Does the UK have an obesity problem

Overview - Obesity

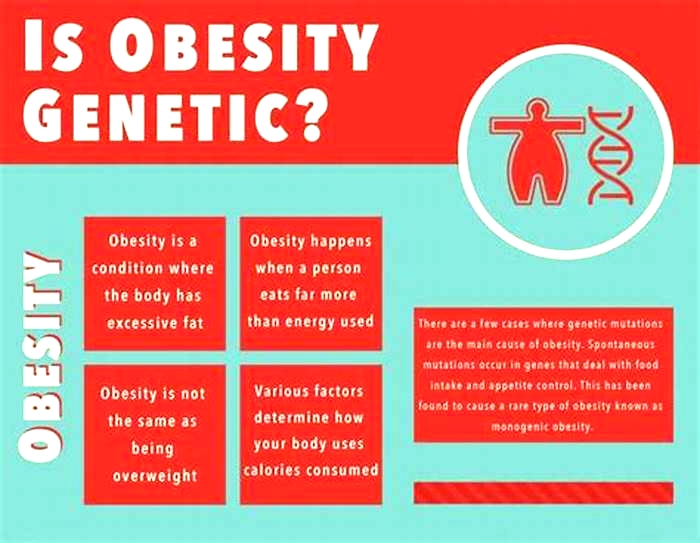

The term obese describesa personwho has excess body fat.

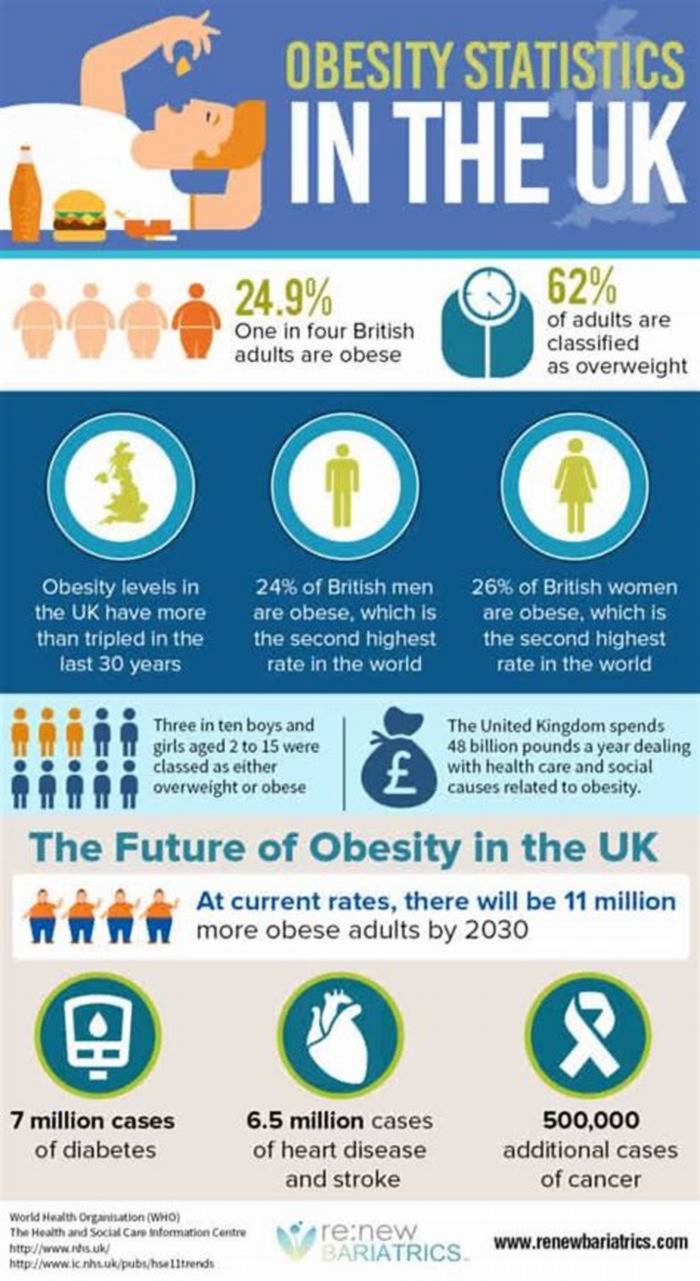

In the UK it's estimated thataround 1 in every 4 adults and around 1 in every 5 children aged 10 to 11 are living with obesity.

How to tell if you're living with obesity

The most widely used method to check if you're a healthy weight is body mass index (BMI).

Body mass index (BMI)

BMI is a measure of whether you're a healthy weight for your height. You can use the NHS BMI healthy weight calculator to find out your BMI.

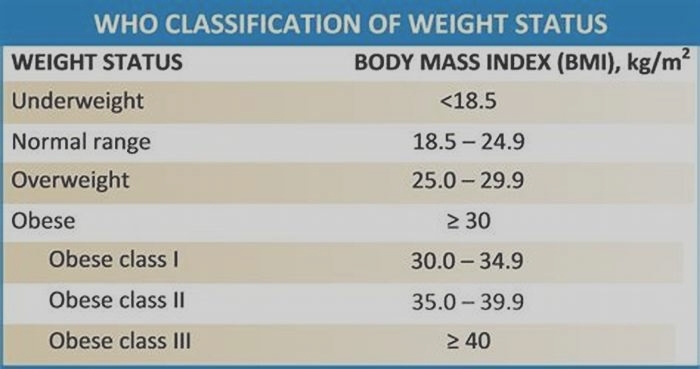

For most adults, if your BMI is:

- below 18.5 you're in the underweight range

- 18.5 to 24.9 you're in the healthy weight range

- 25 to 29.9 you're in the overweight range

- 30 to 39.9 you're in the obese range

- 40 or above you're in the severely obese range

If you have an Asian, Chinese, Middle Eastern, Black African or African-Caribbean family background you'll need to use a lower BMI score to measure overweight and obesity:

- 23 to 27.4 you're in the overweight range

- 27.5 or above you're in the obese range

BMI score has some limitations because it measures whether a person is carrying too much weight but not too much fat. For example, people who are very muscular, like professional sportspeople, can have a high BMI without much fat.

But for most people, BMI is a useful indication of whether they're a healthy weight.

Waist to height ratio

Another measure of excess fat is waist to height ratio, which can be used as an additional measure in adults who have a BMI under 35.

To calculate your waist to height ratio:

- Find the middle point between your lowest rib and your hip bone. This should be roughly level with your belly button.

- Wrap the tape measure around this middle point, breathing naturally and not holding your tummy in.

- Take your measurement and divide it by your height, measured in the same units (for example, centimetres or inches).

For example, if your waist is 80cm and you are 160cm tall, you would calculate your result like this: 80 divided by 160, which equals 0.5.

A waist to height ratio of 0.5 or higher means you may have increased health risks.

How to measure your waist

This video explains how to measure your waist so you can calculate your waist to height ratio.

Media last reviewed: 10 November 2023 Media review due: 10 November 2026

Risks of living with obesity

Obesity is a serious health concern that increases the risk of many other health conditions.

These include:

Living with overweight and obesity can also affect your quality of life and contribute to mental health problems, such as depression,andcan also affect self-esteem.

Causes of obesity

Obesity is a complex issue with many causes. Obesity and overweight is caused when extra calories,particularly those from foods high in fat and sugar, are stored in the body as fat.

Obesity is an increasingly common problem because the environment we live in makes it difficult for many people to eat healthily and do enough physical activity.

Genetics can also be a cause of obesity for some people. Your genes can affect how your body uses food and stores fat.

There are also some underlying health conditions that can occasionally contribute to weight gain, such as an underactive thyroid gland (hypothyroidism), although these types of conditions do not usually cause weight problems if they're effectively controlled with medicines.

Some medicines can also make people more likely to put on weight, including steroids and some medicines for high blood pressure, diabetes or mental health conditions.

Treating obesity

The best way to treat obesity is to eat a healthy reduced-calorie diet and exercise regularly.

To do this, you can:

- eat a balanced calorie-controlled diet as recommended by a GP or weight loss management health professional (such as a dietitian)

- take up activities such as fast walking, jogging,swimming or tennis for 150 to 300minutes (2.5 to 5 hours) a week

You may benefit from joining a local weight management programme with group meetings or online support. Your GP can tell you about these.

You may also benefit from receiving support and counselling from a trained healthcare professional to help you better understand your relationship with food and develop different eating habits.

If you're living with obesity and lifestyle and behavioural changes alone do not help you lose weight, a medicine called orlistat may be recommended.

If taken correctly, this medicine works by reducing the amount of fat you absorb during digestion. Your GP will know whether orlistat is suitable for you.

A specialist may prescribe other medicines called liraglutide or semaglutide. They work by making you feel fuller and less hungry.

For some people living with obesity, a specialist may recommendweight loss surgery.

Other obesity-related problems

Living with obesity cancause anumber of further problems, including difficulties with daily activities and serious health conditions.

Day-to-day problems related to obesity include:

- breathlessness

- increased sweating

- snoring

- difficultydoingphysical activity

- often feeling very tired

- joint and back pain

- low confidence and self-esteem

- feeling isolated

The psychological problems associated with living with obesity can also affect your relationships with family and friends, and may lead to depression.

Serious health conditions

Living with obesity can also increase your risk of developing many potentially serioushealth conditions, including:

- type 2 diabetes

- high blood pressure

- high cholesterolandatherosclerosis(where fatty deposits narrow your arteries), which can lead to coronary heart disease and stroke

- asthma

- metabolic syndrome, a combination of diabetes, high blood pressure and obesity

- several types of cancer, including bowel cancer, breast cancer and womb cancer

- gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD), where stomach acid leaks out of the stomach and into the gullet

- gallstones

- reduced fertility

- osteoarthritis, a condition involving pain and stiffness in your joints

- sleep apnoea, a condition that causes interrupted breathing during sleep, which can lead to daytime sleepiness with an increased risk of road traffic accidents, as well as a greater risk of diabetes, high blood pressure and heart disease

- liver disease and kidney disease

- pregnancy complications,such asgestational diabetes orpre-eclampsia, when a woman experiences a potentially dangerous rise in blood pressure during pregnancy

Obesity reduces life expectancy by an average of3 to10 years, depending on how severe it is.

Outlook

Managing a complex issue like obesity can be hard. Losing weight takes time and commitment.

The healthcare professionals involved with your care can provide encouragement and advice about how to mange your weight, build healthy lifestyle habits and maintain weight loss achieved.

Completing a weight management programme, regularly monitoring your weight, setting realistic goals, and involving your friends and family with ways tolose weight can also help.

It's important to remember that losing what seems like a small amount of weight, such as 3% or more of your original body weight, and maintaining this for life, can significantly reduce your risk of developing obesity-related complications like diabetes and heart disease.

Social care and support guide

If you:

- need help with day-to-day living because of illness or disability

- care for someone regularly because they're ill, disabled or because of their age (including family members)

Our guide to care and support explains your options and where you can get support.

Couch to 5K

If it's been a long time since you did any exercise, you should check out the Couch to 5K running plan.

It consists of podcastsdelivered over the course of 9 weeks and has been specifically designed forabsolute beginners.

To begin with,you start running forshort periods of time, and as the plan progresses, gradually increase the amount.

Atthe end of the 9 weeks, you should be able to run for 30 minutes non-stop, which for most people is around 5 kilometres (3.1 miles).

Page last reviewed: 15 February 2023 Next review due: 15 February 2026

Why are Brits the fattest in Western Europe?

Paul Gately, Professor of Exercise and Obesity at Leeds Beckett University, believes fundamental cultural differences partly explain why the UKs prevalence of obesity and overweight is comparatively high. We approach food and mealtimes, particularly lunchtime, differently to other parts of Western Europe, he says.

Many countries across Western Europe have a much stronger and more prominent food culture than we do, Professor Gately explains. Meals are an important and distinctive part of the day that can run for several hours in countries like France, Italy and Spain. Its a time for sitting down and conversing, and focusing on friends and family. But in the UK meals are not so socially and culturally embedded.

Rather than break away from work to eat a proper lunch, still a common practice in many parts of Western Europe, we tend to grab a sandwich to eat at our desks.

In UK culture we often eat on the run, and then become peckish an hour or two later, so we eat again, says Professor Gately. Were constantly grazing throughout the day, with almost no recognition of the eating episodes, so they almost blur into one.

Our inclination to snack is confirmed by Global Obesity Federation figures, which show British adults consume more sweet and salty snacks than those in many other European countries. In 2016, we ate almost 700g of sweet and savoury snacks per month or 20 x 35g servings. This is less than in Ireland (770g per month), but more than in the Netherlands (625g) and significantly more than in Italy (192g), for example.

Part of the reason we reach for snacks instead of taking time for a proper meal is the importance we place on productivity and working long hours, says Professor Ivo Vlaev, a behavioural scientist at Warwick Business School and an advisor to the government on health issues. Snacking often happens when youre in the workplace and you eat to keep yourself working, he says. And were one of the hardest working nations in Europe, obsessed with productivity, so thats one reason for the continuous snacking.

Further evidence of the UKs snacking culture is our food-to-go market, one of the fastest-growing food sectors in recent years (although the trend has been impacted by Covid-19 and the shift to homeworking during lockdown). This means we are continually bombarded with visual cues encouraging us to snack, to the extent theyre difficult to resist, Professor Vlaev believes.

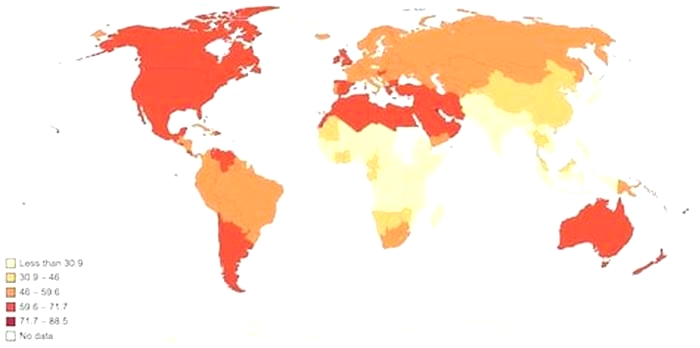

Obesity

Obesity is a major public health problem, both internationally and within the UK. Being overweight or obese is associated with an increased risk of several common diseases including diabetes, cardiovascular disease and some cancers. Evidence also suggests that obesity is associated with an increased risk of severe illness and death from Covid-19.

In July 2020, the government published Tackling obesity: empowering adults and children to live healthier lives, which outlined policies to support healthy eating and expand NHS weight management services. In September 2022, the government released a plan on the non-promotion of food and drinks high in fat, salt, or sugar by restricting volume offers like buy one get one free. However, the implementation of this plan has been delayed until October 2025.

Childhood obesity is similarly a major public health problem. Children who have obesity are at greater risk of high blood pressure, high cholesterol, diabetes and other long-term conditions that last into adulthood. In 2016, the government launched Childhood obesity: a plan for action, which set out a number of actions primarily focused on reducing sugar consumption and increasing physical activity among children. In June 2018, an update to the action plan was published, setting a national ambition to "halve childhood obesity and reduce the gap in obesity between children from the most and least deprived areas by 2030".

EditHow has the proportion of adults who are overweight and obese changed over time?

ChartThe Health Survey for England collects height and weight measurements from a representative sample of the general population, which are used to calculate body mass index (BMI) statistics. This measure allows us to estimate the proportion of the population who are overweight (BMI 25kg/m2 to <30kg/m2) or obese (30kg/m2).

This indicator shows trends in obesity and overweight in adults from 1993 to 2021. The prevalence of obesity increased sharply between 1993 and 2001, followed by a slower rate of increase in the following years. In 2021, 38% of the adult population were overweight and 26% were obese. The proportion of adults who were underweight is not reported for 2021 because certain methodological factors make those estimates unlikely to be accurate. See About this data for more information.

Comparing men and women in 2021, 26% of all adult women were obese and 32% were overweight, whereas 25% of adult men were obese and 43% were overweight (data on differences in gender not shown). Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, data was not collected in 2020 and no publication was released.

EditHow has the proportion of children aged 10-11 who are overweight and obese changed over time?

ChartThe National Child Measurement Programme (NCMP) collects the height and weight measurements of over one million children in Reception (aged 45 years) and Year 6 (aged 1011 years) in mainstream state schools in England.

Between 2006/07 and 2019/20, the prevalence of obesity had increased from 17.5% to 21%. In 2020/21 there was a sizeable increase in the prevalence of obesity in children. One in four children (26%) in Year 6 were obese or severely obese in the 2020/21 school year, up from one in five in 2019/20 (21%). One in seven children (14%) in Reception were obese or severely obese in the 2020/21 school year, up from one in 10 in 2019/20 (10%) (data not shown). In 2021/22, the prevalence of obesity in children decreased but remained higher than the estimate in the pre-pandemic period. For Year 6 children, the prevalence decreased to 23%, and for children in Reception it returned to 10%.

Between 2006/07 and 2021/22, the proportion of children with a healthy weight decreased by 6 percentage points for those in Year 6 while no significant change was recorded for those in Reception. The proportion of children who were overweight or underweight has remained relatively stable over this time period.

When looking at the prevalence of obesity by ethnicity for children in Year 6 in 2021/22, children described as Chinese (18%) had a lower rate of obesity compared to the average (23%). However, children described as being Mixed, Asian and Black had a higher rate of obesity than the average; 25%, 28% and 33% respectively.

EditHow does the prevalence of obesity in children vary by deprivation?

ChartThere is a strong association between deprivation and obesity in children. This is in line with recently published evidence that states that obesity levels in children are likely to be higher in areas where low income families reside. In 2021/22, the prevalence of obesity in children in the most deprived areas was more than double the value in the least deprived areas. This is true both for children in Reception and in Year 6.

In 2020/21, the prevalence of obesity in children increased significantly. Between 2019/20 and 2020/21, the prevalence of obesity in Reception-aged children increased from 13% to 20% in the most deprived areas; in the least deprived areas this increased from 7% to 9%. Similarly, the prevalence of obesity in children in Year 6 increased from 22% to 32% in the most deprived areas, and from 13% to 16% in the least deprived areas. The increase in prevalence was disproportionately higher for children in the most deprived areas.

In 2021/22, the prevalence of obesity returned closer to pre-pandemic levels particularly for Reception-aged children, while for Year 6 children the level of obesity remained higher than in 2019/20. The prevalence of obesity for Year 6 children from the most deprived areas was 3 percentage points higher in 2021/22 than in 2019/20, at 30% in 2021/22, double the prevalence recorded for similar-aged children from the least deprived areas (15%) in that year. In 2021/22, the prevalence of obesity in Reception-aged children in the most deprived areas was 13%, and 7% for Reception-aged children from the least deprived areas.

The governmentsChildhood obesity: a plan for action: Chapter 2had set a national ambition to significantly reduce the gap in obesity between children from the most and least deprived areas by 2030. However, between 2006/07 and 2021/22, the gap in obesity prevalence for children increased by 2.2 percentage points for 45-year-olds and 6.7 percentage points for 1011-year-olds.