland: 2020. [Google Scholar]22.

Kasirye F., Wahid N. Factors Influencing Obesity among Malaysian Young Adults in Kuala Lumpur. Asian J. Res. Educ. Soc. Sci. 2020;2:5471. [Google Scholar]24.

Institute for Public Health . Non-Communicable Diseases, Risk Factors & Other Health Problems. Volume II Ministry of Health Malaysia; Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: 2015. National Health and Morbidity Survey 2015 (NHMS 2015) [Google Scholar]25.

Mohamad Nor N.S., Ambak R., Mohd Zaki N., Abdul Aziz N.S., Cheong S.M., Abd Razak M.A. An update on obesity research pattern among adults in Malaysia: A scoping review. BMC Womens Health. 2018;18:114. doi:10.1186/s12905-018-0590-4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]26.

Institute for Public Health . Non-Communicable Diseases: Risk Factors and other Health Problems. Volume 1. National Institutes of Health; Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: 2019. [(accessed on 30 July 2020)]. pp. 1392. Available online: http://www.iku.gov.my/nhms-2019 [Google Scholar]27.

Wan Mohamud W.N., Musa K.I., Md Khir A.S., Ismail A.A., Ismail I.S., Abdul Kadir K. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among adult Malaysians: An update Short Communication Prevalence of overweight and obesity among adult Malaysians: An update. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011;20:3541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]28.

Rampal L., Rampal S., Geok Lin K., Zain A., Shafie O., Ramlee R. A national study on the prevalence of obesity among 16, 127 Malaysians. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007;16:561566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]29.

Dixon J.B. The effect of obesity on health outcomes. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2010;316:104108. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2009.07.008. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]30.

Pereira-Miranda E., Costa P.R.F., Queiroz V.A.O., Pereira-Santos M., Santana M.L.P. Overweight and Obesity Associated with Higher Depression Prevalence in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2017;36:223233. doi:10.1080/07315724.2016.1261053. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]31.

Gariepy G., Nitka D., Schmitz N. The association between obesity and anxiety disorders in the population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Obes. 2010;34:407419. doi:10.1038/ijo.2009.252. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]32.

Wardle J., Chida Y., Gibson E.L., Whitaker K.L., Steptoe A. Stress and Adiposity: A Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Studies. Obesity. 2011;19:771778. doi:10.1038/oby.2010.241. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]33.

Harding J.L., Backholer K., Williams E.D., Peeters A., Cameron A.J., Hare M.J.L. Psychosocial stress is positively associated with body mass index gain over 5 years: Evidence from the longitudinal AusDiab study. Obesity. 2014;22:277286. doi:10.1002/oby.20423. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]34.

Tomiyama A.J. Stress and Obesity. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2019;70:703718. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102936. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]36.

Institute for Public Health . The Third National Health and Morbidity Survey NHMS III. Institute for Public Health; Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: 2006. [Google Scholar]37.

Kish L. Survey Sampling. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; New York, NY, USA: 1965. [Google Scholar]38.

World Health Organization Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004;363:902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]39.

Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B.W. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001;16:606613. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]40.

Sherina M.S., Arroll B., Goodyear-Smith F. Criterion validity of the PHQ-9 (Malay version) in a primary care clinic in Malaysia. Med. J. Malays. 2012;67:309315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]41.

Spitzer R.L., Kroenke K., Williams J.B.W., Lwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006;166:10921097. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]42.

Sidik S.M., Arroll B., Goodyear-Smith F. Validation of the GAD-7 (Malay version) among women attending a primary care clinic in Malaysia. J. Prim. Health Care. 2012;4:511. doi:10.1071/HC12005. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]44.

Sandhu S.S., Ismail N.H., Rampal K.G. The malay version of the perceived stress scale (PSS)-10 is a reliable and valid measure for stress among nurses in Malaysia. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2015;22:2631. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]46.

Mohd Jamil B. Validity and Reliability Study of Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale in Seremban School Children. J. Psychiatry. 2006;15:3539. [Google Scholar]47.

Kendler K.S., Thornton L.M., Gardner C.O. Stressful life events and previous episodes in the etiology of major depression in women: An evaluation of the kindling hypothesis. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2000;157:12431251. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.157.8.1243. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]49.

Pimenta F.B.C., Bertrand E., Mograbi D.C., Shinohara H., Landeira-Fernandez J. The relationship between obesity and quality of life in Brazilian adults. Front. Psychol. 2015;6:17. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00966. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]50.

Ali N., Abdullah M.A. The food consumption and eating behaviour of Malaysian urbanites: Issues and concerns. Malays. J. Soc. Sp. 2012;8:157165. [Google Scholar]51.

Fournier T., Tibre L., Laporte C., Mognard E., Ismail M.N., Sharif S.P. Eating patterns and prevalence of obesity. Lessons learned from the Malaysian Food Barometer. Appetite. 2016;107:362371. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2016.08.009. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]52.

Malaysia Ministry of Health . National Health and Morbidty Survey 2011Non Communicable Diseases. Volume 2 Ministry of Health; Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: 2011. [Google Scholar]53.

Ministry of Health Malaysia . National Health and Morbidity Survey 2015Non Communicable Diseases, Risk Factors & Other Health Problems. Volume 2 Ministry of Health Malaysia; Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: 2015. [Google Scholar]55.

Koo H., Poh B., Abd Talib R. The GReat-ChildTM Trial: A Quasi-Experimental Intervention on Whole Grains with Healthy Balanced Diet to Manage Childhood Obesity in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Nutrients. 2018;10:156. doi:10.3390/nu10020156. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]56.

Hatta N.K.B.M., Rahman N.A.A., Rahman N.I.A., Haque M. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices among Mothers Regarding Childhood Obesity at Kuantan, Malaysia. Int. Med. J. 2017;24:200204. [Google Scholar]57.

Peng F.L., Hamzah H.Z., Nor N.M., Said R. Burden Of Disease Attributable To Overweight And Obesity In Malaysia. Malays. J. Public Health Med. 2018;18:1118. [Google Scholar]58.

Sidik S., Rampal L. The prevalence and factors associated with obesity among adult women in Selangor, Malaysia. Asia Pac. Fam. Med. 2009;8:2. doi:10.1186/1447-056X-8-2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]59.

Gan Q.F., Foo C.N., Choy K.W., Tan B.C., Ong K.W., Chye W.Y. Lifestyle Affects the Static and Dynamic Balance Among Malaysian Youth Population, Proceedings of the Sixth Asia-Pacific Conference on Public Health Urbanisation Challenges for Health. Penang, Malaysia, 2225 July, 2019. Med. J. Malays. 2019;74(Suppl. 2):107. [Google Scholar]60.

Lekhraj Rampal G.R., Sanjay R., Azhar M.Z., Sherina M.S., Ambigga D., Rahimah A. A Population-based Study on the Prevalence and Factors Associated with Obesity in Selangor. Malays. J. Med. Health Sci. 2006;2:8997. [Google Scholar]61.

Devine C.M., Farrell T.J., Blake C.E., Wethington E., Bisogni C.A. Work Conditions and the Food Choice Coping Strategies of Employed Parents. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2009;41:365370. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2009.01.007. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]62.

Wan Mohamed Radzi C., Salarzadeh Jenatabadi H., Alanzi A., Mokhtar M., Mamat M., Abdullah N. Analysis of Obesity among Malaysian University Students: A Combination Study with the Application of Bayesian Structural Equation Modelling and Pearson Correlation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019;16:492. doi:10.3390/ijerph16030492. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]63.

Ishak Z., Suet Fin L., Abdul Hakim Wan Ibrahim W., Yahya A., Md Zain F., Selamat R. Fast Foods, Emotional and Behavioural Problems among Overweight and Obese Adolescents Participating in MyBFF@school Intervention Program. SAGE Preprints Community. 2019:111. doi:10.31124/advance.9601190.v1. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]64.

Isacco L., Miles-Chan J.L. Gender-specific considerations in physical activity, thermogenesis and fat oxidation: Implications for obesity management. Obes. Rev. 2018;19:7383. doi:10.1111/obr.12779. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]65.

Haji Zainuddin A.A. Prevalence and Socio-demographic Determinant of Overweight and Obesity among Malaysian Adult. Int. J. Public Health Res. 2016;6:661669. [Google Scholar]66.

Tan A.K.G., Dunn R.A., Yen S.T. Ethnic disparities in metabolic syndrome in Malaysia: An analysis by risk factors. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 2011;9:441451. doi:10.1089/met.2011.0031. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]68.

Klos L.A., Sobal J. Marital status and body weight, weight perception, and weight management among U.S. adults. Eat. Behav. 2013;14:500507. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.07.008. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]69.

Devaux M., Sassi F., Church J., Cecchini M., Borgonovi F. Exploring the relationship between education and obesity. OECD J. Econ. Stud. 2011:121159. doi:10.1787/eco_studies-2011-5kg5825v1k23. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]71.

Memish Z.A., El Bcheraoui C.E., Tuffaha M., Robinson M., Daoud F., Jaber S. Obesity and associated factorsKingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2013. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2014;11:140236. doi:10.5888/pcd11.140236. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]72.

Moore C.J., Cunningham S.A. Social Position, Psychological Stress, and Obesity: A Systematic Review. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2012;112:518526. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2011.12.001. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]73.

Csige I., Ujvrosy D., Szab Z., Lorincz I., Paragh G., Harangi M. The Impact of Obesity on the Cardiovascular System. J. Diabetes Res. Hindawi Ltd. 2018:112. doi:10.1155/2018/3407306. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]74.

Gutierrez J., Alloubani A., Mari M., Alzaatreh M. Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors: Hypertension, Diabetes Mellitus and Obesity among Tabuk Citizens in Saudi Arabia. Open Cardiovasc. Med. J. 2018;12:4149. doi:10.2174/1874192401812010041. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]75.

Truthmann J., Mensink G.B.M., Bosy-Westphal A., Hapke U., Scheidt-Nave C., Schienkiewitz A. Physical health-related quality of life in relation to metabolic health and obesity among men and women in Germany. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 2017;15:17. doi:10.1186/s12955-017-0688-7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]76.

Warkentin L.M., Das D., Majumdar S.R., Johnson J.A., Padwal R.S. The effect of weight loss on health-related quality of life: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Obes. Rev. 2014;15:169182. doi:10.1111/obr.12113. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]77.

Moghimi-dehkordi B., Safaee A., Vahedi M., Amin M. Association between perceived depression, anxiety and stress with Body Mass Index: Results from a community-based cross-sectional survey in Iran. Ital. J. Public Health. 2011;8:128136. [Google Scholar]79.

Weschenfelder J., Bentley J., Himmerich H. Adipose Tissue. InTech; Bolton, UK: 2018. Physical and Mental Health Consequences of Obesity in Women; pp. 123160. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]81.

Gavin A.R., Simon G.E., Ludman E.J. The association between obesity, depression, and educational attainment in women: The mediating role of body image dissatisfaction. J. Psychosom. Res. 2010;69:573581. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.05.001. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]82.

Conklin A.I., Guo S.X.R., Yao C.A., Tam A.C.T., Richardson C.G. Stressful life events, gender and obesity: A prospective, population-based study of adolescents in British Columbia. Int. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2019;6:4146. doi:10.1016/j.ijpam.2019.03.001. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]