Is obesity a problem in Malta

Overweight and obesity - BMI statistics

Obesity in the EU: gender differences

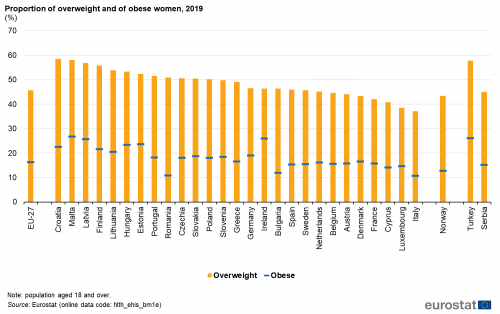

The data in this article are from the third round of the European health interview survey (EHIS) which was conducted between 2018 and 2020 and which covered persons aged 15 and over. These data indicate that substantial differences exist in the EU concerning the proportion of adults who are overweight or obese in terms of gender and socio-economic background.

Figure 1: Proportion of overweight and obese women, 2019

(%)

Source:Eurostat

(hlth_ehis_bm1e)

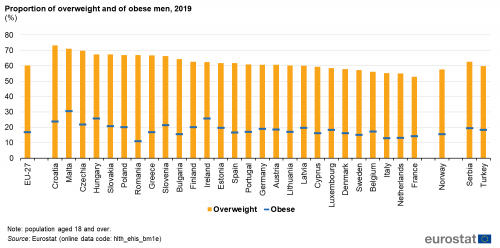

Figure 2: Proportion of overweight and obese men, 2019

(%)

Source:Eurostat

(hlth_ehis_bm1e)In the EU the proportion of adults (aged 18 years and over) who were considered to be overweight varied in 2019 between 37.1% in Italy and 58.5% in Croatia for women and between 52.9 % in France and 73.2% in Croatia for men (see Table1).

In 2019, the highest proportion of obese men and women was recorded in Malta.

In 2019, for the population aged 18years and over, the lowest proportions of women considered to be obese were observed in Italy (10.7%), Romania (10.8%), Bulgaria (11.9%) and Cyprus (14.1%). On the other hand, obese men registered the lowest shares in Romania (11.1%), Italy (12.9%), the Netherlands (13.2%) and France (14.3%).

The highest proportions of women considered to be obese were recorded in Estonia (23.6%) Latvia (25.7%), Ireland (26.0%) and Malta (26.7%), while for obese men the highest shares were found in Croatia (23.7%), Ireland (25.7%), Hungary (25.8%) and Malta (30.6%) (see Figures1 and2).

There was no systematic difference between the sexes as regards the share of obese women and men in 2019. In 17EU Member States for which data are available, a higher proportion of men (compared with women) were obese, with Malta (3.9percentage points - pp), Czechia and Luxembourg (3.8pp) presenting the highest differences. By contrast, a higher proportion of women were obese in 10 Member States with Latvia (6.1pp), Estonia (3.9pp) and Lithuania (3.5pp) presenting the largest differences. In Germany, Greece and Sweden the share of obese women and men was almost the same (below 0.2pp) (see Figures 1 and 2).

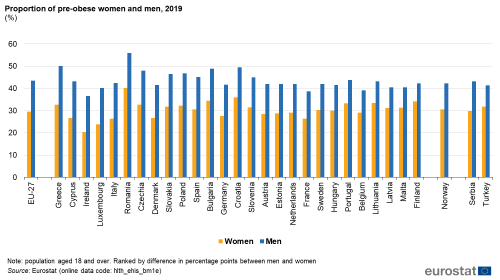

A higher proportion of men (than women) were pre-obese in each EU Member State

There was a much clearer picture as regards the differences between the sexes in relation to the share of the male and female populations that were considered to be pre-obese.In 2019, across all EU Member States, the proportion of pre-obese men was consistently higher than the one for women, with differences ranging from 8.1 pp in Finland to 17.5 pp in Greece (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Proportion of pre-obese women and men, 2019

(%)

Source:Eurostat

(hlth_ehis_bm1e)Obesity by age group

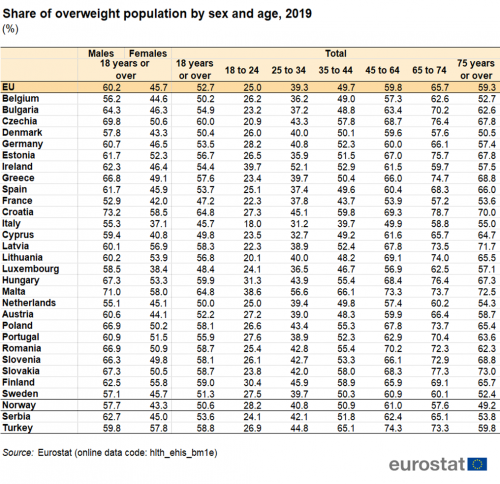

The share of the population that was overweight generally increased with age

Table1 presents the proportion of the population that was overweight in 2019, by age groups. There was a marked increase in the proportion of population that was overweight with increasing age. The age group '18to24' presented the lowest shares of overweight population (25.0%), while the 65to74 had the highest shares (65.7%). Exceptions to this pattern were found in Denmark, Ireland and Sweden (as well as Norway and Turkey) where the percentage of overweight was highest in the 54to64 age group.

Table 1: Share of overweight population by sex and age, 2019

(%)

Source:Eurostat

(hlth_ehis_bm1e)Education level and overweight

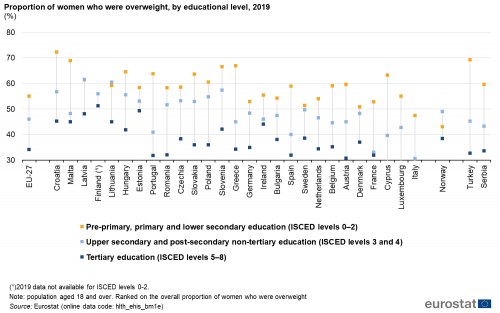

As the education level of women rose, the proportion considered as being overweight fell

Figures4 and 5 show the proportion of women and men who were overweight in 2019, according to their educational attainment level. The proportion of women who were overweight was lower among those with higher levels of educational attainment (see Figure4) and this pattern held in all EU Member States. Indeed, the difference between overweight women with a tertiary education and those with no more than a lower secondary level of education was at least 32pp in Portugal (32.0pp), Greece (32.6pp) and France (34.7pp).

Figure 4: Proportion of women who were overweight, by educational level, 2019

(%)

Source:Eurostat

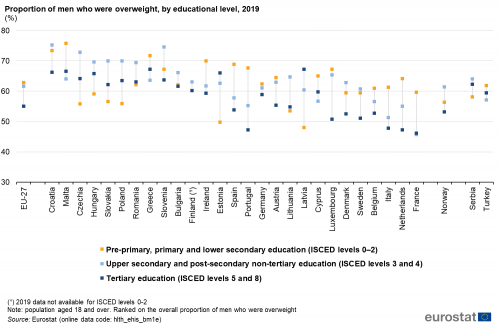

(hlth_ehis_bm1e)For men, there was no clear cut pattern linking educational attainment levels and being overweight (see Figure5). The differences in the proportion of men who were overweight according to educational attainment were generally much smaller than for women. In 13EU Member States, the highest proportion of men who were overweight was recorded among those with no more than a lower secondary level of educational attainment, while only in 2countries - Estonia and Latvia - the highest proportion of overweight men was recorded among those with a tertiary level of education.

Figure 5: Proportion of men who were overweight, by educational level, 2019

(%)

Source:Eurostat

(hlth_ehis_bm1e)Data sources

Health status

The European health interview survey (EHIS) is the source of information for this article. It aims to provide harmonised statistics across the EU Member States in relation to the respondents health status, lifestyle (health determinants) and their use of healthcare services. This source is documented in more detail in this background article which provides information on the scope of the data, its legal basis, the methodology employed, as well as related concepts and definitions.

The third wave of the EHIS was conducted in all EU Member States during 20182020 according to the European Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No. 255/2018. The data presented here are the results for individual EU Member States from this third wave of the survey.

Body mass index

The body mass index (BMI) is a measure of a persons weight relative to their height that links fairly well with body fat. The BMI is accepted as the most useful measure of obesity for adults (those aged 18 years and over) when only weight and height data are available. It is calculated as a persons weight (in kilograms) divided by the square of his or her height (in metres). BMI = weight (kg) / height (m)

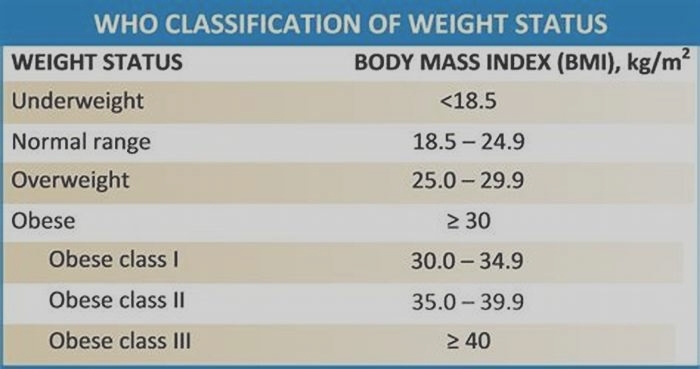

The following subdivision (according to the WHO) is used to classify results for the BMI:

- < 18.50: underweight;

- 18.50 < 25.00: normal range;

- >=25.00: overweight;

- >= 30.00: obese.

The analysis of people who are overweight or obese by educational level is based upon the International standard classification of education (ISCED), 1997 version, and refers to:

- pre-primary, primary and lower secondary education (ISCED levels 02);

- upper secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education (ISCED levels 3 and 4);

- tertiary education (ISCED levels 58).

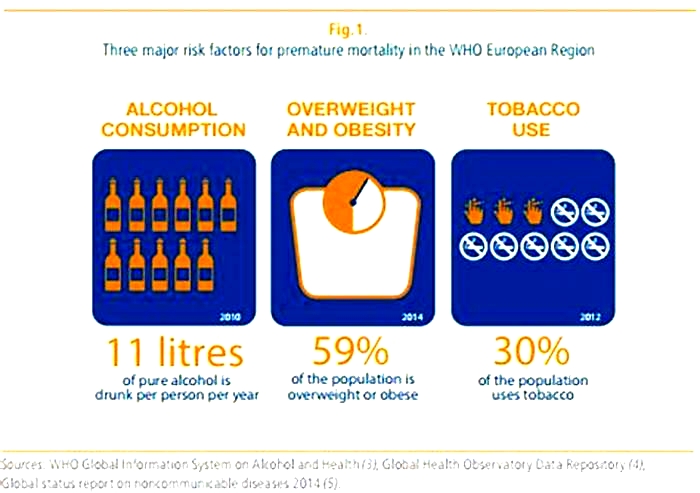

The EHIS measures a range of indicators in relation to health determinants aside from the BMI, such as the consumption of fruit and vegetables, tobacco and alcohol, as well physical activity.

Context

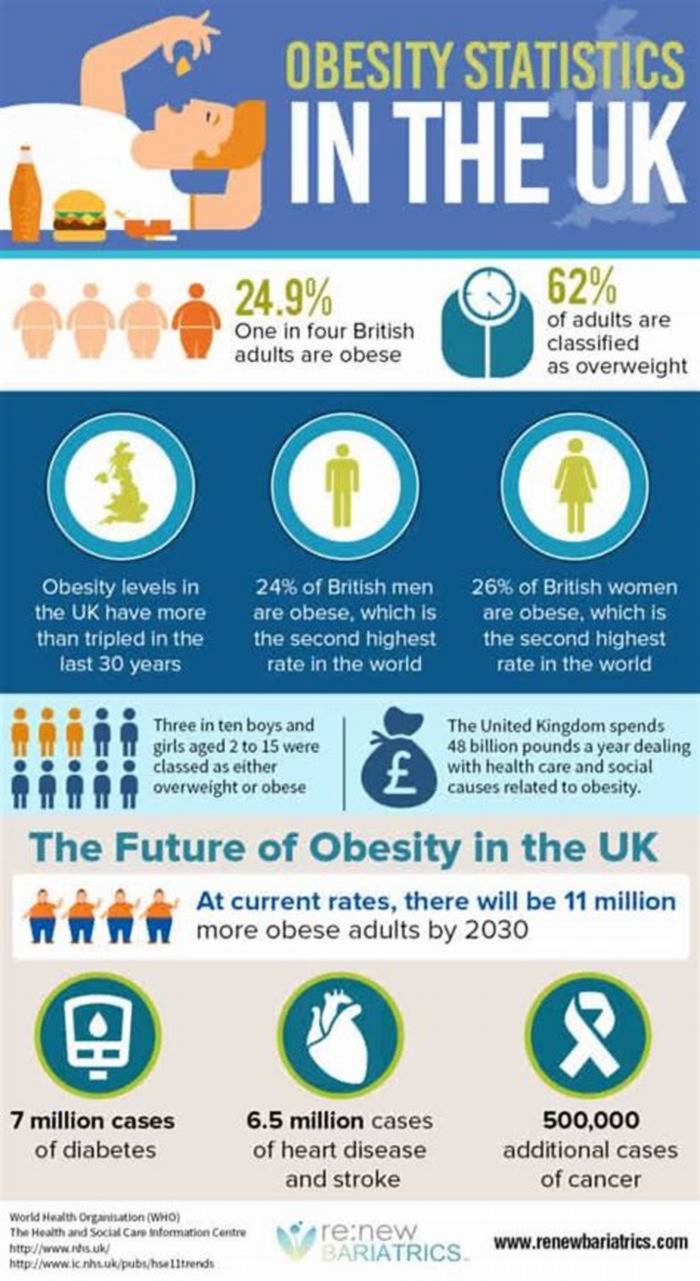

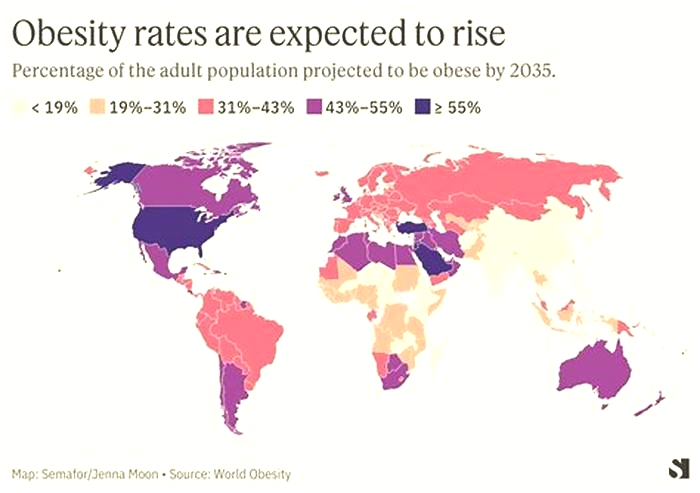

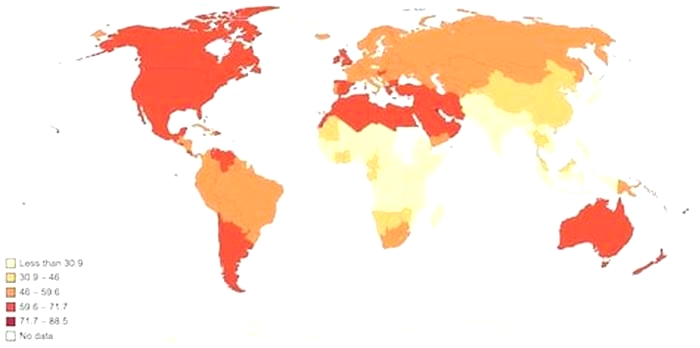

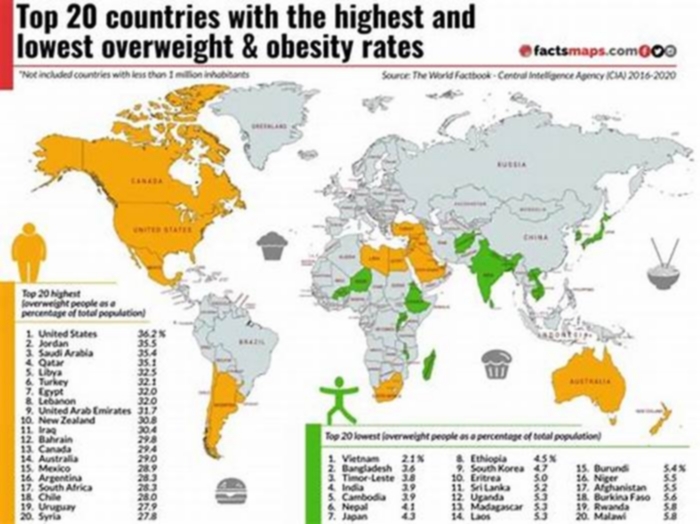

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), worldwide obesity has nearly tripled since 1975. In 2016, 39% of adults aged 18 years and over were overweight and 13% were obese.

Indeed, the number of overweight and obese persons has been growing in recent years and many people find it increasingly difficult to maintain a normal weight in today's largely obesogenic environment. This environment spans from low breastfeeding rates to difficulties in geographically or financially accessing the ingredients of a healthy diet, to a lack of cooking skills, to the abundance and marketing of energy-rich foods, to urban planning choices and lifestyle pressures that often reduce the opportunity for physical activity (both at work or for leisure). While obesity was once considered a problem only for high income countries, there has been a considerable increase in the proportion of people from low- and middle-income countries who are considered to be overweight or obese (in particular in urban areas where people are more prone to a sedentary lifestyle). The malnutrition problem has become more complex as obesity and deficiencies in micronutrients can and do go hand in hand.

Nutrition is the intake of food, considered in relation to the bodys dietary needs. Good nutrition an adequate, well-balanced diet combined with regular physical activity is a cornerstone for good health. Specific recommendations for a healthy diet include: eating more fruit, vegetables, nuts and grains; cutting down on salt, sugar and fats. Poor nutrition can lead to reduced immunity, increased susceptibility to disease, and impaired physical and mental development. Indeed, across the EU, six of the seven largest risk factors for premature death blood pressure, cholesterol, weight, inadequate fruit and vegetable intake, physical inactivity, and alcohol abuse may, at least in part, be linked to how we eat, drink and exercise.

In March 2007, the European Commission established a coherent and comprehensive Community Strategy to address the issues of overweight and obesity, by adopting the White Paper Strategy for Europe on nutrition, overweight, and obesity-related health issues (COM(2007)279 final) focusing on action that can be taken at local, regional, national and European levels to reduce the risks associated with poor nutrition and limited physical exercise, while addressing the issue of inequalities across Member States. An Action Plan on Childhood Obesity was endorsed in 2014 by the members of the High Level Group on Nutrition and Physical Activity (with a reserve by the Netherlands). In the same year, Council Conclusions on Nutrition and Physical Activity were published.

Additional details on the latest EU initiatives on nutrition and physical activity aiming to promotion and disease prevention are available here.

Obesity in Malta

Overview of obesity in Malta

Obesity in Malta is a contemporary health issue. This problem is connected to several other illnesses and economic costs for the government. The causes for Malta's obesity are various and one of the leading aspects is physical inactivity.

Malta's authorities declare that obesity is one of the major preventable causes of other illnesses and finally, leading to an earlier death. In 2014, with the publication of the Eurostat statistics, Malta's obesity problem caught the national, as well as international attention intensively. In the same year, Malta's Parliamentary Secretary for Health, Chris Fearne, announced that the government is committed to tackle the prevailing obesity problem in Malta.[1]

Malta appears to be the most obese country within the European Union - according to Eurostat and the World Health Organization.[2][3]

With 26% - meaning one out of four adults - being obese, Malta is far ahead on the obesity scale, comparable to other EU countries.[3] For children, the situation is worse in Malta, as 40% of all children are obese there. The prevalence of obesity has increased from 23% in 2002 to 25% in 2015.[4]

In general, Eurostat bases its obesity observation on a BMI calculation. In regard to this method, the definition of obesity is that a person needs to have a higher BMI of 30 in order to be categorized as obese.[5]

Important findings of the Eurostat statistics included the systematic difference between men and women concerning the obesity level. The proportion of men being obese, with 28.1%, was much higher than that of women in Malta, with 23.9%.[3] The age also plays an important role in Malta's obesity problem. Whereas only one young adult person out of 10 is considered to be obese in Malta (12%), one out of three older persons in Malta (33.6%) is categorized as obese.[3]

Education plays a certain role in Malta's obesity problem. In almost every EU member state, the share of obesity decreases with education level. 30.3% of Malta's obese population come from a low education level, and only 15.8% of people with a high education level were being classified as obese.[3]

Effects[edit]

Obesity tends to lead to a number of non-communicable diseases and impacts individuals through a lower quality and length of life. The mental effects of obesity should not be ignored either: depression, discrimination and lower educational attainment are psychological aspects related to the physical negative consequences.[4] Regarding the subsequent illnesses of obesity, the chances of being affected by diabetes type two, high blood pressure, heart diseases, a stroke, as well as some forms of cancer are way higher.[6] Furthermore, there exists evidence that obesity and mortality risks are positively related.[7] Malta, contradictory to this statement, has one of the highest life expectancies within Europe.[8] Its life expectancy at birth was 81.9 years in 2015 and therefore above the EU average of 80.6 years.[9] Nevertheless, cardiovascular diseases remain the leading cause in Malta for men and women. Additionally, death rates from ischaemic heart disease in Malta remain above the EU average, but have shown a relatively consistent downward trend. More than a quarter of all deaths from ischaemic heart disease were premature, occurring in people aged under 75.[9]

Costs for the Government[edit]

But not only the health and quality of life of individuals is negatively influenced by obesity, but the costs associated with obesity are also weighing on the shoulders of several stakeholders, inter alia the government and the society at large. Based on the 2015 EHIS results, the cost of obesity in Malta has been estimated at 36.3 million euro. 23.8 million euros are thereby direct costs, divided into primary care, specialist care, hospital care, cost of allied healthcare professionals, pharmaceutical care, weight loss interventions and public interventions. The indirect costs, amounted to 12.5 million euro, consist of absenteeism, presenteeism, government subsidies, forgone earnings and forgone taxes.[4] Different scholars point out a figure of 23.7 million euro for overweight and obesity in Malta, including herewith hospital costs and the cost of visits to general practitioners and specialists.[10] Furthermore, the inability to stop the growing levels of obesity will probably result in a loss up to 90,000 hours of work for Malta due to the connected health complications. Besides, it is also estimated that, if the rising percentages of obesity will not be stopped, the costs of obesity will rise to 41.4 million euro which is equal to 110 euro per capita. In the long term, the figure could even rise to 46.5 million euros by 2050.[11]

Physical Inactivity[edit]

For decades, Malta has been sheltered from the influence of other cultures, but with its entry into the European Union and the growing globalization, Malta became easier to access. This aspect, in turn, led to more trade relations, enhancing its tourism and economic opportunities. Moreover, its culture and lifestyle were equally influenced. It is argued that it is exactly this change of Malta's traditional Mediterranean diet to a high-fat and high-sugar fast food nutrition which is favored by many Western European countries and the United States.[12] When regarding the causes of obesity in general, the major reasons for weight gains include diminished physical activity, high-fat diets and inadequate adjustments of energy intakes.[13][14] On the one hand, it is Malta's extremely westernized diet - which the Mediterranean genes cannot adopt to quickly.[15] On the other hand, it is Malta's lack of physical activity, affecting its obesity rate.

Taking the aspect of physical activity more detailed into account, there can be different layers identified for impacting the physical activity of a country. There exist natural,- built,- and social environment factors, as well as individual determinants.[16]

One factor influencing Malta's physical inactivity plays its built environment, meaning its urban design and its infrastructure. Infrastructure which is designed to encourage physical activity, such as the construction of bike lanes, diminishes obesity.[17] Malta has the highest motorisation rate among any region from one of the Member States that joined the EU in 2004 or more recently. Following this argument, its motorisation rate consisted of 592 passenger cars per thousand inhabitants in 2012.[18] There are usual smaller EU countries which are having the highest motorisation rates: Luxembourg makes the first place with 661 passenger cars per 1000 inhabitants, whereas Malta follows directly with 634 cars per 1000 inhabitants.[18]

Next to the built environment, it is the social environment which influences the physical activity of a country. In this respect, the income factor is decisive. There exist a definite correlation between physical inactivity and a low level of income.[19] With 11 billion euro, Malta has the lowest GDP ration as country in 2017, compared to the other EU countries. When looking at the GDP per inhabitant (in accordance with the Purchasing Power Standards), Malta belongs with 27,500 euro to the lowest quarter of the EU countries. Luxembourg, with 75,000, is the country with the highest GDP per inhabitant.[20] Malta's comparably low income level explains partly its physical inactivity and its high obesity rate.

The individual determinant includes the education factor. It is a concern that people with a lower education status are more prone to be less physically active, since these groups have less leisure time or poorer access to recreation and sport facilities.[21] With 18.6%, Malta has the highest percentage of all EU countries regarding early leavers from education (aged 1824).[22] Malta's low commitment to exercise is also based on its general low education level.

Remedies[edit]

Especially since 2014, when the statistics about Malta being the most obese country, got published, Malta's government tries actively to tackle to obesity issue. Childhood obesity, in particular, is one of its major concerns: Kindergarten children learn how to prepare healthy foods and shops in schools are allowed to sell only products the Maltese authorities consider as healthy.[23] In general, Malta's government launched several initiatives in order to reduce obesity. One of them is the 'Healthy Weight for Life strategy for 20122020, which aims to establish a society in which healthy lifestyles related to diet and physical activity become the norm and healthy choices are easy and accessible to all.[24] Furthermore, Malta published the "Food and Nutrition Policy and Action Plan for Malta 2015-2020".[25]

References[edit]

- ^ "Government committed to tackle obesity with solid measures - The Malta Independent". www.independent.com.mt. Retrieved 2018-05-18.

- ^ "Nutrition, Physical Activity and Obesity - Malta" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2013. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ a b c d e "Overweight and obesity - BMI statistics - Statistics Explained". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 2018-05-18.

- ^ a b c PricewaterhouseCoopers. "Weighing the costs of obesity". PwC. Retrieved 2018-05-18.

- ^ Ltd, Allied Newspapers. "40% of Maltese children overweight or obese". Times of Malta. Retrieved 2018-05-18.

- ^ Javier), Varo, J.J. (Jos; ngel), Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A. (Miguel; de, Irala, J. (Jokin); (J.), Kearney, J.; (M.J.), Gibney, M.J.; Alfredo), Martinez, J.A. (Jos (2003). "Distribution and determinants of sedentary lifestyles in the European Union". International Journal of Epidemiology. ISSN0300-5771.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Abdullah, Asnawi; Wolfe, Rory; Stoelwinder, Johannes U.; de Courten, Maximilian; Stevenson, Christopher; Walls, Helen L.; Peeters, Anna (August 2011). "The number of years lived with obesity and the risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality". International Journal of Epidemiology. 40 (4): 985996. doi:10.1093/ije/dyr018. ISSN1464-3685. PMID21357186.

- ^ "Life expectancy in Malta is higher than European average - TVM News". TVM English. Retrieved 2018-05-18.

- ^ a b "Malta: Country Health Profile 2017 - en - OECD". www.oecd.org. Retrieved 2018-05-18.

- ^ Cuschieri, Sarah; Vassallo, Josanne; Calleja, Neville; Camilleri, Ryan; Borg Axisa, Ayrton; Bonnici, Gary; Zhang, Yimeng; Pace, Nikolai; Mamo, Julian (2016-10-09). "Cuschieri et al-2016-Obesity Science & Practice".

- ^ Ltd, Allied Newspapers. "Rising levels of obesity may soon hit the economy". Times of Malta. Retrieved 2018-05-19.

- ^ "Why Are The Maltese So Fat?". International Business Times. 2011-11-26. Retrieved 2018-05-19.

- ^ Whitaker, Robert C.; Wright, Jeffrey A.; Pepe, Margaret S.; Seidel, Kristy D.; Dietz, William H. (1997-09-25). "Predicting Obesity in Young Adulthood from Childhood and Parental Obesity". New England Journal of Medicine. 337 (13): 869873. doi:10.1056/nejm199709253371301. ISSN0028-4793. PMID9302300.

- ^ Attard, Manuel (2010). "Assessment of the Nutritional Knowledge of Maltese Adults" (PDF). Masters Thesis: 12.

- ^ Wells, Jonathan C.K. (2012-03-02). "Obesity as malnutrition: The role of capitalism in the obesity global epidemic". American Journal of Human Biology. 24 (3): 261276. doi:10.1002/ajhb.22253. ISSN1042-0533. PMID22383142. S2CID21400866.

- ^ Graham, H.; White, P.C.L. (2016-12-01). "Social determinants and lifestyles: integrating environmental and public health perspectives". Public Health. 141: 270278. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2016.09.019. ISSN0033-3506. PMID27814893.

- ^ Tucker, Patricia; Irwin, Jennifer D.; Gilliland, Jason; He, Meizi; Larsen, Kristian; Hess, Paul (March 2009). "Environmental influences on physical activity levels in youth". Health & Place. 15 (1): 357363. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.07.001. ISSN1353-8292. PMID18706850.

- ^ a b "Transport - Statistics Explained". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 2018-05-20.

- ^ Jin, Yichen; Jones-Smith, Jessica C. (2015-02-12). "Associations Between Family Income and Children's Physical Fitness and Obesity in California, 20102012". Preventing Chronic Disease. 12: E17. doi:10.5888/pcd12.140392. ISSN1545-1151. PMC4329950. PMID25674676.

- ^ publisher. "Data by country - EU comparison 2018: Germany and the other Member States - Federal Statistical Office (Destatis)". www.destatis.de. Retrieved 2018-05-20.

- ^ Ford, E. S.; Merritt, R. K.; Heath, G. W.; Powell, K. E.; Washburn, R. A.; Kriska, A.; Haile, G. (1991-06-15). "Physical activity behaviors in lower and higher socioeconomic status populations". American Journal of Epidemiology. 133 (12): 12461256. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115836. ISSN0002-9262. PMID2063832.

- ^ publisher. "Data by country - EU comparison 2018: Germany and the other Member States - Federal Statistical Office (Destatis)". www.destatis.de. Retrieved 2018-05-20.

- ^ "Malta's battle of the bulge". POLITICO. 2017-04-10. Retrieved 2018-05-20.

- ^ "Malta launches obesity strategy". www.euro.who.int. 2012-05-01. Retrieved 2018-05-20.

- ^ "Policy - Food and Nutrition Policy and Action Plan for Malta 2015-2020 | Global database on the Implementation of Nutrition Action (GINA)". extranet.who.int. Retrieved 2018-05-20.